I’m lost again.

Is that the same house I just passed?

The same room?

The same door?

The same giant smiling face?

I can occasionally be directionally challenged. Truth be told, if you can name a type of place, I’ve found myself lost there (or, more embarrassingly, my spouse has). I often don’t mind, as I get to see some really cool corners of the world by getting lost in its more unassuming spaces.

I often find a little comfort in navigating video game spaces, even if that comfort is coated in yellow paint or conveniently placed lighting.

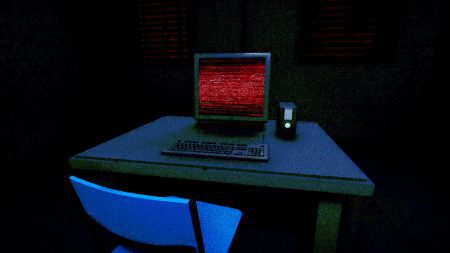

Montraluz’s Dreamcore initially invokes this feeling of just losing yourself. As a disembodied, first-person walker, the player is dropped into a world where getting lost feels like the point. It plays a bit like a Twilight Zone episode starring the street-walking flâneur.

The developers describe Dreamcore as “a psychological horror game based on liminal spaces.” The true horror here may be how much this reveals about one’s own reactions to being trapped in endless, picturesque loops without a soul to talk to or many interactable objects. Unlike my experiences in real life, the charm wore off quickly.

Lost in Space

For both of the current levels of Dreamcore, the opening load screen tells players to pay attention to their surroundings and that “being lost is the least of your problems.” This gives a false sense of dread that I found unwarranted during my seven hours with the game.

Dreamcore currently consists of two levels: Dreampools and Eternal Suburbia. Montraulz boasts that Dreampools consists of 500 rooms and that Eternal Suburbia consists of 150 houses.

I absolutely believe them.

These are incredibly crafted liminal spaces with a timeless quality about them. They each feel like their own unique modern hellscape to get lost in. Dreampools boasts white tile walls, blue pools of water, and colorful waterslides that as far as I can figure you cannot slide down. Eternal Suburbia feels like navigating a nuclear facility that never received its bomb—a suburban hellscape where the interior designs of homes are far more interesting than their white picket fences.

Getting lost in Dreamcore’s levels feels like the point. Both levels present fairly open-concept puzzles to solve with the goal being to escape. There are environmental hints from sounds to visuals that help along the way; meanwhile, Dreamcore tells the player very little. There were moments when I wasn’t sure if I was hearing new music or if my mind was feeling the space with what it hoped or sought to find.

Paying attention to your surroundings is essential, but being lost might be the most severe of Dreamcore’s problems.

Liminal

Liminality, like uncanny, is one of the best (and frankly worst) English major words. (Trust me: I have three English degrees. I have overused the word liminal to the point of absurdity.) Here, the developers are actively contributing to a larger project on liminality, with even the project’s name seemingly reflecting this influence. Dreamcore builds on the rise of “dreamcore” as liminal horror spaces on the internet. They focus on the horror just beyond the familiarity of modern art, architecture, and design.

This works great as a series of urban still lives. Concrete structures, tiles, or suburban houses sit without explicit human (or even animal) interaction. Still lives possess a sense of rotting; dreamcore art, at times, seems to do the opposite and, in turn, creates a sense of plastic permanence. Those perfect white tiles in the pool area may forever stay perfectly white. This lack of decay creates a sense of unease. As individual scenes or shots, they linger with the viewer.

Dreamcore leans heavily on this permanence. These are spaces that must have been built by someone, right? The player navigates a series of spaces that could double as an interactive art installation. The lens noises that occur when the player zooms in or out help create this illusion. At its best, I felt like a tourist in the worlds of Dreamcore, consumed by the unrotting, unaffected art around me.

I struggled with these spaces as a puzzle game and even more so as a horror game. To call this game horror feels like misidentifying—or, worse, maybe misunderstanding—the genre. My sense of unease quickly gave way to frustration. The game’s puzzles aren’t unsolvable, but nothing really drove me to solve them other than to do something or hope for any interaction.

Dreamcore (the art) might work best as still shots or brief moments. The seemingly endless loops of Dreamcore (the game) rob it of its charm and beauty. Its haunting endlessness plays out like a Twilight Zone episode without a plot.

Closing Thoughts

Dreamcore captures the imagination and serves as a nice proof of concept for what liminal space horror could look like in modern game engines. Sadly, it currently doesn’t feel much more than a pitch, and worst yet, one that outlasts its welcome.

Eternal Suburbia is the stronger of the two current maps available in Dreamcore, and the developers promise that three more will be released in the coming years. The game is thus only two-fifths complete.

I look forward to visiting the spaces the team creates, and I’m excited to get lost in the new little corners of these dreamlike worlds. I’d just like them to scare me beyond the idea of getting stuck in an endless loop.

Score: 5.5/10

Dreamcore, developed by Montraluz and published by Tlön Industries, is available now on PC, PlayStation 5, and Xbox Series X/S. MSRP: $8.99. Version reviewed: PC.

Clint is a writer and educator based out of Columbus, OH. You can often find him writing about Middle English poetry, medieval games, or video games. He just finished a PhD in English at the Ohio State University. You can find his academic and public work at clintmorrisonjr.com.

2 Comments

I’m scared of that smiley face ball:(

love it, best game around by far and I wish they could add something, makes it extra fun and never get bored. I love the game so much! Add something like, monster or monsters follow you, Jump scares, Ghost or Spirit appear doing something or make a sound, lights flickering on and off, etc. All this would be random location with the option of turn On or Off. Thanks!