Understanding Why I Like (or Dislike) the Games I Do

Disclaimer: This will be the most self-indulgent thing imaginable.

I love The Witcher 3, but don’t like Dragon Age: Inquisition. I can’t get into most JRPGs, but I kind of like Paper Mario: Sticker Star. I’m a huge Legend of Zelda fan, but I’ve never loved the original. The Super Nintendo is my favorite console ever, yet I don’t think I’ll ever finish Super Mario RPG or Super Metroid. My favorite genre is probably 2D platformers, yet I can’t say I truly care for the Mega Man games. I despised the Assassin’s Creed series until it added RPG elements, but I like Fallout 3 more than its predecessors because it scales down some of the RPG stuff. I can’t get into XCOM, but I’m more than happy to replay the entire Banner Saga trilogy at the drop of a hat. I put a hard cap of 35 hours into Skyrim, yet I know I’ll log at least 200 hours into Super Mario Maker 2 when it comes out.

Why am I like this?

People tend to believe they understand what things they like and don’t like. They know they prefer pizza to hamburgers. They know whether they’d rather have a partner who likes to party and have fun over one who prefers watching reruns of Friends all the time. They know they like the Marvel movies over the DC ones, but prefer the actual DC comics. If you stopped anyone, however, and simply asked them why they like what they like, how would they answer? Have they thought about this before? Would it cause them to second-guess their preferences if they dug deeper into the recesses of their own minds?

Obviously, there’s a larger discussion to be had on the nature of preference, but for now I’d like to focus on my own predilections when it comes to gaming. Barring a handful of exceptions (I’ve never liked MMOs or RTSs), my taste in video games is largely inconsistent if you view it purely through the lens of genre. I wouldn’t say I like/dislike RPGs anymore than I like/dislike first-person shooters, and I wouldn’t say I particularly dislike tactics-based games, even if I don’t play many of them. I also don’t think it’s true that I favor certain game developers/publishers over others. While I tend to love Nintendo-made games more than anything made by anyone else, that favoritism largely extends to a handful of franchises, e.g. Mario, Zelda, Smash Bros., and Donkey Kong. On the other side of that coin, I hardly ever play the Kirby games, I’ve yet to encounter an Animal Crossing title that grips me, I don’t love Metroid, and I’ve passed on more Pokémon games than I’ve actually played.

This essay could be yet another meandering thinkpiece that doesn’t come to any concrete conclusions, but instead I’ll actually pick a handful of examples from which I can mine for answers. As an exercise, I will select five pairs of games that fit into roughly the same ludo-category (and, for consistency’s sake, come from the same era) and try to determine why I prefer one over the other. Hopefully, if all goes as planned, I will emerge from the other side with a firm set of reasons why I like the games that I do.

Example 1: The Witcher 3 vs Dragon Age: Inquisition

What they have in common: Both are large, open-world fantasy role-playing games that helped ignite interest in the current console generation, which was still relatively nascent when both of these games launched. Each places a premium on player choice, including multiple romancing options, political intrigue, and scores of sidequests. Whichever one you choose to play will have swords, magic spells, enormous monsters, elves, and highly-adorned castles.

Where they differ: Much like previous entries in the series, Inquisition’s combat is team-based, with players able to select which party members will accompany them on various journeys and to determine what battle tactics to employ should any fights take place. Meanwhile, The Witcher 3 is a purely solo experience, where the player has no fealty to anyone but themselves, even though Geralt of Rivia, a defined character, has relationships with other people in the game that are based on previous experiences. Inquisition allows for more customization when it comes to character creation, while The Witcher has a few narrative limitations.

In addition (and this might be a point in favor of Dragon Age), Geralt’s main relationship opportunities are based on lore that ties to previous entries in the franchise (including the books from which the world and characters are adapted), meaning the player can’t engage in any romance-based gameplay from an outside perspective. Meanwhile, Inquisition allows the player to get down with any number of characters with no historical ties to the protagonist and even includes same-sex options. While this may seem like just one small point of difference between the two games, RPGs are about imprinting your own personal choices on a largely predetermined narrative, and the humanizing nature of love and sex often plays a central role in the development of a character in just about any story.

Why I prefer The Witcher 3: Unless a game utilizes turn-based combat mechanics, I typically prefer to only control one character at a time. Part of that is because real-time team systems are often clunky and confusing, but in the case of TW3, it helped me gain a better understanding of the character; Geralt’s sword swings and lunges feel akin to a beautiful dance, and the way I mix in signs (the game’s form of magic) all comes together rhythmically. Meanwhile, battles in Inquisition often just feel like roadblocks: a way for the game’s fantasy elements to appear on screen in between conversations and exploration.

Speaking of conversations, The Witcher 3 has some of the most compelling (and convincing) writing and voice acting of any game I’ve ever played. Geralt’s relationship and interactions with friends, adversaries, enemies, and sexual partners all feel fully earned, as even callbacks to previous games are explained in ways that feel organic and not ham-fisted. In Inquisition, however, much of the dialogue options are designed to feel like gameplay options, where it’s clear how many different paths I can take, even if I don’t think any of the paths are that interesting.

The biggest difference between the two games, in my view, is that The Witcher 3’s side quests never feel like padding. Every single quest has a miniature story with layers and complexities that elevate the experience to more than just a grindy game of fetch. Dragon Age may have the more appealing broad fantasy narrative, but every side quest I attempted in that game just felt forced and pointless, like I was doing them just because I needed something to do and didn’t want to progress in the game too quickly.

What does it all mean?: Whenever someone asks me why I love The Witcher 3 so much, I always say something along the lines of, “It respects me and respects my time.” Open-world RPGs have a tendency to stuff themselves with hundreds of additional missions and opportunities to make everything feel more alive, but often these experiences are forgettable — just a way for you to reach that 100-hour threshold that allows you to feel like you’ve done all you can. The Witcher 3 doesn’t do this; it makes sure every interaction feels carefully crafted and that even the most robotic-looking of NPCs feel real and worthy of your time.

The Witcher 3 helped me realize why I haven’t always embraced RPGs and why I usually prefer more focused open-world experiences like Zelda: because I truly value my time and never want to spend even a couple of hours with something and feel like I’ve accomplished nothing of substance.

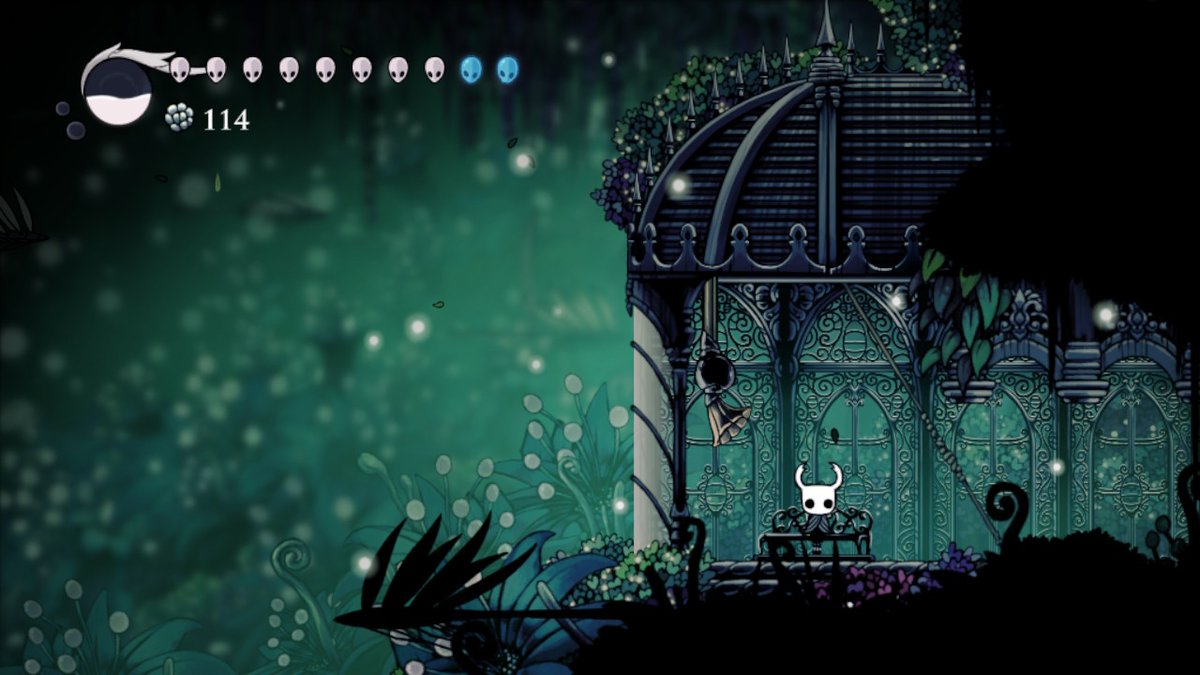

Example 2: Hollow Knight vs Dark Souls 3

What they have in common: Both are non-linear action-RPGs with limited explanations as to what you’re actually doing. Each one has harsh consequences for failure, but both are built so that the player can find different ways to progress. Also, both are quite literally dark, at least in terms of art direction.

Where they differ: Obviously, Hollow Knight is a 2D sidescroller while DS3 is a massive, open-world 3D experience. Also, Souls leans much more heavily on RPG mechanics and customization, while Hollow Knight instead gives you a defined character with various charms (e.g. abilities) you can play around with, but not a great deal more than that.

Another key difference: While Hollow Knight is certainly difficult, the ability to move around more swiftly (as it is also a platformer) removes some of the constant dread that accompanies FromSoftware games, where often you can see your impending doom from a mile away and can do very little about it.

Why I prefer Hollow Knight: Simply put, Hollow Knight is easier, almost entirely because of basic quality-of-life features. Being able to easily escape from enemies with excellent platforming mechanics, as well as having the option to heal without a draconian system like limited estus flasks, allows me to feel more immersed within the world and notice all the beautiful details it holds. Sure, I died a whole bunch against some of the tougher bosses (and even some of the easier ones) and found myself frequently lost in the game’s labyrinthine tunnels and caverns, but Hollow Knight’s worldbuilding, controls, and systems never made failure demoralizing.

Meanwhile, I reached a point in Dark Souls 3 — the game in the series I’ve played the most — after about 13 hours where every single moment just felt like hell. I wasn’t able to “git gud” quickly enough, and I felt like any attempt to find a new path or new strategy would end with me losing progress. Even when I was able to persevere and move past particularly challenging sections, I never actually felt like I accomplished something, but rather just survived it. The whole experience left me deflated and, honestly, like I had wasted my time, which I believe is the worst possible thing you can say about a game.

What does it all mean?: Had I tried any of the Dark Souls games when I was in college (or when I was unemployed), I would probably have found some way to appreciate them more and really give them a fighting chance. The reality is that my time is more valuable to me than ever, and I just can’t make room in my life for the demands of a video game that is fundamentally designed to beat me down constantly for dozens of hours. There’s a fine line between difficulty and torture, and Hollow Knight falls on the right side of that line.

Example 3: Chrono Trigger vs Final Fantasy VI

What they have in common: Both are Square Soft-made JRPGs for the Super Nintendo with turn-based combat, epic storylines, and iconic music and characters.

Where they differ: Other than their obviously different stories, Final Fantasy VI includes random encounters, while Chrono Trigger displays nearly every possible enemy onscreen to be challenged at the player’s discretion. Additionally, FFVI takes the player to a separate screen for battles, while Chrono Trigger’s battles and travels occur within the same frame.

Why I prefer Chrono Trigger: Honestly, there’s a real chance that I find Final Fantasy VI’s story more compelling than that of Chrono Trigger, but I wouldn’t know because the constant random encounters killed any sense of immersion I was supposed to experience. Sure, many RPGs survive on the concept of random encounters in an effort to declutter an otherwise vibrant world, and you know what? I don’t like any of those games. Even Pokémon gives you the option to simply walk around tall grass (though you’re kind of boned when it comes to caves and water sources).

Nothing else about Final Fantasy VI really bothered me all that much, and I was enamored with its world and characters for the brief time I tried it. But while it may seem petty and shortsighted to give up so soon because of a single mechanic (also, to be fair, I didn’t find the turn-based mechanics all that enthralling), random encounters are a core tenet of the game — something you can’t really avoid if you want to proceed with the story. Chrono Trigger never made the basic traversal of its lands a chore, and that alone would make it the superior experience for me even if Final Fantasy bested it in all other areas.

What does it all mean?: As I said, a single mechanic can indeed ruin an otherwise great game for me, and given the presence of YouTube Let’s Plays, I can experience stories in other ways. It might appear unfair, but I don’t believe it is; games, especially RPGs, ask a lot of the player, and I don’t want to commit to something that will frustrate me every ten seconds.

Example 4: Super Mario World vs Mega Man X

What they have in common: Both are iconic SNES platformers released early in the console’s life cycle that greatly built upon each classic series without forgetting their respective roots.

Where they differ: Well, I guess one is more of a shooter? Beyond that, Mega Man X has a small number of detailed, difficult levels and is meant to be completed in a single playthrough. Meanwhile, Super Mario World focuses more on running, jumping, and even flying, and has tons of levels, including dozens of little secrets.

Why I prefer Super Mario World: It would be easy for me to say that I just prefer Mario games over Mega Man games, but in this case, I think it’s a little deeper than that. Whenever I go back and play Super Mario World, I find new things to appreciate about it, such as certain animations, the cleverness of some of its levels, and how wild it is that you basically can’t get to the final stage without actively looking for secrets. In many ways, it feels decades ahead of its time, and its excellent controls, charming music, and clean 2D visuals make it a game that could be enjoyed in any era.

On the other hand, as good as it is, Mega Man X plays like a game very much of its time, not ahead of it. The game’s reliance on passwords to “save” progress, limited lives, and questionable hit detection make it a fun relic to return to every now and then, but not something a newcomer would appreciate all that much. After replaying it recently, I don’t see why Mega Man X is still discussed alongside games like Super Mario World when people rank the top games on the SNES. Frankly, I would put it more in the category of Super Star Wars and X-Men: Mutant Apocalypse: games that were great for their time but have become somewhat obsolete due to basic advancements in the medium.

What does it all mean?: Some games hold up better than others, and in some cases you need to have tried something when it originally released to really understand its impact. In the case of Mega Man X, I can’t play it like it’s a modern game; I just can’t. Not when Super Mario World still feels fresh 28 years later.

Example 5: Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus vs Doom (2016)

What they have in common: Both are Bethesda-published cinematic first-person shooters where you gun down enemies while you’re running towards them. Both are extremely graphic and include some of the most brutal takedown animations in any modern AAA game.

More importantly, the rebooted Wolfenstein and Doom games all carry the weight of their forefathers, which established the roots of the FPS — in many ways the most popular game genre. While the newer titles obviously can’t be as innovative, they are just as thrilling, maintaining the respective ethos of their predecessors while adding just enough interesting twists to stand up on their own.

Where they differ: Notably, Doom’s story is largely just an excuse to justify why you’re sprinting through some hellscape firing lead into scores of demons. Meanwhile, the newer Wolfenstein games are much more story-focused, telling a harrowing tale of what the world would be like had the Nazis gained better weaponry and conquered much of the Western world. Also, Doom handles a little better as a pure shooter, with quicker and more precise controls, while Wolfenstein places a premium on stealth and silent takedowns (though there is plenty of carnage to be found).

Why I prefer Wolfenstein II: When I first tried Doom about a year after it launched, I found the experience lacking in substance. Sure, I’m not against the occasional plotless button-masher, and I don’t need every game to have a thoughtful story. It just felt like Doom barely even tried, and as a result the endless shooting gallery began to feel stale after a few hours. It was fun for a little while, but I never felt like there were any stakes.

When I played Wolfenstein II for the first time, I was completely hooked. The action sequences were just as thrilling as those found in Doom, but I felt more personally attached to our hero, B.J. Blazkowicz. His internal monologuing brought me into his tortured mind, and even the briefest of conversations and interactions with other NPCs made every relationship feel real and honest. Additionally, the Nazi imagery in the United States was poignant and timely, as the rebirth of Nazism in America (as well as the politicians and journalists that enable such dangerous ideologies) over the past few years made all of this seem within the realm of possibility, save for maybe the military base on the planet Venus.

What does it all mean?: Wolfenstein II was not merely another solid AAA shooter for me; it was an emotional experience, one that I admire and treasure despite some of the game’s messy tonal issues and mechanical shortcomings (seriously, the hit detection in this game needed some work). While Doom might be the “better” game from a systems standpoint, it never felt like anything beyond a modern reimagining of the kind of mid-90s shock value that made the more culturally conservative members of society clutch their pearls. Wolfenstein II might be nearly as gory, but it at least gives that violence some measure of purpose.

CONCLUSION

Based on what I’ve written above, I have come to the following three takeaways:

- I have little patience for games that don’t respect me and my time.

- As much as I enjoy classic titles, certainly quality-of-life advancements have made it so that certain older mechanics (e.g. passwords and random encounters) nearly ruin the experience for me.

- Challenging games are welcome, so long as difficulty doesn’t end up being the defining aspect of the experience, at least of what I’ve played.

I probably could have told you all of that before making all these comparisons, but the more I think about it, the more sure I am in the stated principles. Typically, it’s difficult for me to explain all the finer details that would lead me to say Gears of War 2 is one of the best games of its generation while BioShock is not, but I do know that some of these broader takeaways ultimately determine whether or not my experience with a game is positive.

All that said, I’m not sure I’ve actually made it very far in this exercise, as I’ve ended up raising more questions than I’ve answered. I’ve explained why much of the torturous exploration of Dark Souls 3 turned me off from the experience, but I’m struggling to really say why I believe Hollow Knight does it better. I’ve decried Mega Man X for failing to meet modern quality-of-life standards, but then again I have no such complaints for the original Super Mario Bros. And honestly, I could probably write a book on why combat in The Witcher 3 is good, actually, but I didn’t do much of that here. Maybe all of this was a waste of time.

Still, these self-indulgent manifestos I occasionally engage in are good for me, if not for any readers, because they fundamentally help me understand more about myself as a person. For the longest time, I just played what seemed fun to me without a conscious understanding of why I preferred certain experiences over others, but nowadays I approach every single game with a critical eye. As a result, I know that my time is more valuable to me now than it ever has been, that I often have to view politics and social mores through a more modern lens than before, and that there is a fine line between challenge and hardship. While they are not the chief instigator of such changes in my way of thinking, games have assisted in my personal evolution. That is why I continue to play them, and why I continue to write about my relationship to them.

Self-indulgence over.

Sam has been playing video games since his earliest years and has been writing about them since 2016. He’s a big fan of Nintendo games and complaining about The Last of Us Part II. You either agree wholeheartedly with his opinions or despise them. There is no in between.

A lifelong New Yorker, Sam views gaming as far more than a silly little pastime, and hopes though critical analysis and in-depth reviews to better understand the medium's artistic merit.

Twitter: @sam_martinelli.