Welcome to Punished Notes, Volume 17! For this edition, I will examine the HD remaster of one of the weirdest games Nintendo has ever made. These notes will include some story spoilers, but be honest: This game came out 10 years ago. You’ve had the time. Also: I’m not going to explain every little part of the game’s story or progression (or the history of the franchise), so Google all of that if you want to know more.

A Complicated Classic

The Legend of Zelda: Skyward Sword has the most complicated legacy of any game in the decades-old franchise. It’s easily the most polarizing entry in the series: Most people love it or hate it, with detractors calling it the lowest point of the franchise and supporters viewing it as a necessary step forward. Centering the entire experience around motion controls and a detailed narrative, Skyward Sword may well have been Nintendo’s most ambitious Zelda game when it first released on Wii in 2011—though many of its attempts to expand its audience turned away longtime fans, many of whom loathed the title’s linearity, easiness, repetition, and endless tutorials.

Having replayed the HD remaster for Nintendo Switch, I’ve largely come to the same conclusion I did the first time around: Skyward Sword is the worst great game ever made. It’s a near-masterpiece with the most glaring and undeniable flaws. Not even the Nintendo apologist in me can defend some of this game’s greatest failings. And still, I love it.

When the title first released, players grumbled about the backtracking, tacked-on motion mechanics, and constant hand-holding from Fi (a spirit who guides the player through the experience), and I could never really argue against any of those complaints. Fi was incredibly annoying, with frequent unskippable dialogue sequences that often told the player how to solve the game’s puzzles. While I enjoyed the motion controls for combat and item use, having to guide Link with the Wiimote for swimming and rope-swinging felt awkward and pointless.

Additionally, Skyward Sword is easily the most linear game in the franchise. This isn’t in and of itself a bad thing, but linear titles typically don’t task the player with going in and out of separate zones constantly. The backtracking can be especially tedious in the story’s later hours, when the player has largely grown weary of traveling to the same places over and over again, even for brand new tasks. And while the dungeons are phenomenal puzzle boxes full of genuine challenge and intrigue, many are peppered with stone tablets outright explaining what you’re supposed to do, and that’s outside of Fi pointing everything out like an overzealous tour guide.

Honestly, these design decisions are irksome to say the least (and downright grating at times), but they’re mostly overshadowed by the game’s strengths. Beyond the jankiness and hand-holding is a wondrous experience with some of the franchise’s best dungeons and story beats. The watercolor art direction is delightful, the powerful soundtrack (Skyward Sword is the first game in the series to have a full orchestral score) breathes life into every single moment, each individual region is full of fun and rewarding tasks, and the floating hubworld of Skyloft contains some truly lovable characters and locales. No amount of over-tutorializing could get in the way of so much heart and so much beauty. And while many despise the overuse of motion controls, the tactility of swinging your sword at just the right time (in exactly the right direction) results in satisfying and engaging combat. Everything that works about Skyward Sword achieves a kind of feeling I only get with other top-tier titles, despite its faults. Yet the faults remain.

Going Through the Motions

Much of the discussion on the legacy of Skyward Sword has centered on its controls, which in the original Wii version were almost entirely motion-based. Used as a way to promote the Wii MotionPlus accessory, the game was designed to showcase the most immersive experience the Wii could offer in an AAA title. Players would use the Wii controller to swing their sword in a particular direction, aim their bow, pilot Link’s Loftwing (a large bird-like mount), and even throw or roll objects. In addition, Skyward Sword forced the player to use motion controls for actions such as swimming, riding a railcar, piloting a beetle drone, and swinging from ropes.

While many of these mechanics work fine, a lot of players hated them, and it turned a lot of people away from the game. Sure, the idea of having to swing your sword in a direction the enemy couldn’t block added some authenticity to the experience (and turned every encounter into a mini-puzzle), but it always felt awkward to have to use a pointer for basic actions like flying on a mount or throwing a bomb.

Luckily, Skyward Sword HD introduces a new button-only mode that does away with all the Wii-centric controls and maps sword swings to the right stick, tasking the player with flicking the stick in the direction they want to thrust their blade. While the new control scheme also forces the player to hold the left bumper in order to move the camera with the right stick (since simply moving the stick in any direction draws your blade), I never had too much trouble in my playthrough switching between camera mode and sword mode, even if the very idea of relying on a button for camera controls felt counterintuitive.

I originally didn’t like the idea of button-only controls for Skyward Sword, and not because I thought the Wii controls were perfect by any means. While I certainly had mixed feelings about many parts of the original game, the motion controls were a quintessential part of the gameplay; almost every single aspect of each dungeon, puzzle, and location was built around them.

It didn’t take long for me to accept that the button-only mode was not only superior to the motion mechanics, but also vastly improved the overall experience. Flying the Loftwing wasn’t nearly as cumbersome or exhausting. Solving puzzles around throwing bombs into a bowl didn’t frustrate me at all. And while the sword combat lost some of its magic, it was nearly as stimulating and exciting with the right stick (and generally more accurate, making certain battles a lot less annoying).

Since I didn’t have to recalibrate the controller or worry if I was “up for it” every time I turned on Skyward Sword, I was able to truly admire its most special elements. In particular, the game has perhaps the best set of dungeons of any Zelda title. From the time-bending mechanics of the Lanayru Mining Facility and Sandship to the architectural twists and turns of the Sky Keep, each dungeon presents a scintillating blend of aesthetic excellence, structural challenge, and near-perfect pacing. I had always loved Skyward Sword‘s dungeons, and they remain as incredible as ever. Also, with maybe one or two exceptions, each dungeon’s boss fight ranges from decent at worst to incredible at best (Koloktos in the Ancient Cistern might be the best non-Ganon boss battle in the whole series).

In addition, the lack of motion controls made engaging in Skyloft’s wonderful set of side quests far more appealing. Since many of the quests themselves involved something motion-related in the original, I never really cared enough to do many of them the first time around. In my HD playthrough, I did every single one of them with aplomb.

Typically, I don’t think remakes or remasters should outright banish the original work into obsolescence. There’s tremendous value in playing games the way they were meant to be played, even if a lot of aspects don’t hold up over time. Mechanically speaking, however, Skyward Sword HD may be the exception, since I can’t ever see myself picking up a Wiimote and Nunchuk again to play this one. I’ve grown too accustomed to the convenience of the Switch controls, and I don’t think I can go back.

All in All is All Wii Are

The improved controls and quality-of-life updates (which allow players to fast-forward through dialogue, skip cutscenes, and ignore Fi’s constant yammering) make Skyward Sword HD a much more streamlined experience. Beyond obviously making the game more accessible and playable, such upgrades allow the player to focus on what really makes the game sing: its captivating story, enchanting dungeons, and colorful cast of characters.

Skyward Sword is canonically the first tale in the Zelda timeline, depicting the origins of the Triforce, the Master Sword, and the land of Hyrule itself. Dragon gods Eldin, Lanayru, and Faron serve as the early embodiments of the magical spirits Din, Nayru, and Farore, all staples in the Zelda universe. Species like the Kikwi and Parella inhabit the surface (both clear nods to the Deku and Zoras), and Gorons roam the land just as they have in nearly every series entry since Ocarina of Time.

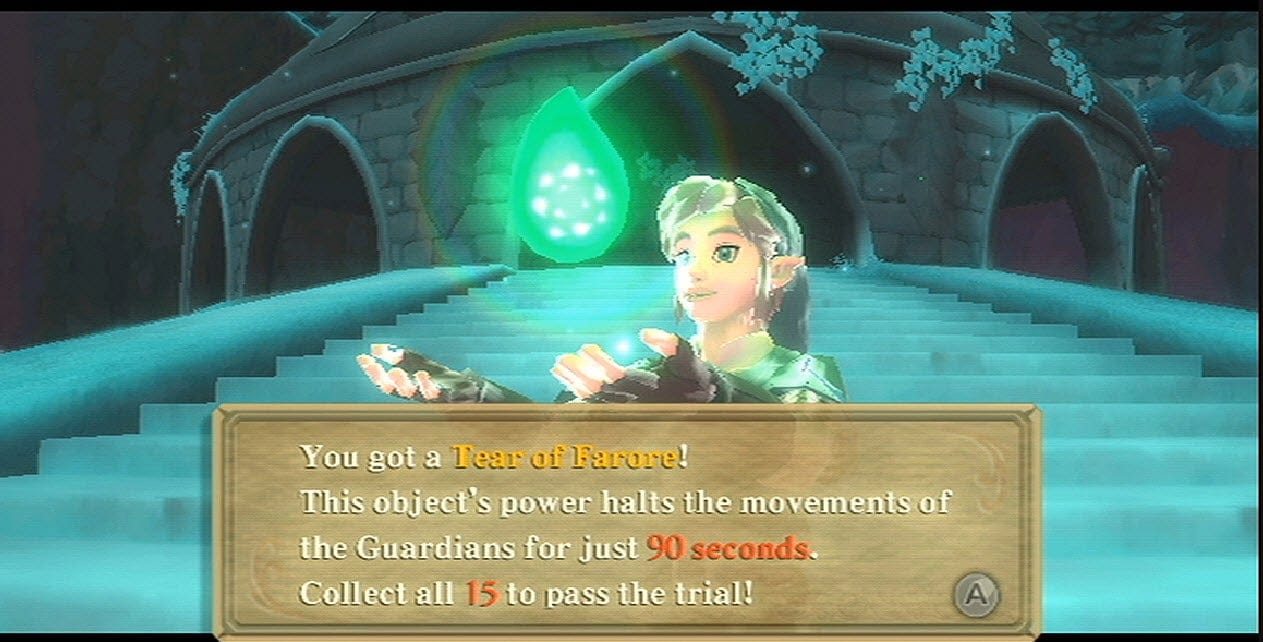

Beyond that, the protagonist’s journey serves as an origin story for all subsequent Hylian legends. Link has always been known as the hero of time, but in Skyward Sword, he starts the game with a reputation for being lazy, unskilled, and completely unprepared for the dire challenges ahead of him. Most of the game’s dungeons exist as “trials” for Link himself, not just to demonstrate his courage, but to prove whether he’s in any way capable of defending himself or anyone else.

While every Zelda game has its schlocky narrative reasons for Link to collect a variety of objects from numerous dungeons, Skyward Sword frames a large chunk of it as training, whereas in games like A Link to the Past or Wind Waker, it’s accepted early on that Link was born to be the one to save Hyrule, and the various macguffins he acquired on the way to fighting Ganon were part of either making him stronger or opening up a certain pathway. Every game starts with Link being compared to some original hero of time, and clearly the Link from Skyward Sword had to prove himself more than anyone else.

The motif of what it means to be heroic goes beyond Link’s quests through treacherous lands. Groose, a classmate of Link who bullies him and vies for Zelda’s affection, eventually follows Link to the surface in an attempt to usurp the role of savior, only to realize he’s in way over his head. Instead of sulking and giving up, Groose finds a different way to be useful, namely through constructing a defense system to protect the Sealed Grounds from the occasional emergence of the Imprisoned (a monstrous form of the main antagonist Demise). Changing from the embodiment of toxic masculinity into an enthusiastic and altruistic assistant has made Groose one of the more beloved side characters in the whole franchise, and part of his character development is grounded in the notion that you can be a hero without being the hero.

Much of the title’s side content underscores this theme. Early in the game, the player meets a friendly demon in Skyloft named Batreaux, whose only wish is that Link does favors for everyone around town. Doing so will earn Link gratitude crystals, which Batreaux believes will ultimately cure him of his hideous appearance and turn him into a normal human. While Link performs these side quests for a clear reward, the tasks themselves often revolve around either making people’s lives easier or allowing them to achieve some kind of wish or goal.

To be clear: Some of these quests are as mundane as cleaning someone’s house or fetching a random item from the surface. But for the most part, they highlight Skyward Sword‘s focus on earning heroic clout through targeted acts of kindness. There’s nothing essential to the main plot about the player finding Beedle’s favorite bug, fixing Dodoh’s Fun Fun Island attraction, or playing matchmaker for Pipit and Karane, but every single person is delighted that Link would help them with something so otherwise trivial. The player’s rewards for these quests go beyond some rupees or item upgrades; the greatest reward is the privilege of protecting the happiness of Skyloft, even in the darkest of times.

This form of micro-heroism extends to the surface areas as well, where finding dungeons (and sometimes navigating through them) involves communicating with and assisting nearby locals, who are just as terrified of the evil moblins as anyone else. You can’t get through the Fire Sanctuary without freeing Mogmas from bondage, and you won’t be able to find the Skyview Temple without protecting the Kikwis from nearby enemies. To an outsider like Link, who has never been to these places before, locales such as the Faron Woods, Eldin Volcano, and Lanayru Desert come off as mysterious and even daunting, but to so many others, they’re home. Characters like Bucha, Plat, Jellyf, and Skipper are grateful to Link, not because they pay much mind to his loftier endeavors, but because he provided help when they needed it.

Ultimately, the ways Link interacts with and saves people both close to and entirely unfamiliar to him exemplifies why I’ve always defended Skyward Sword as great despite its shortcomings. This is a game that really cares about people. It cares not just about their general safety and well-being, but about their homes, their culture, and their happiness. Link isn’t just there to save the princess and the realm at large; he’s there to be an all-around good samaritan, who cares just as much about making scared critters feel safe as he does about bringing down demonic forces of terror.

The Legacy of Skyward Sword

The Legend of Zelda: Skyward Sword originally released in late 2011 during a year when a lot of major shifts in gaming occurred. The word “linear” began to feel like a pejorative, as major AAA franchises shifted toward providing more open-ended experiences, as best exemplified by the popularity of The Elder Scrolls V: Skyrim, which came out the same month as Skyward Sword. In addition, many players had grown tired of the industry’s penchant for providing too much information in-game and making experiences too player-friendly, hence why so many fully embraced Dark Souls as a game that defied AAA conventions around difficulty and fail-states. And for games that still presented largely linear stories with optional easy modes, developers offered more “mature” stories with a greater emphasis on character development and voice acting (L.A. Noire), more cinematic gameplay sequences (Uncharted 3: Drake’s Deception), bombastic combat mechanics (Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 3), or brain-busting challenge (Portal 2).

Despite receiving largely positive reviews during its launch window, Skyward Sword could not have come at a worse time. It was too easy for so-called “hardcore gamers,” yet it was still too grand and ambitious for casual players to fully embrace. The main audience Nintendo had targeted with the Wii and DS had mostly shifted over to mobile gaming, and longtime players with high-end PCs and multiple consoles wanted the Big N to showcase something similar to what they’d been getting from everyone else: less restriction, more emotional gravity, and higher difficulty. By presenting large, complex dungeons with a byzantine control system just to spell out every possible challenge and puzzle combination, Skyward Sword was trying to have its cake and eat it too.

The reality of the Wii era was that a lot of people viewed it as too gimmicky to take seriously, and that Nintendo had essentially spurned its veteran audience in favor of creating experiences for your grandparents and small children. For the most part, though, Nintendo’s top-tier franchises were the exception. Mario Kart Wii cultivated a strong competitive scene. The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess, a launch title for the console, had the darkest tone and art direction in the franchise. The Super Mario Galaxy games had plenty of challenging levels and awe-inspiring cinematic qualities. And while Metroid Prime 3: Corruption was super heavy on motion controls, it was still an action-packed Metroid game that didn’t deviate too much from what longtime fans had grown to love.

When Skyward Sword came out, however, it was almost as though Nintendo had taken a step backward. It had abandoned the gravitas of Twilight Princess in favor of something more childlike, similar to the cel-shaded visuals of Wind Waker, though somehow not quite as charming. Instead of making the world more expansive and open-ended, Skyward Sword presented the most linear Zelda experience imaginable, with fragmented regions that effectively funnel the player toward every point of interest. And even after giving the player elaborate dungeons and puzzle-box worlds, Nintendo basically told you how to do every single little thing, eliminating many of the “aha” moments that have made the Zelda series so satisfying. The quality-of-life updates in SSHD mitigate some of these issues, but the game is still a breeze regardless, and those stone tablets explaining puzzles haven’t gone anywhere.

I completely understand why so many people flat-out despise Skyward Sword. It’s more than just a random game that didn’t click with them for any number of reasons. It was something crafted in the image of what they wanted, but was clearly made with a more casual audience in mind, despite being a 40-hour experience. In many ways, that’s the greatest sin any developer can commit, at least in the eyes of “gamers”: releasing something that, fundamentally, isn’t meant to serve them directly. You see this in the way many internet commenters react to things like Nintendo Labo, mobile games, and the Just Dance franchise. These are not meant for us, therefore video game company X is wasting its time.

Everyone is allowed to feel how they feel, and I’m never the one to yell, “Let people enjoy things!” as that’s often a way to suppress genuine criticism. But a unique vitriol surrounds Skyward Sword, and I really do believe it’s because many players felt Nintendo didn’t give them the respect they thought they deserved. It couldn’t just be a game they didn’t like. It couldn’t have been a failure that we all moved on from. No—it had to mark the end of Nintendo, the end of Zelda, and present an existential threat to “hardcore” gaming, or at least Nintendo’s role in it.

But here’s the thing: None of that is true. Breath of the Wild gave Zelda fans and core players exactly the experience they wanted, and it even carried over many mechanics and systems from Skyward Sword (e.g., stamina meter, sailcloth, crafting, breakable weapons). Nintendo had a few challenging years after the game’s release, but bounced back in full effect after the launch of the Switch. In between all this, The Legend of Zelda: A Link Between Worlds launched for the 3DS. While the game was also an extremely easy endeavor, it was more well-liked due to its open-ended nature and, well, its lack of motion controls. All in all, Skyward Sword was basically just a game that came out, and some people liked it and some people didn’t.

If you hate Skyward Sword, that’s fine. If you like some parts but dislike many others, that’s fine. It doesn’t have to be anything more than that. Either way, it’s just a game. For some, it was a failure. And it’s OK to just leave it at that. Meanwhile, I’ll still be here enjoying it, warts and all.

LIGHTNING ROUND!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

-While the repeated boss fights against the Imprisoned and Ghirahim (except maybe the third time) are still annoying, they were all much easier to play in button-only mode, and therefore didn’t bother me as much this time around. It’s still dumb that you fight the Imprisoned three different times, though.

-I know I’m not the first person to point this out, but the actual depiction of Zelda herself in Skyward Sword is great, and the chemistry she has with Link in the title’s early hours is palpable and touching.

–Skyward Sword is full of ideas that are good enough on their own, but are largely unnecessary. Examples: Silent Realm challenges, Tadtones, Scrapper deliveries. Getting rid of these would be addition by subtraction, even if they’re fine on their own.

-My favorite thing about Skyward Sword‘s dungeons is that they all force the player to utilize nearly every item in their inventory at some point or another. This is why Skyview Temple is easily the worst dungeon in the game, since the player enters with only the slingshot, while the Sky Keep might be one of the most clever dungeons in the whole series.

-The restricting of Fi’s explanations in this remaster has made the game far more enjoyable, to the point where I’m genuinely flummoxed Nintendo featured her so prominently in the first place.

-Another random mechanic that’s far better in button-only mode: playing the Goddess Harp. I love how Zelda games utilize instruments to make the world feel more culturally real, but it’s so hard to get the cadence of playing a string instrument correctly with motion controls.

-I like how the game uses the whole buffalo; repeating areas might be annoying but there’s very little negative space. Every part of the world serves a particular purpose, with very little emptiness (outside of, well, the empty sky around Skyloft).

-Scaldera and Tentalus are the two of the worst-looking bosses I can imagine in a Zelda game. The battles against them are fine, but they just look ridiculous.

-Random things I loved: goddess cubes, Batreaux, timeshift stones, item upgrades, boss rush mode

-Random things I hated: not enough sky islands, being attacked by cat-things at night, yellow chuchus, lack of fast travel (unless you buy an expensive Amiibo), not enough sky battles

Sam has been playing video games since his earliest years and has been writing about them since 2016. He’s a big fan of Nintendo games and complaining about The Last of Us Part II. You either agree wholeheartedly with his opinions or despise them. There is no in between.

A lifelong New Yorker, Sam views gaming as far more than a silly little pastime, and hopes though critical analysis and in-depth reviews to better understand the medium's artistic merit.

Twitter: @sam_martinelli.