Silent Lucidity

Some of the best video game experiences of the last decade or so have existed in the form of the wordless story. Such games give the player little to no direction, no context, and no chatter; they subsist on environmental design, simple gameplay, and vibes. It’s difficult to pull off this level of narrative scarcity without making the game seem pointless, but the latest effort from ex-Playdead staff Jeppe Carlson and Jakob Schmid manages to strike that balance, despite a few bumps near the end.

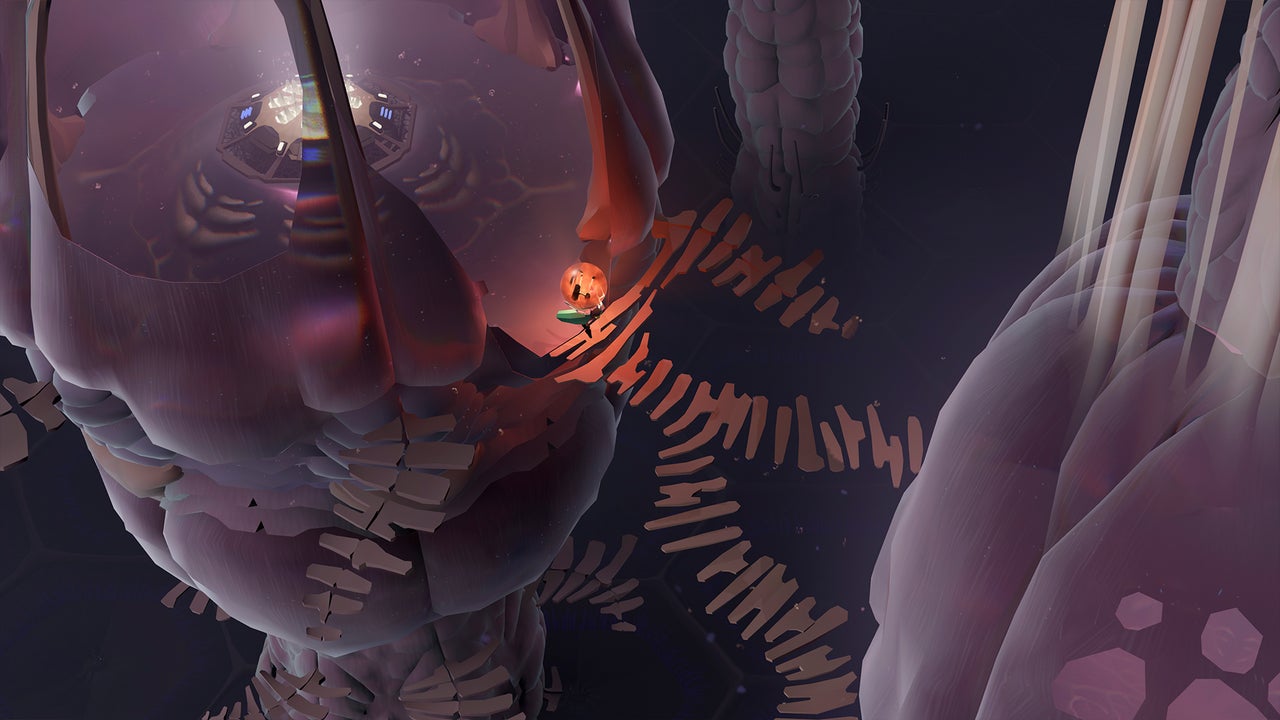

Geometric Interactive’s rookie effort Cocoon is the latest in a long line of wordless games, offering the player the opportunity to exist as a nameless, flightless bug who must solve environmental puzzles and fend off the occasional behemoth to move forward. Much like Playdead’s masterpiece Inside, at no point does Cocoon make clear to the player where they are, why the world exists the way it does, or even what their goal could possibly be.

To tell the truth, I’m still not entirely sure what this game is about in a broader sense. Perhaps an allegory for the Big Bang? What an average life cycle feels like, in a metaphysical way? What it’s like to be born and see the world for the first time, where everything appears fantastical and perplexing? Maybe that one’s life doesn’t really begin until reaching full growth and maturity?

Whatever you make of Cocoon’s greater meaning, it’s an enthralling experience, one that captivates the player with its unique environmental design, brain-busting puzzles, and enchanting (yet somewhat unsettling) ambiance. I may not have truly figured out the purpose of any of my actions in Cocoon, but it consistently drew me in and impressed me enough to keep going.

Breaking Free

The game starts with the player emerging from—you guessed it—a large cocoon and making their way through a number of environmental puzzles until they discover an orange orb. This orb is, essentially, a portable world, one that not only helps the player open pathways and unlock moving platforms but also creates a doorway between distinct realms when placed on certain pedestals.

I may not have truly figured out the purpose of any of my actions in Cocoon, but it consistently drew me in and impressed me enough to keep going.

As the experience unfolds, this unnamed bug finds more balls with different distinct capabilities. For example, the orange ball generates new pathways, while the green one lets the player activate ascending or descending platforms. Additionally, players must carry these orbs in and out of different worlds to solve specific puzzles, such as bringing the orange orb into the green world to activate previously inaccessible pathways.

Each time you uncover a new orb in Cocoon, you’ll face off with a large boss in classic David-vs-Goliath fashion. In these moments, you must problem-solve your way to identifying and hitting a certain weak point. These moments are the only combat sequences in the entire game and excel at breaking up the slower, more cerebral approach to puzzle-solving gameplay with something more intense and engaging.

A Bug in the System

Cocoon’s biggest gameplay drawback, however, occurs in the latter third of the game, where some of the most complex brainteasers require the player to move between orb-worlds very frequently and even create some small Rube Goldberg-like systems to progress. While these challenges appear fairly impressive on paper, the number of actions needed to complete them makes the whole endeavor a little tedious, which harms the pacing of the game’s final acts. I’m all in favor of raising the difficulty in the latter parts of any game, but some of these puzzles just felt tedious.

Despite these aforementioned slower sequences, every bit of the gameplay is a treat, with simple and intuitive mechanics and seamless movement. For a game that only utilizes a single button, Cocoon offers a welcome variety of potential actions ranging from simple pick-up-and-place prompts to timing-based attacks, so there’s rarely a dull moment. Carlson and company have taken the Inside and Limbo philosophy of minimal yet diverse inputs and translated it beautifully to isometric, puzzle-laden lands.

Worlds Within Worlds

While Cocoon’s problem-solving gameplay serves as the crux of the experience, its greatest feature might be its world architecture. Despite having completely linear progression, Cocoon’s overworld and orb-worlds rely on labyrinthine design, with new areas appearing to have multiple routes toward progression but only allowing the player to take one or two routes at any given time. As a result, the game feels like a Metroidvania at certain points, but without the same level of backtracking; you return to previous areas usually through finding new pathways to them or portal-jumping.

Much like Inside, the environments of Cocoon amazed me and flummoxed me all at once.

The frequent travel between portals (as well as phasing in and out of orbs) can be a bit jarring. The seamlessness of such actions, however, makes such travel fairly enjoyable, and the trippy nature of these movements enhances Cocoon’s mysterious atmosphere, as I frequently found myself in awe of its near-flawless interconnectivity.

Shine a Light

Even in its most frustrating moments, Cocoon is absolutely gorgeous. The more structurally disturbing areas have some of the brightest, most beautiful colors, and some of the most kinetically beautiful sequences occur in particularly hostile locales. The faint glow of each orb brings an optimistic shine to even the most threatening of places, making the journey a visual delight.

Cocoon’s worlds teem with mystique and intrigue. Each area mixes classic video game biomes (e.g., desert or swampland) with its own misshapen statues, bizarre machines, fleshy nodes, and celestial beings. The player must travel through lands simultaneously defined by futuristic technology and inhuman fantasy, and as a result can’t possibly predict what they will see next.

The meshing of different environmental themes adds to the constant sense of confusion and unease. I never knew why these worlds were the way they were, but I still forged ahead solving puzzles with aplomb, hoping at some point to unlock some visual explanation of what was happening. Much like Inside, the environments of Cocoon amazed me and flummoxed me all at once.

The End Is the Beginning

Even after rolling credits, I find myself in continued cogitation about my experience with Cocoon. The final moments illuminate so much and so little at the same time; it’s as though I finally understand how the game is supposed to make me feel rather than whatever events had just transpired over my roughly four-hour playthrough. Cocoon’s ending is energizing and awe-inspiring, yet I’m still not sure I can fully explain it to someone if asked to do so.

While I wouldn’t say Cocoon achieves wordless narrative perfection, it succeeds in presenting a story full of emotional resonance and mental stimulation with little to no communication to the player. What results is a great video game, and more importantly a great work of art, one that causes those who engage with it to mull over its events, its structure, and its atmosphere.

Score: 8.7/10

LIGHTNING ROUND THOUGHTS:

- The music of Cocoon is subtle and unintrusive, though as such it’s not especially memorable.

- One exception to the previous statement: There’s a synth-heavy jingle that plays whenever you solve a particularly difficult puzzle, and it’s great.

- There is some side content in the form of releasing all of the Moon Ancestors, but it’s not necessary, and I’m not sure there’s any reason to do it outside of achievement/trophy hunting.

- To be honest, I did have to use a guide for a handful of late-game puzzles that were more frustrating than mentally stimulating. I don’t regret that one bit.

Cocoon released on September 29, 2023, for PC, Nintendo Switch, Xbox One, Xbox Series X/S, PlayStation 4, and PlayStation 5. It is also available on Game Pass.

Sam has been playing video games since his earliest years and has been writing about them since 2016. He’s a big fan of Nintendo games and complaining about The Last of Us Part II. You either agree wholeheartedly with his opinions or despise them. There is no in between.

A lifelong New Yorker, Sam views gaming as far more than a silly little pastime, and hopes though critical analysis and in-depth reviews to better understand the medium's artistic merit.

Twitter: @sam_martinelli.