I walk into the closet and sigh. I really don’t want to do this. I load a new clip into FBI Agent Saga Anderson’s gun. I double-check my shoebox of spare batteries and bandages, even though I already know what’s in there. I have to do it. It’s time. I square my shoulders and look into the mop bucket puddle that will transport me to become my least favorite part of Alan Wake 2—Alan Wake.

Full spoilers ahead for Alan Wake and Alan Wake 2.

He Was Born in the Darkness, Molded By It

I had to get to the Tower, Alan says to himself. Again. And again.

While writing the opening paragraphs of this op-ed, I felt I sounded just like Alan’s morose, determined murmurings from throughout the game. In the 15+ hours I played of Alan Wake 2, I felt like I heard him say “I had to ____” approximately 1,754 times. Everything with Alan is such a thing. He has to get to the Tower. He has to write a new chapter. He has to envision his story in a new way. Ok, man, then DO IT. Why do I gotta hold your hand every step of the way?

Alan Wake is impressive, I suppose, in that he reminds me of real life people I’ve known. People who say they want to get better, and then don’t. Who say they care about evolving, but don’t do the work. Who say they want something they’ve never had, but aren’t willing to do what they’ve never done before to get it.

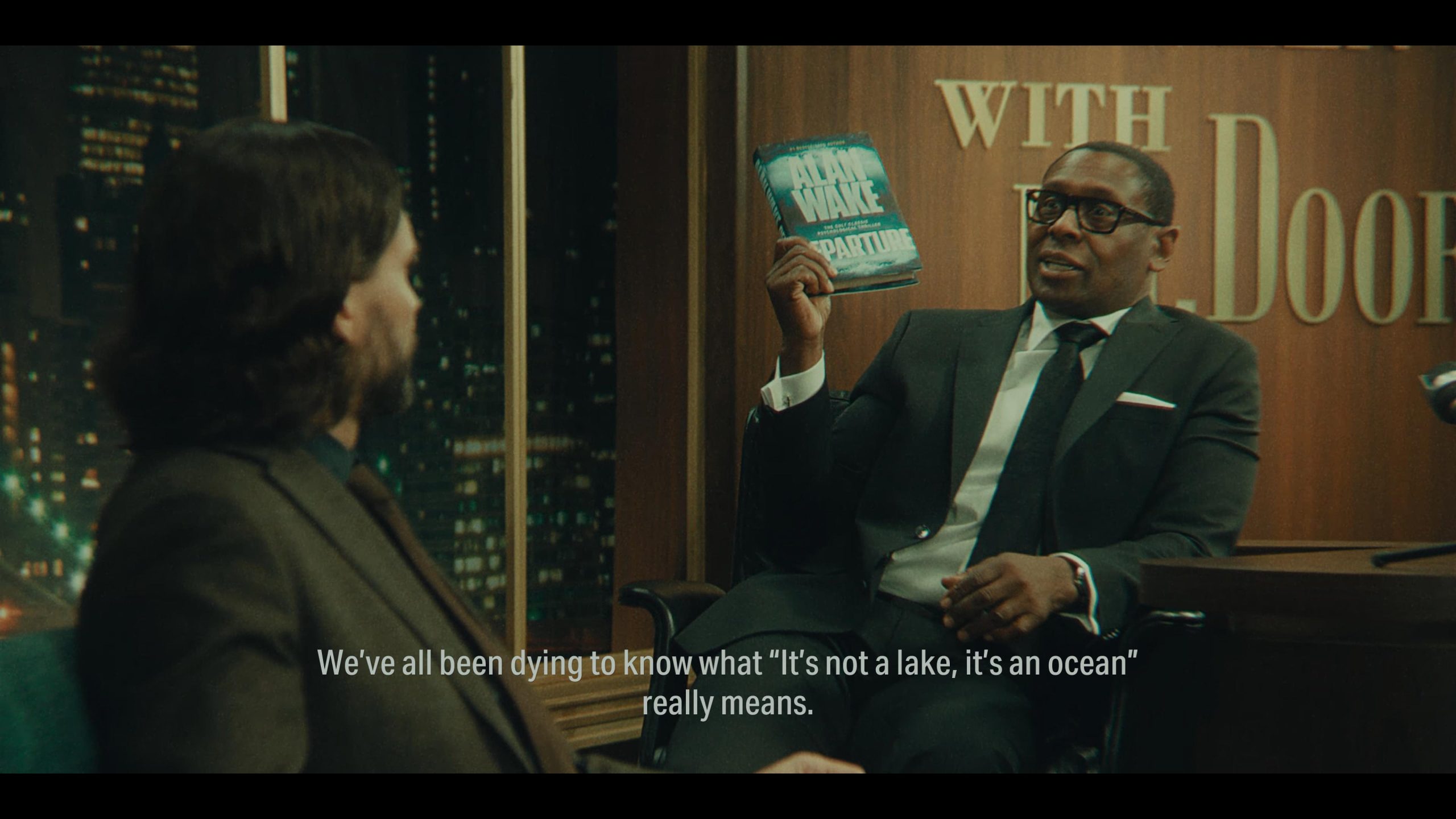

Alan continually lets his fears, anxieties, and ego rule his reality. In his alternate universe, he’s repeatedly the featured guest on a popular talk show. He goes through an epic rock musical where he sees giant versions of himself dancing, the star of the show. Even Alan’s shadowy enemies in the Dark Place (the alternate universe akin to the Upside Down in Stranger Things) can only say one word over and over again—his own name: “Wake!”

When the Devil/Scratch tries to take over the real world through Alan, his “happy place” is a town full of people over-adulating Alan and his new book. To quote Mean Girls’ Regina George, “Like, why are you so obsessed with me?” Alan wants to have people obsessed with him. And that’s not a good look.

As an aspiring novelist and a person who has dealt with depression and anxiety for years, I can see where Alan is coming from. I think Remedy has done a good job of articulating a realistic representation of who that guy could be. I know it’s hard to escape that. But I would argue that Alan consistently embraces the worst parts of himself.

Even the thing that pushes Alan out of his loop is not a positive emotion—it’s guilt. When he learns that his actions and/or his alter-ego has driven wife Alice to suicide, only then is he able to change his patterns. Why is it that only such an awful thing compels Alan to free himself? Because, in a way, I think he likes it. The pain gives him (artistic) purpose. Let me quote Alfred Hitchock’s seminal film, Psycho (1960):

“Norman Bates: No one really runs away from anything. It’s like a private trap that holds us in like a prison. You know what I think? I think that we’re all in our private traps, clamped in them, and none of us can ever get out. We scratch and we claw, but only at the air, only at each other, and for all of it, we never budge an inch.

Marion Crane: Sometimes, we deliberately step into those traps.

Norman Bates: I was born into mine. I don’t mind it anymore.

Marion Crane: Oh, but you should. You should mind it.

Norman Bates: Oh, I do… [laughs] But I say I don’t.”

Alan isn’t just trapped in the Dark Place—he is the Dark Place. And there’s a part of him that prefers it that way. It’s easier than admitting that he is the problem, and that it is within his power to get better.

When players first meet Alan in Alan Wake (2010), he’s not a good guy. He’s an alcoholic, verbally abusive writer who blames everyone else for his problems. His wife Alice is already putting up with a lot of shit. And sure, Alan saves her at the end of that game by sacrificing himself, but maybe if he hadn’t been such a raging asshole to begin with, they would never have gone to Cauldron Lake on their ill-fated vacation. Alan is representative of many self-important artists and/or men who believe that they are entitled to bring everyone around down with them.

Don’t Send a Man To Do a Woman’s Job

Let me be clear that I really enjoyed Alan Wake 2 and that it will surely be on my top 10 Game of the Year list. I rarely play horror games because I am a huge scaredy cat, but fellow Punished Backlog writer Clint Morrison Jr. did such a wonderful job reviewing the game that I had to check it out. It’s a compliment to Remedy that I loved the game so much despite how annoyed I was with the titular character.

My frustration with Alan hit two peaks in the last hour of the game, both as a result of moments with female characters. Let’s start with the first.

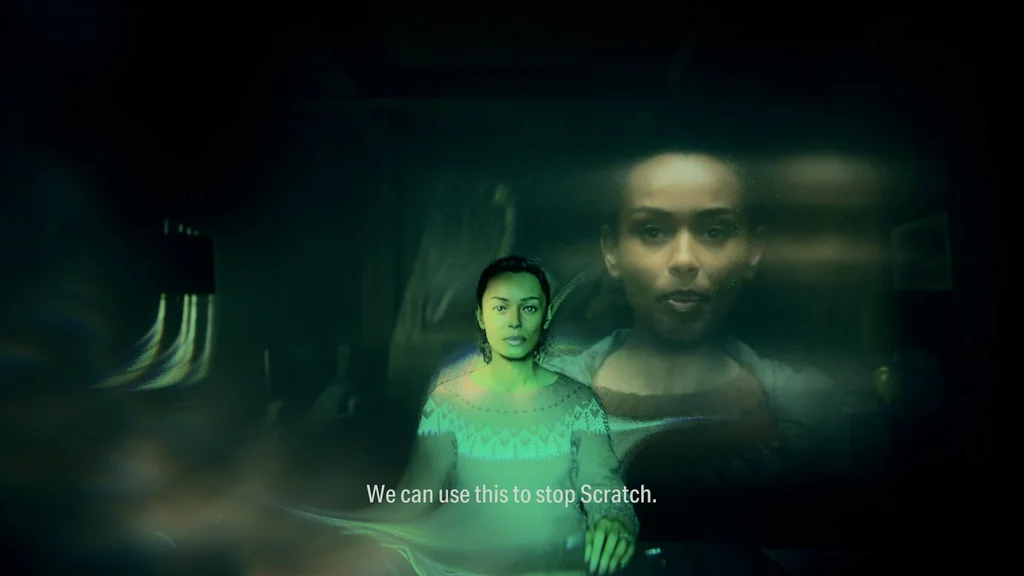

Saga Anderson gets trapped in the Dark Place when trying to save Alan so they can save her daughter, the town, and the world. The devs do an expert job communicating Saga’s anxiety. The Mind Place we’ve gotten so comfortable throughout the game with is warped and twisted. Index cards on her investigation bulletin board that used to hold irrefutable facts now contain fears, lies, insecurities, doubts.

I verbally whispered out loud, “Oh no.”

I really felt for Saga. I was empathetic to her indignation and rage that Alan had, without her consent or knowledge, written her into a story and effectively killed her daughter. Despite this, even as the very fabric of reality is changing around her and she’s dealing with things far above her paygrade (as agents from the Federal Bureau of Control are quick to point out), she rises to the occasion. She’s worked so hard to push past racism, sexism, family issues, and to keep her self-talk positive. To then be trapped in a cruel version of her own mind where all those doubts become reality… it’s probably my nightmare.

Yet, Saga works through it. She talks through each lie, every falsehood, processing her emotions and thoughts. Saga gets out of the Dark Place in approximately 15 minutes. It took Alan 13 years.

Sure, one could argue that since Saga has the power of being a Seer (whatever that fully entails) through which she can glean the truth from other people’s words, she does have some advantage. On the other hand, Alan can literally change reality with the power of writing, so you think he could’ve figured out something a bit sooner. Not only does Saga get herself out of the Dark Place, she comes up with a solution to their problems while she’s at it.

Alan isn’t just trapped in the Dark Place—he is the Dark Place. And there’s a part of him that prefers it that way.

A Tale of Two Cities

Throughout Alan Wake 2, players switch between two storylines. I did my best to balance out my playtime so I wasn’t stacking up a debt with either character. It was hard, though, because Saga’s section was just so good.

At first, I wondered if my frustration with Alan Wake’s half of the story wasn’t fair to him. I was much more interested in Saga Anderson’s investigation. Her story is fascinating, and the world design is beautiful. Saga’s levels were varied visually, featured a variety of interesting characters to talk to, and offered challenging combat. It was fascinating to see the shadows creep into the light of day, to parse out the double realities between found pages and the Taken’s obsessive comments.

In comparison, I grew tired of Alan’s levels. I often had to backtrack because of the plot board mechanic which lost its charm as the game went on. While I thought the creepy hotel and version of New York were beautifully rendered, I started to sprint through levels rather than bothering with the annoying shadow enemies. I made a point to find Sheriff Tim Breaker in each available level, but sighed when we couldn’t significantly collaborate or share any findings together. I frowned at the disturbing, gratuitous mass violence.

But as I continued to play, I became aware that it wasn’t just the level design that was turning me off of half the story. It was Alan himself. Which brings me to frustration peak number two.

Really? For This Guy?

In a post-credits scene, the player learns that Alice Wake is not in fact dead, but rather, she faked her suicide because she knew that footage would compel Alan to grapple with how he has been complicit with his demons and begin a cycle of growth. It’s a bit manipulative, but it worked, so I think, well, okay.

But then Alice explains that she’s going (or has gone) back into the Dark Place of her own volition, to essentially puppeteer master him on his journey of escape.

I rolled my eyes and groaned out loud. Really? For this guy? Alice, who has been undergoing severe psychological torture for years due to Alan’s alterego, is going to go into the Devil’s playplace for her shitty, self-important artist husband? C’mon, Remedy.

Both Saga and Alice are ambitious, thoughtful, generous women who work hard to be their own people while also being good wives. In Alice’s case, she is choosing to put herself through literal hell, during the height of her artistic career, to invest in the emotional growth of her husband. That epilogue did not give me hope or excitement about a DLC, but rather, I felt beleaguered.

It’s not just in Alan Wake 2, either. I recently played Spider-Man 2, and there’s a lot of realistically portrayed pain between Peter Parker and MJ. The new God of War games are hellish for Freya. Even Zelda has to suffer for Link to have a super cool sword in Tears of the Kingdom. These seem to be themes we cannot escape in video games, so what hope do IRL womxn have?

Video games are fantastical adventures, yet our culture seems stuck in producing stories of problematic cis-het relationships where a femme can’t ever get a moment to shine, rest, or be free of being responsible for her male partner’s baggage. If in video games I can travel through time and space, swing through cities on spiderwebs, and do god-like magic, it sure as heck would be nice if I could see a woman whose life doesn’t suck.

Alan Wake is impressive I suppose in that he reminds me of real life people I’ve known. People who say they want to get better, and then don’t. Who say they care about evolving, but don’t do the work. Who say they want something they’ve never had, but aren’t willing to do what they’ve never done before to get it… I argue that Alan consistently embraces the worst parts of himself.

Main Character Mood

I want to make it clear that I commend Remedy for their successful portrayal of Alan as an insecure, self-loathing artist. But I’m tired of the long-suffering male protagonists in video games and the women who have to put up with their nonsense. Alan Wake is not a good guy, and I feel there is a flawed glorification with him as the titular character. For me, the game is saved by Saga Anderson being a true deuteragonist, and even as Alan admits, the true hero of the game.

I understand the marketing desire to pitch this game as a sequel to a cult favorite by being called Alan Wake 2, but when Remedy decided to go all in on making Saga an equal character, I think there should have been a reckoning in the naming. To call this game Alan Wake 2 is not only a disservice to Saga Anderson who has an equal (if not more) amount of playtime, but a doubling down to the idea that Alan Wake is a character worthy of a title. Even the game’s cover art shows Alan looking haunted, a larger-than-life ghost, but the eye is drawn to Saga Anderson at the center, confidently walking into danger.

To paraphrase I Think You Should Leave, Alan Wake is a bad dude, Alice. Dump him, girl. Throughout the games, Alan is shown and/or described as having anger and substance problems. He’s not a good husband, that’s for sure, and he’s not a good colleague (to his agent in the first game, nor to Saga as a world-saving duo; like, cool that you made her a hero but it’s pretty rude to blithely kill their kid…). His self-importance is infuriating, and his obsession with his own creative output is more than a bit disturbing. Of course the Devil is able to reside comfortably in Alan.

For a man for whom writing is supposedly everything, Alan’s selfishness supersedes his knowledge of the craft. In the first game, Alan had to “balance the scales” in the Dark Place. He references literary and genre theory throughout both games. If Alan were to have experienced any plot ever, then he would know he probably has to die in order to save the world and keep Scratch/the Devil at bay. And yet, despite this, he insists on living and trying to escape, and women keep insisting on trying to save him. He is unaware that the Devil has come to reside in him full-time, so completely sure he is of his own value and self-knowledge. It takes far too long for Alan to give Saga a golden bullet and encourage her to shoot him.

I Want To Get Better

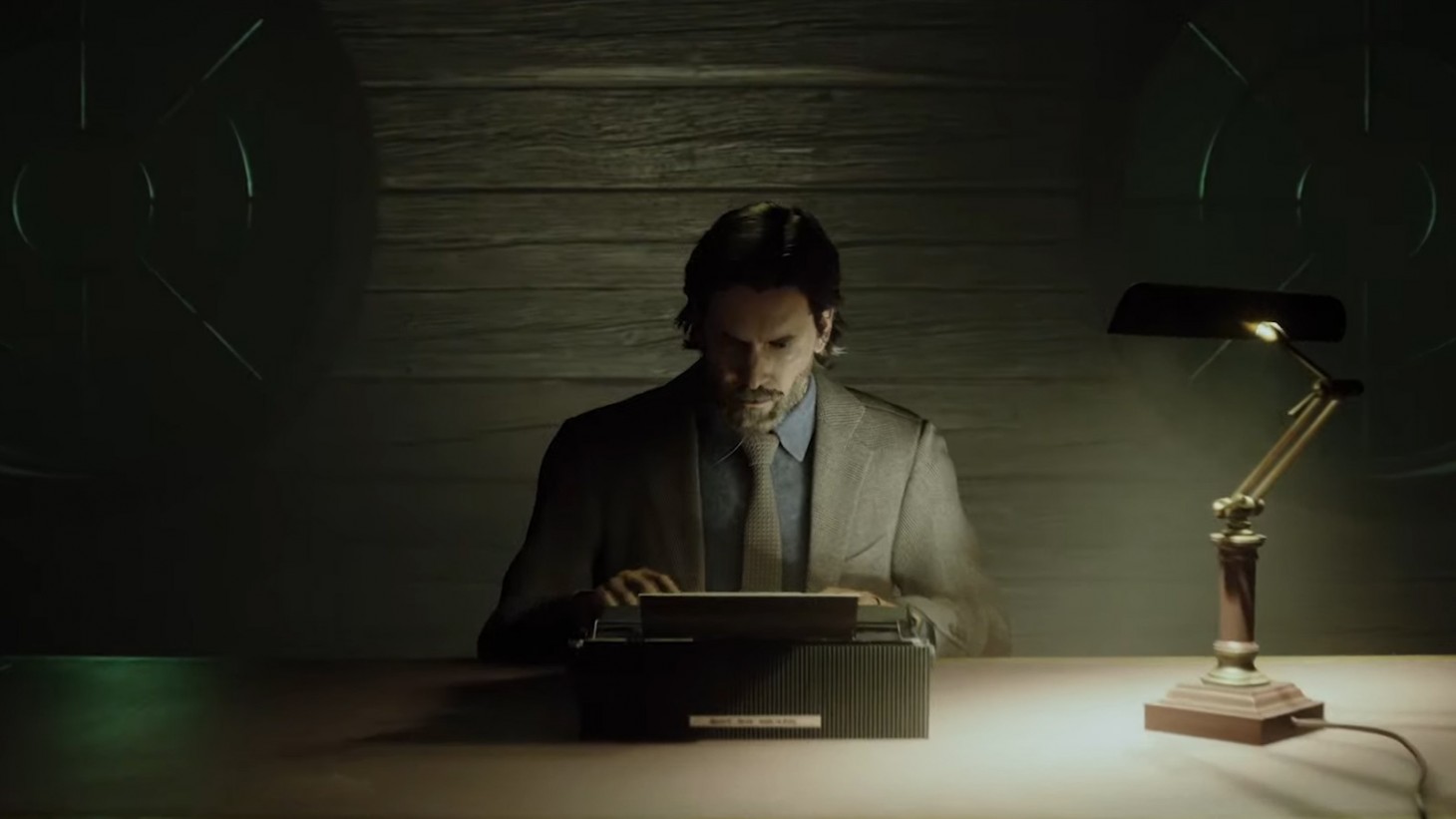

In the first game’s final moments, Alan sits at his typewriter in the Dark Place and enigmatically states, “It’s not a lake; it’s an ocean.” (Many people have discussed the meaning of this line.) At the end of Alan Wake 2, in a clear echo, Alan’s back at the typewriter (after getting shot by Saga and seemingly waking up again) though this time he says, “It’s not a circle; it’s a spiral.”

Aside from how annoyingly obtuse these sentences are (and again, I’m not sure he’s a good writer), it’s a clear indication that progress has been made. The spiral, rather than a circle, has a distinct beginning and end, and that, along with the Expansion Content Road Map for Alan Wake 2, means that there is more to our heroes’ journey from here.

What will be in store for Alan Wake 2 DLC or Alan Wake 3? Personally, I’d like to see a chapter that’s called Saga & Alice where they defeat the Devil all on their own. I’d be fine if I didn’t have to play as the long-suffering Alan Wake any longer or try to parse out what exactly his relation is to the mysterious, other jerk-artist, Thomas Zane.

But I do want to see Alan grow. I want him to succeed. I’d like to see him still believe in the power of his art while practicing some humility, to learn how to apologize without being self-flagellating, and to take some responsibility for his own spiritual growth. Anyway, this whole essay is to say…

Go to therapy, Alan Wake.

Amanda Tien (she/her or they) loves video games where she can pet dogs, solve mysteries, punch bad guys, play as a cool lady, and/or have a good cry. She started writing with The Punished Backlog in 2020 and became an Editor in 2022. Amanda also does a lot of the site's graphic designs and podcast editing. Amanda's work has been published in Unwinnable Monthly, Poets.org, Salt Hill Journal, Aster(ix) Journal, and more. She holds an MFA in Fiction from the University of Pittsburgh. Learn more about her writing, visual art, graphic design, and marketing work at www.amandatien.com.