I first played 80 Days, an interactive version of the iconic Jules Verne novel that has players attempt to circumnavigate the globe in as many days, on an airplane. I thought it would be a nice way to pass an hour. Not only did it last me the entire flight, but I continued to obsessively play it even when I reached my destination.

In 80 Days, Players take on Passepartout, assistant to Phileas Fogg, and manage travel plans and careful packing. I was entranced by a myriad of incredibly diverse NPCs as I discovered secret societies, made dangerous alliances, and connected long-lost loves, all while on the go. In 2014, 80 Days was so unlike anything I had ever played before. My enthusiasm led me to do something I hadn’t before, which was to look up the name of the studio and memorize it—inkle.

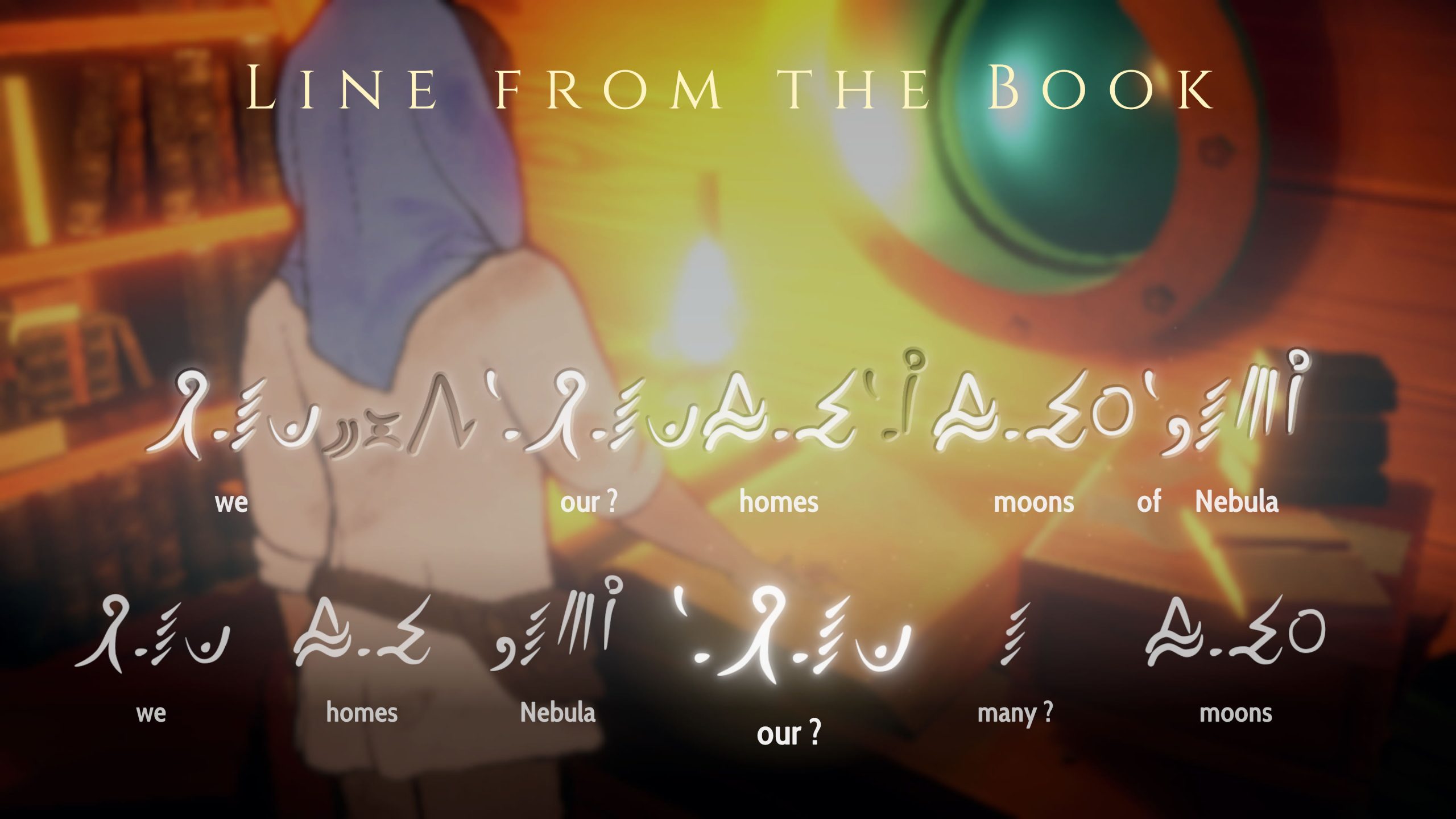

Time magazine named 80 Days its Game of the Year in 2014, and the following year, it received 4 BAFTA nominations. Since then, inkle Studios, based in Cambridge, UK, has continued to make innovative games that experiment with genre. From 2013 to 2016, inkle released a four-part epic adaptation of Steve Jackson’s Sorcery! that emulated classic paper-and-pen medieval adventuring; 2019’s Heaven’s Vault explored linguistics and translation, garnering attention from The New Yorker and winning Excellence in Narrative from the Independent Games Festival; 2020 brought a beautifully told rendering of the Knights of the Round Table with Pendragon; and 2022’s Overboard! was a gorgeous whodunit where players are the criminal, lauded by an Apple Design Award.

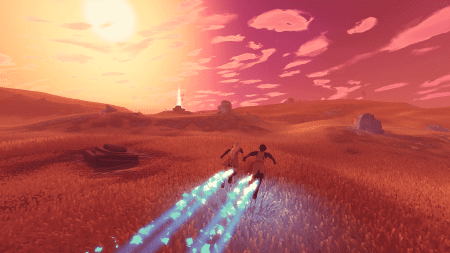

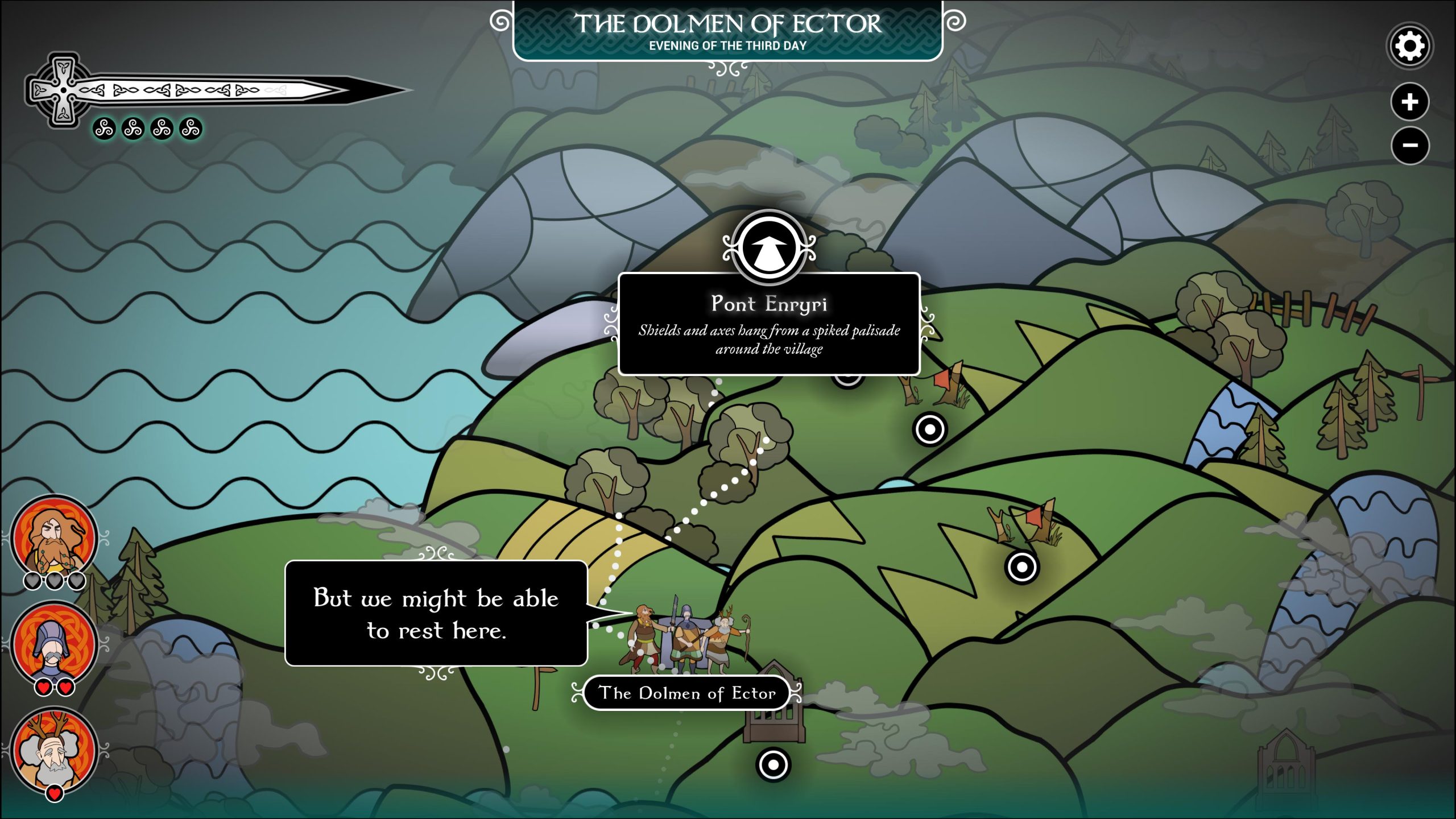

Last month, inkle launched A Highland Song. It has the most ambitious technical gameplay of any of inkle’s titles, utilizing the studio’s proprietary engine (ink) along with Unity. It diverges from the studio’s usual reading experience, and invites players to walk, run, climb, and leap through the Scottish highlands. A Highland Song is such a beautiful journey that it was featured at the Tribeca Film Festival, which highlights stories in gaming.

As a longtime fan (clearly), I was excited by the chance to talk to Jon Ingold, Co-Founder and Narrative Director of inkle, about how to design games with curiosity, the process of building big games in a small studio, and the stories left to tell.

Never Say the Same Thing Twice: The inkle Magic

Amanda Tien (AT): In all the inkle games I’ve played, there is often a permeating feeling of curiosity, that there’s something interesting just beyond that next door. How do you build in that sense of discovery? Why is it important to have that feeling even if it’s not a “traditional” mystery game?

Jon Ingold (JI): In most games, the player is encouraged to tackle the next challenge because it’s there—either directly in the way, in a mission, or else it’s an unchecked box on the map. That kind of direction makes a lot of design sense and keeps players motivated, but narratively it’s pretty hollow. Why does the protagonist of Elden Ring go around clonking everything in sight? Why does Link think exploring every last cave is going to help him save the kingdom, exactly?

To make it work, you have to start with a world that’s honest and purposefully built—yes, there is something behind that door or over that hill, and it also makes sense in the narrative, that it’ll help you. It’s not just another loot drop point. Then you have to foreshadow and drop hints to suggest to the player where they might be able to push a little further without knocking over the scenery.

Both Moira (in A Highland Song) and the player want to know what’s over that side of the loch. Both Veronica (in Overboard!) and the player want to know, say, what’s inside the Major’s cabin, because it might help them both to get away with the murder. So, setup and payoff, basically, same as in any mystery story in any other medium!

AT: I called Overboard! my favorite “reverse detective” game because you’re playing the bad guy. What delighted your team about making Overboard!, especially in comparison to your other releases?

JI: The most delightful thing about Overboard! for us was its sheer existence. The game started as a moment of inspiration for the opening of a visual-novel-like game, and was ready to ship 100 days later. It came together super fast, the way only a really fun idea can. The second most delightful thing was releasing the game entirely by surprise and giving our players the same feeling of a bolt from the blue.

AT: In Overboard!, getting to know other character’s routines and motivations is key to getting away with the crime. I’m always impressed with how tangible the characters feel in your games, even if they’re only in passing. I’ve replayed 80 Days many times just trying to meet the same people again and again. I came to deeply care for the protagonist of A Highland Song, Moira. What do you think makes a character feel whole/real/tangible in a video game?

JI: The ever-present danger with characters in games is functionality. A character in any story has got to be functional: They have to further the plot, or build out the world, but if they do so at the expense of their humanity then they’re not characters anymore, they’re just the author yelling at the audience. In games, because characters have to be responsive to the player, it’s hard to go the extra mile and make sure they push back, but that resistance is the essence of their humanity. So our characters will always refuse to answer questions, leave before you’ve exhausted everything they might say, and put you on the spot with questions of their own.

We try our absolute damnedest to make sure they never say the same thing twice, too, because then the game is up in an instant, and to help with that, we never let the player farm dialogue trees to their ends. All of that boils down to: We try to care more about the needs of the character than the player, because good characters are worth a little friction, and in fact, it’s in the friction between player and NPC that character comes out.

“It’s in the friction between player and NPC that character comes out.”

AT: They feel like nuanced, like real people. I love that on the inkle team page, you include “alumni” of past employees as well as a list of people you collaborate with. I think it’s a really thoughtful approach, and one that I wish I saw more companies—not just developers—do. And it makes sense that there’s varied collaborators, because every inkle game is pretty different. What has been important to you and inkle to keep in mind with regarding people and culture over the last 13 years?

JI: Thanks for noticing! One of the things we always wanted to do with inkle was use it as a platform to make space for talented people to do great work. When I was in my twenties, I tried a lot of different ways to break into professional writing but could never catch a break—the first time my writing was published professionally, it was in one of our games. So I really wanted inkle to be able to help out people earlier on in that journey.

“The first time my writing was published professionally, it was in one of our games.”

The reality is, though, the economics of independent games are not great, and as inkle’s co-founder Joseph Humfrey and I both have young families, we have a lot less time for mentoring and developing more junior staff, so we’re not doing as much of that as I would like. I hope we can do more in future—but I’m proud of what we have done, and I love collaborating with people, writers especially.

Venturing Into the Unknown With A Highland Song

AT: A Highland Song features Moira going on an epic runaway journey from her small cabin in the hills to a lighthouse by the ocean to visit her uncle Hamish. It’s inkle’s first foray into the platforming genre. What came first: the desire to have a character trek across the hills and lochs, or the “big reason” why she does so?

JI: The landscape came first—Joe grew up in Scotland and wanted to make a game that captured the sense of the landscape, and the scale, and the scenery. For the longest time, we didn’t even know how much narrative content there would be (if any!). The reason for the journey emerged quite slowly as I began working on the project by researching Scottish mythology, but even when I had the idea of it, it still didn’t coalesce until I found the poem that the game opens with: It’s called The Pilgrim’s Aiding.

The idea of Moira as a pilgrim was key for me to understanding the story and its shape and tone. A pilgrimage is a journey you can only take once, because you aren’t the same person when you arrive as when you set out. And then somewhere during writing I realized it was a game about the pilgrimages we all undertake, to greater or lesser extents, as we set out to find out who and what we really are. Some people have to travel a long way before they can begin.

“I realized it was a game about the pilgrimages we all undertake […]”

AT: I admired the well-paced reveals of Moira’s background. How did you choose what information to reveal and when?

JI: Like a lot of inkle’s dialogue, it’s a balance of systems and content that’s quite hard to describe. Internally, we have a script of things Moira can reminisce on: They’re roughly prioritized in terms of their “depth,” and that maps, roughly, to how far through the world you are. The actual triggers for dialogue are various—timers, and geographical contexts, which should balance out in the long run to make her talk “when it feels right.” But the system can be knocked sideways by things Hamish says (in memory), or choices the player makes, should those bring other topics into focus.

I suspect most of that detail is just detail, though, and really it’s the prioritization that makes the game work—starting from Moira’s relationship with her mother, and with the hills, moving outward to talk about Hamish, and her brother, and then closing in on her doubts, uncertainties, and questions about herself… That’s roughly how therapy goes, isn’t it?

AT: [laughs] Accurate. Moira’s journey is largely a lonely one, which makes those moments of confiding with the player all the more powerful and impactful. That being said, I was delighted whenever Moira ran into someone, and I always took time to talk to them. Do you have a personal favorite NPC?

JI: Great question! I enjoyed writing the geologist; researching something specific you know nothing about always turns up gems, and I loved the detail that Scotland was originally an independent landmass. The woeful giant was another highlight, mainly because I’ve no idea where he came from; he just started talking that way. I can’t really justify it, but I found it very atmospheric and mournful and not just, y’know, weird.

For the longest time, the ice climber in the cave was completely generic, with a note in the script that said MAKE THIS LESS SHIT. It was a good and reassuring day when I finally sat down and gave him an actual voice. But my favorite character is the spelunker. Spelunkers are completely bonkers. And it was a treat seeing the reaction of the team when they met him for the first time.

AT: You’ve done a lot of interviews and features on A Highland Song (yay coverage, including with The New York Times!). You’ve gotten to talk a lot about the amazing music in the game, especially syncing the rhythm-based portions with partnered folk groups like Talisk. Is there anything that you’ve wanted to share about the game or the process that you haven’t yet?

JI: I don’t think I’ve really had the chance to rave about the actors anywhere. We cast MJ Deans as Moira years ago, for our first teaser trailer, and even that first simple recording session was such a formative experience for me as the writer—Moira’s voice was grounded by those early sessions, and they took her from being a hypothetical character to a living breathing person, capable of much more range and wit and emotion than I’d originally thought possible. We even recorded a Gaelic song, which is beautiful (but you have to work to find it in the game!).

I love working with actors; they’re like dynamite under the script. Later, we cast Paul Warren as Hamish—it was a blind casting process based on recorded samples only, and we loved the gravelly depth and warm emotion of his recording. Then when I finally met him over Zoom I got the biggest shock: He’s a really young man, with a boyish face. He popped up on screen and I thought, “Okay, but is your dad in?” And then he starts reading the lines and the world-weary fisherman is right back there. It’s just magic; recording sessions always put a ridiculous smile on my face.

The other wonderful part of the game was the level design. We’ve never worked with a level designer before and Nat Clayton did an amazing job of laying out these mountains that feel real and properly scaled, but are full of detail—and above all, can be tackled in any direction. People are often so busy getting lost in the mountains they don’t realize how astonishing it is that they never get stuck!

An Island in a Hurricane: A Small Studio in the Current Industry

AT: 2023 was a rough year for gaming developers with widespread lay-offs, continued crunch, and company culture problems. What are some ways you’d like to see the industry evolve?

JI: Ultimately, the mainstream industry doesn’t interest me much as a player or a designer—I don’t see an enormous amount of new ground being broken, just more and more specialization within existing designs. That’s fine for the players who are happy in those genres, but it doesn’t widen the pool or bring in new people. You often hear game designers bemoaning how games are still not considered proper art, but here we are working in a discipline where you require specialist knowledge and/or hardware to even *buy* a game, let alone find it, understand it, or enjoy it. There was a brief period when good premium games on mobile were feasible and that was incredible—we could make games like 80 Days and put them into the hands of people who had no games literacy whatsoever—but that moment has passed. Steam is massive, but utterly insular: My parents will never create Steam accounts. The Switch is the closest thing we have to an “open” games portal.

“There was a brief period when good premium games on mobile were feasible and that was incredible […] but that moment has passed.”

And I don’t know how any of this gets solved. Even if better distribution channels open—say Netflix gets their games arm up and running, cross-device, or Microsoft bundles Game Pass into Windows in some super-direct way—as soon as that happens, the large publishers will swamp those channels with high-marketing, low-cost-to-entry releases. There’s simply too much money to be made in games for indies to be given a viable platform unless it’s deliberately curated.

AT: I appreciate the reference you just made to your parents and Steam, actually. Early in the pandemic, I worked hard to get my mom into video games and later wrote a guide to help others—80 Days was how I got her hooked! What does inkle do well (perhaps because it’s a small studio) in the face of these struggles?

JI: Honestly, inkle survives by the stupid and simple solution of being small—we’re three people full-time, with another five or six people on contract depending on what’s going on. We make enough money from 10 years of releases that we don’t need to get external investment, so we’re not at the mercy of publisher’s schedules or investors’ angst. No one makes us put AI or crypto features into our games, and we get enough time to think about what we’re doing.

But on the other hand, we’re always doing the streamlined version. It’d be nice to do something bigger, and more ambitious, with more polish and more juice—the kind of project that takes 20 people, or 30—but the sales we see are never so big that such a venture doesn’t feel like commercial suicide.

So, we survive, and I’m incredibly grateful for that, because I see indies both promising and successful shutting up shop all around us, but I don’t see us able to absorb any of that talent, and that makes me sad.

AT: What’s next for inkle?

JI: Quite honestly? Dunno. For the first time in 10 years, we don’t have our next project in the stables ready to go. Personally speaking, I’m doing some freelance writing for other people’s games, and finishing up a novel for my agent. But something inkle-shaped will come along, it always does, and I can’t wait to meet it.

Amanda Tien (she/her or they) loves video games where she can pet dogs, solve mysteries, punch bad guys, play as a cool lady, and/or have a good cry. She started writing with The Punished Backlog in 2020 and became an Editor in 2022. Amanda also does a lot of the site's graphic designs and podcast editing. Amanda's work has been published in Unwinnable Monthly, Poets.org, Salt Hill Journal, Aster(ix) Journal, and more. She holds an MFA in Fiction from the University of Pittsburgh. Learn more about her writing, visual art, graphic design, and marketing work at www.amandatien.com.