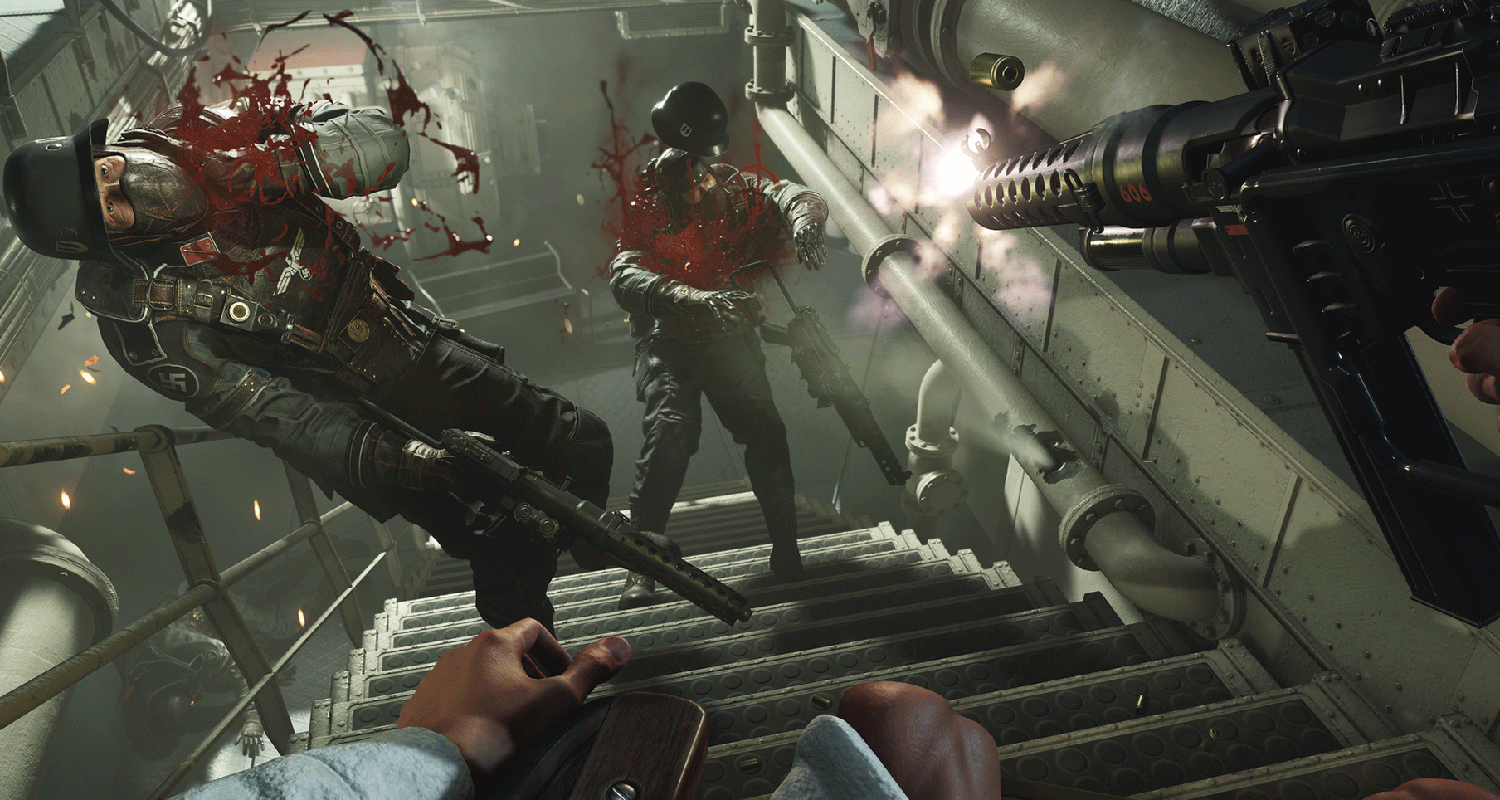

The most jarring scenes in Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus, Bethesda’s latest Nazi-shooting sim, occur not during bloody firefights, brutal executions, or in the midst of a completely obliterated New York City. They occur in moments that appear otherwise ordinary.

(spoilers ahead)

The New Colossus Shows a World in Which Nazism is Normal

The latest Wolfenstein game takes place in 1961, in an alternate history where the Germans won World War II and conquered the United States by creating a wide array of high-powered weapons, armor, vehicles, and robots made from futuristic alien technology that they discovered after a portal exploded (bear with me here). Protagonist B.J. Blazkowicz, an American Jew from Mesquite, Texas, has joined a resistance group hell-bent on overthrowing the new Nazi regime in the U.S. and ending the reign of the Third Reich once and for all. What follows is an experience with crazy tonal shifts, ranging from scenes of horror and shock to ones of jokes and action movie one-liners.

Obviously, the Nazis taking over America and installing their own beliefs and policies on the so-called “Land of the Free” should be shocking enough on its own, and the brutality with which every armored Nazi on screen treats any resistors should rattle anybody to the core. These images, however, didn’t appall me too much, as the Nazis are clearly the enemy in this game, and video games typically go out of their way to characterize villains as the root and epitome of all evil. Also, in a sense, I’ve been desensitized by extreme violence in the medium. What shook me (and nearly brought me to tears a couple of times) was just how accepted and normalized Nazism had become in this alternate universe.

Take, for example, B.J.’s trip to Roswell, New Mexico, where Good Americans (the new Good Germans) have gathered to view a parade for Nazi military leaders, showering them with praise and joy often reserved for football players who just won the Super Bowl. Ambling through Roswell’s streets, you witness Nazi propaganda strewn across buildings and telephone poles, reminding you that the teachings of the Third Reich now encompass every inch of American life. At one point, you pass by two men robed in Ku Klux Klan garb practicing their German with an armed Nazi soldier (this scene also shows that such racist ideology did not originate in Hitler’s mind or on European soil).

Despite the presence of such horrors, the city and its residents don’t appear too fazed about anything. You see mothers shepherding their children to their cars, people waving to their neighbors amiably, customers patronizing a local diner, and moviegoers waiting in line for the next big cinematic hit. The people of this New Mexican city have fully accepted the consequences of Nazi rule and live their lives as though everything was fine. As though this was all normal.

Similarly chilling imagery appears throughout much of Wolfenstein II, depicting an America that has reconciled with (and largely embraced) the law of the swastika. After his capture midway through the story, B.J. Blazkowicz attends trial in an enormous courtroom (presumably in Washington, D.C.) with red Nazi flags everywhere. In this scene, an American judge sentences B.J. to death for his “crimes against the state,” though the “state” is not one Blazkowicz recognizes at all. In a covert operation where Blazkowicz heads to a Nazi stronghold on the planet Venus to audition for a movie role while undercover (yes, you read that right), an aging Adolf Hitler asks all the actors if they’ve read his book (presumably Mein Kampf), and one man with a clear American accent zealously answers, “Yes, Mein Fuhrer, and my children have, too!” Meanwhile, the player also witnesses first hand the aftermath of the destruction of American havens of diversity, as Blazkowicz must pass through Manhattan after its nuclear obliteration and New Orleans after it has been transformed into a hideous ghetto.

It’s one thing for the U.S. Military to be overpowered by a Nazi regime armed with the most advanced weaponry imaginable, and it’s one thing for Americans in such a scenario to fear resisting, lest they lose their lives in the process. It’s another thing entirely, however, for Nazism to become the new normal with seemingly little resistance. Wolfenstein II shows that, when faced with an overwhelming force of violence and hatred, there’s a solid chance most white Americans just go along with it, having learned nothing from the atrocities non-white people have suffered throughout this nation’s history.

Just How Different is the Real World?

As a Jew, seeing the Nazi-ruled dystopia of Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus was especially harrowing. While I may not know much Hebrew and I haven’t fasted for Yom Kippur since 2011, I still consider Judaism to be an essential part of my identity. I may not look stereotypically Jewish, but I know that if the Nazis ever come to get me, they won’t care about the size of my nose or the curliness of my hair, nor will they pay much mind to my lack of religiosity; I’m still a filthy Jew to them, same as all the rest.

I’m lucky to say that I haven’t experienced the same level of anti-semitism that has plagued my people for eternity, but I’ve always known that the horrible racists who want to cleanse the world of non-whites were out there lurking in the darkness. Over the past year and change, such cretins have emerged from the shadows and into our political rallies, social demonstrations, and Twitter feeds, ready to blame everyone but themselves for their problems.

What kills me is that so much of this neo-Nazi fervor has been met with shrugs or even calls for empathy. We have a president who fails to condemn White Nationalist rallies. We have popular websites referring to alt-right leaders as “dapper.” We see people online calling for an end to “political” discussions about neo-Nazis, when such matters should be non-partisan. We’ve even seen the New York Times, known widely as a beacon of journalistic integrity, publish milquetoast, puffy garbage that attempts to paint neo-Nazis as just regular Americans who are weighed down by “economic anxiety.” And yes, I acknowledge that this rise in ethno-nationalism and white supremacy has been met with harsh criticism and condemnation by many Americans, particularly many in power. It just hurts that such condemnation isn’t universal.

Getting back to video games: Wolfenstein II is mostly an absurd meta-historical bullet storm peppered with insane pseudo-science and dialogue taken straight out of an 80s Stallone movie. Virtually nothing about the game is realistic, except for the idea (nay, the fact) that, in the face of rising Nazism, many would roll over and/or fully embrace the new world order and view their captors as people with “differing views of the world.” Much like in the real world, many inhabiting the world of Wolfenstein II see the denial of my right to exist as merely a different opinion.

The events of The New Colossus take place in 1961, and given the alacrity with which the Germans eliminated as many Jews as they could, one could assume that nearly all Jews in the game’s alternate reality have been killed. It pains me to see even a fictional world where that has happened; it kills me even more to think of how close that was to being a reality. If enough people respond to an influx of Nazism with indifference, we might not be too far from such horrors.

Don’t let this be normal.

Sam has been playing video games since his earliest years and has been writing about them since 2016. He’s a big fan of Nintendo games and complaining about The Last of Us Part II. You either agree wholeheartedly with his opinions or despise them. There is no in between.

A lifelong New Yorker, Sam views gaming as far more than a silly little pastime, and hopes though critical analysis and in-depth reviews to better understand the medium's artistic merit.

Twitter: @sam_martinelli.