Lara Croft Is Back in Business

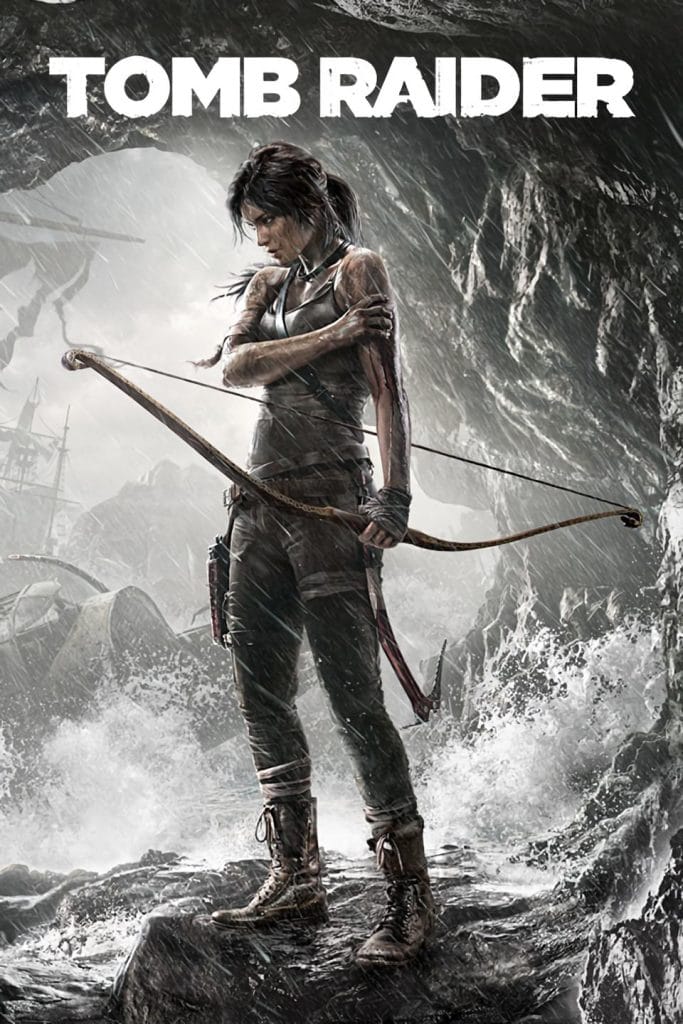

For the first time in a while, it’s a good time to be a Tomb Raider fan!

The 2025 Game Awards unveiled trailers for not one, but two separate Tomb Raider projects. The first was the reveal of Tomb Raider: Legacy of Atlantis, a remake of the original 1996 Tomb Raider, set for release in 2026. The second was a brand-new game, Tomb Raider: Catalyst, aiming for a 2027 release.

Amazon dropped a costume test of Sophie Turner as Lara from the long-gestating Phoebe Waller-Bridge television series a few weeks ago, dominating headlines (or at least my Twitter feed). The second season of the Netflix animated series The Legend of Lara Croft was also released two months ago to less fanfare but a significantly warmer reception than the rather milquetoast first season.

Given that a mainline entry in the series hasn’t been released since 2018’s Shadow of the Tomb Raider, the last several months have been a veritable deluge of announcements that have broken a near-decade of franchise dormancy.

From a timeline perspective, Tomb Raider: Catalyst is set years after the events of Tomb Raider: Underworld, with the reboot trilogy serving as her origin story, so we’re seeing a more experienced Lara Croft. But what’s important to know is that this is a new chapter in Tomb Raider.

– Will Kerslake, Game Director at Crystal Dynamics (via GamesRadar+)

Lead developer Crystal Dynamics has confirmed that Catalyst is set after the events of Tomb Raider: Underworld, with the events of the Survivor trilogy (Tomb Raider, Rise of the Tomb Raider, and Shadow of the Tomb Raider) still serving as her origin story. Now that it’s official that our Lara — at least for the foreseeable future — is incorporating both the Survivor and Legend timelines into a unified vision for the character, it feels like as good a time as any to take a retrospective look back at the Survivor trilogy.

A “Controversial” Reboot

If I were a betting man, I would have bet that whatever Crystal Dynamics chose to do with Tomb Raider, it would be a fresh start, untethered by any of the games that came before. The Survivor trilogy was undoubtedly a success, but it also comes with associated baggage.1 Some of the criticisms directed toward the trilogy I’m willing to categorize as bad faith — I’m lumping any homophobic complaints or commentary on her body type in that category — but others are more genuine.2

It’s undeniable that the Lara from the Survivor trilogy is a fundamentally different character from her previous incarnations. The Lara from the first six games and the Lara from the Legends continuity differ slightly in the details but largely share similar dispositions and characterization; in contrast, the developers actively set out to create a wholly different version of Lara with the reboot.

In some way, [Lara] had gotten to a point where she was so powerful, so rich, so accomplished, that she could never lose, she could never fail, and similarly, people sort of identified her in a very… surface way, that she was dual-pistoled and in a braid.

– Noah Hughes, Creative Director at Crystal Dynamics (via IGN Middle East)

Rebooting a character is inevitably damaging. Most things in reality tend to be zero-sum; reimagining a character means you risk losing fans of the previous incarnation. The reboot successfully returned Lara Croft to prominence, but sidelined the old Lara for nearly two decades, which isn’t something that’s lost on me. I would imagine that for many younger fans, their image of Lara is not the sassy, witty, brave, and confident adventurer version of Lara at all. To see the perception and mainstream image of a character you love shift underneath your feet to something else can be a bitter pill to swallow, especially when you know those two versions aren’t likely to coexist.3 See the introductory cutscene from Legend as an example of what this chronology’s Lara is like:

Lara was suave, smooth, snarky, witty, collected, and confident. Obsessed in some ways, and highly determined, which are traits both versions share, but that’s about where it stops. Our introduction to the Survivor trilogy’s Lara depicts a woman who doubts herself, who is sexually assaulted by a man, abused in a myriad of ways, and is fetishized by the camera as a victim.4

The combination of setting and tone of the reboot locks her in as a character who is then defined by committing egregious amounts of violence and murder in a vaguely justified way. It was a huge departure, and it’s not hard to see why fans of her former chronology were disappointed. It really was difficult to imagine this Lara becoming the character from Legend and beyond.5

It isn’t constrained just to a character problem: There’s a tonal incongruity between the Survivor trilogy and the other games in the series as well. I find the consternation from long-time fans regarding these changes justified, and it seems the pendulum is swinging back toward the characterization and tone of the earlier games in the series in the “Unified” timeline.

Personally, I’m very intrigued to see how Crystal Dynamics will resolve these incongruities (if they intend to at all, as forcible retcons are a time-honored tradition in reboots). Insofar as this unified vision of Lara will contain the multitudes of her chronologies, now seems as good a time as any to do a deep dive into the character of Survivor Lara, who diverges so notably from her previously established counterparts.

Finally, I want to preface this analysis: I love Tomb Raider and Lara Croft, and both are near and dear to my heart. Both iterations are valid and have their pros and cons, and my analysis going forward comes from a place of love and a desire to see even more interesting, awesome adventures going forward. The more I like something, the more I have to say about it!

We’ll start with Tomb Raider (2013), and how its framing as a pseudo-slasher film sets the stage for much of the character of Lara in the trilogy to come.

Tomb Raider Through the Lens of a Slasher

One of the early development prototypes for what would eventually become the first entry in the Survivor trilogy was a project internally dubbed Tomb Raider: Ascension. Conceptualized as a survival horror game, the description of the YouTube video showcasing its concept art describes it as “closer to a horror game than a Tomb Raider title.” The video displays concept art of Lara fighting off misshapen, ent-like creatures, grotesque quadrupedal monsters, oni from Japanese mythology, and other supernatural horrors:

While this concept was ultimately scrapped, Ascension’s horror roots clearly carried over to the final product. Tomb Raider borrows heavily from horror film conventions, in particular those of the slasher film. These elements can be seen in the overall structure of its plot, the conventional tropes applied to its cast of characters, prevalent themes, and its aesthetic and stylistic choices.

Moreover, I would argue that many of the narrative criticisms lobbied at Tomb Raider — particularly in relation to its ludonarrative dissonance6 — can be attributed to how the game separates itself from slasher conventions. Video games and films are different narrative media, and Tomb Raider’s inability to resolve those conflicts is the source of much of the narrative strain that players experience throughout the story.

What exactly is the framework of the slasher film? Carol J. Clover’s Men, Women, and Chain Saws (1992), a seminal text of film criticism as it relates to the genre, lists several: the Killer, the Terrible Place, Weapons, Victims, and the Final Girl. To summarize more narratively: A slasher film features a group of individuals, typically in some sort of unfamiliar place, being hunted down by a single killer. This killer is typically superhumanly resilient, and their methods of killing are gruesome and violent, with victims being run down one by one until one character remains, culminating in a cathartic and climactic showdown with the Final Girl, the stalwart, plucky survivor.

Some of these elements map smoothly to Tomb Raider; others, admittedly, do not. On a plot level, the similarities are apparent: The crew of the Endurance crash-lands on the island of Yamatai (the “Terrible Place”); members of the crew are killed one by one (our cast of Victims); and there is a brave, plucky, and more self-aware character (Lara Croft) who the player-audience can instantly identify as our protagonist and the Final Girl. After a series of harrowing encounters, Lara faces off in a climactic battle with the Killer, the Sun Queen Himiko, and barely triumphs.

Beyond superficial narrative elements, Tomb Raider also aligns itself with numerous other stylistic and thematic conventions of the genre. As is often noted by feminist critics of slasher movies, there is a gendered nature to victimhood and murder in these films.7 To summarize: Men die quickly, women die voyeuristically. Numerous victimized deaths are peppered across Tomb Raider’s dozen-ish-hour runtime: Early in the proceedings, various unnamed crew members of the Endurance — all male — are summarily executed or dispatched by cultists, typically by a clean shot to the head from a pistol.

Every other named character that is killed is male, and their deaths are hardly a spectacle of blood and gore. The camera pans away as Grim, the ship’s helmsman, is pushed off a large cliff, presumably to his death. The erstwhile tech-head of the crew, Alex, is killed in an off-screen explosion. The infuriating Dr. Whitman is given a violent death, but even here the camera pans away, though the implications of his death are grisly, given his screams. Roth, Lara’s mentor and father figure, takes a throwing axe to the back and dies a heroic death in Lara’s arms.

No other female characters die, at least canonically.8 But there is the elephant in the room: Lara dies. Lara dies often, Lara dies gruesomely, and she dies voyeuristically, screaming in horror or pain, arms flailing in desperation before she expires.

The slasher roots of Tomb Raider are on clear display here: Errant branches brutally stab Lara, and she dies with her arms scrabbling at the punctures in her neck, blood gurgling in her throat. She suffers all sorts of horrific deaths: She is crushed, drowned, stabbed, and bludgeoned. That the victims in a slasher film will be degraded in the eyes of the audience is, in some ways, a given. To see that applied to our Final Girl, the character whom the audience is ultimately supposed to root for, feels greatly counterproductive and disempowering. Altogether, these factors ultimately produce a strange, dissonant sensation as Lara’s status oscillates between being the hero of our story and an object of voyeuristic brutality.

It’s an inevitable side effect of stretching a framework for a film onto a video game. If Lara could somehow escape death without a scratch, then this dissonance would likely disappear, but so would the mechanical challenge that is associated with games. The accepted tradeoff, then, is seeing Lara die a dozen brutal deaths over the course of the game. It’s a discomfiting display of torture porn.9

Altogether, these factors ultimately produce a strange, dissonant sensation as Lara’s status oscillates between being the hero of our story and an object of voyeuristic brutality.

Other elements of the slasher film present themselves in small ways throughout the game to less dissonant effect. Clover writes that “a phenomenally popular moment in post-1974 slashers is the scene in which the victim locks herself in (a house, room, closet, car) and waits with pounding heart as the killer slashes, hacks, or drills his way in.” In this vein, Lara is often pressed into tight tunnels or other crawlspace-like areas, enemies in frame, searching directly for her. Clover also notes that that “decidedly ‘intrauterine’ in quality is the Terrible Place, dark and often damp, in which the killer lives or lurks and whence he stages his most terrifying attacks,” and so of course, at one point Lara drops into a literal river of blood, wading through it to make her escape:

The ineptitude of classical authority figures is also a genre staple that appears prominently in Tomb Raider. Policemen, sheriffs, and civilian groups (think the lynch mobs of the Halloween franchise) are all unhelpful and incompetent. Lara gets a distress signal out after a dizzying climb to the top of a radio tower, making contact with a rescue crew. The first helicopter pilot to arrive crashes immediately afterward, struck down by the island’s tempestuous storms. The second fails to heed Lara’s warnings about the island’s curse and also fails to extract the survivors from the island, crashing once again and dying in the process.

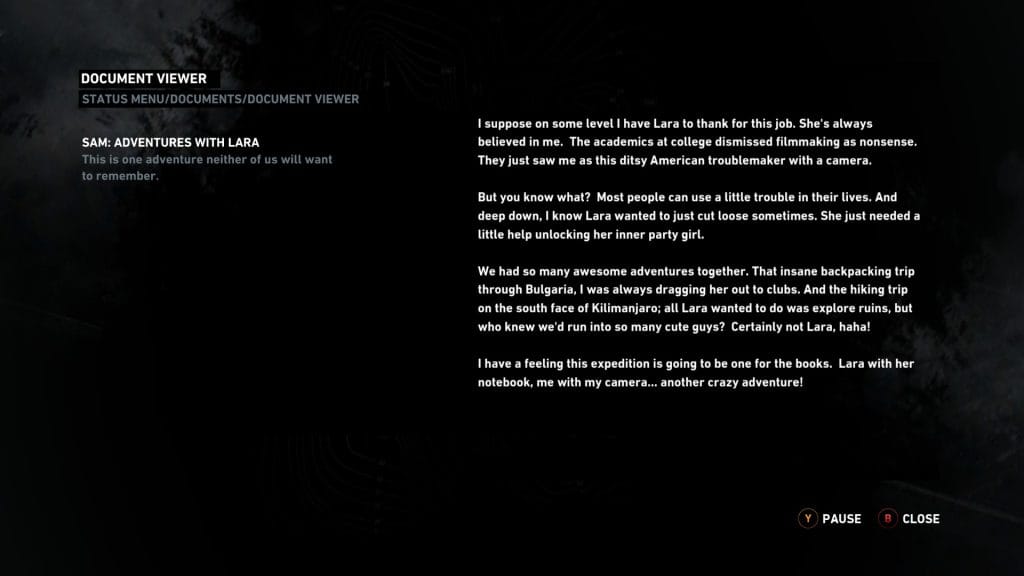

Another key element of the slasher film is the presentation of victims as sexual transgressors.10 Even the sexual dichotomy between the Final Girl (often presented as virginal) and the Victims (as sexual transgressors) is present, albeit loosely. Roth and Grim have little to add to this area, but Whitman is going through marital troubles, and Alex is openly attracted to Lara, though this is at least framed charitably as being not just physical but also rooted in an admiration for her courageous nature. Sam’s audio logs also characterize her as the party girl of the two between herself and Lara, and Lara neatly follows stereotypical Final Girl tropes by being a nerdy bookworm who shows no interest in the opposite sex.11

Despite these numerous similarities, those familiar with the game likely see one key element that stands out as notably dissimilar: the Killer. While the Sun Queen Himiko is the ultimate antagonist of this story, the degree to which Himiko’s machinations influence the plot is largely withheld until the final act. It would be more accurate to say that for most of the game, it is the island of Yamatai itself that is the “Killer.” One could argue that Mathias, the leader of the Solarii cult, fulfills the role of the Killer, but in truth, he does little to harass Lara herself until the very end of the game.12

Supernaturally violent and powerful thunderstorms both cause the Endurance’s initial crash and sabotage the crew’s later escape attempts. Vicious wolves attack Lara, another natural extension of the island’s hostile nature. Even the members of the Solarii cult, native to Yamatai, are characterized by their generic-ness. They present as subunits of “the island” instead of as discrete, individual entities.13

Overall, the game produces a thematic, slasher-esque experience, a tension that is really unique to the first entry of this trilogy. But the lack of a singular “Killer” entity has downstream effects on the execution of Lara Croft as the Final Girl, which hampers the effectiveness of Tomb Raider’s narrative as a whole.

Lara as the Final Girl, and the Failings Thereof

Lara does not exemplify every trait of a Final Girl, at least as defined by Clover, but she embodies many of them. One of the qualities of the Final Girl is her justified use of violence to fight back; one of Lara’s most notable qualities is that she commits acts of violence in absurd quantities, at least relative to other Final Girls. Isabel Christian Pinedo, in her book Recreational Terror: Women and the Pleasures of Horror Film Viewing, describes the moral imperative of the Final Girl as follows:

The slasher film violates the taboo against women wielding violence to protect themselves by staging a scene in which she is forced to choose between killing and dying… Having chosen to live, she is forced to use extreme violence not once but repeatedly against a killer who will not stay dead. Each time he rises from the ground, she must renew her attack. But her violence is justified, framed as a form of righteous slaughter.

It is in this area that Tomb Raider strays from the slasher-film framework, which causes fraying narrative problems. Because the Killer in Tomb Raider is not an individual for most of the game but rather a collective threat posed by the island, how Lara fights back against the Killer becomes more complicated.

In Tomb Raider, the Killer is composed of discrete subunits: the individual Solarii cultists that serve as enemy fodder for much of the game. Lara’s efforts to fight back against the island cannot be measured in small maimings but rather in individual murders. It is one thing to stab the axe-murderer who is chasing you down, and quite another to contemplate the murder of dozens, especially when the work itself frames the act of taking a life, no matter its justification, as guilt-inducing.

Early in the game, Lara is infamously captured by a male cultist who intends to sexually assault her, grabbing her by the neck and forcefully positioning her against a barricade (a somewhat infamous moment when it was revealed in trailers and previews, as the developers were fairly cagey about calling this rape or sexual assault in interviews). After a struggle, she wrests a pistol from her assailant and kills him, shooting him in the head. She cries and retches in horror after. Terror is one thing; guilt is another, and a significant departure from the slasher mold.

Let us contrast with a famous example: Laurie Strode’s final battle with Michael Myers in Halloween (1978). Laurie Strode (Jamie Lee Curtis) physically harms Michael Myers several times in the chase that begins once it is clear she is the Final Girl. Indeed, it is her choosing to actively fight back that marks her in the audience’s eyes as the worthwhile horse to back in the race, the character worthy of the audience’s support. While the act of committing physical violence is no doubt traumatizing on some level to Laurie, she is in such a state of heightened distress that it’s fair to conclude that guilt hardly plays a role in her psychological state.

In roughly the time that elapses between Laurie stabbing Michael Myers in the neck with a needle and the end of the film, Lara shoots the man who sexually assaults her in the face, catastrophizes, internalizes, kills six more men, and then has the following conversation with Roth. It spans five minutes of playtime.14

The video game nature of Tomb Raider — a dozen-hour adventure with repetitive combat sequences — is contrasted with the intense, often just minutes-long final confrontation scenes in slasher films proper. The justified violence — the righteous slaughter — that the Final Girl enacts upon the Killer typically happens in a frenzied burst of action, what might be 10 minutes of hectic scrambling and running and fighting. Is it abnormal? Yes, but it is justified.

In contrast, Tomb Raider is not a two-hour film but a 12-hour game; Lara’s “justified violence” is not merely two stab wounds on the body of the Killer, but the murder of hundreds of cultists accumulated over the course of hours and days. Such is the outcome when the core gameplay unit of your game is 3rd-person cover-shooter set pieces. When a video game protagonist picks up a gun, the expectation is that you get to empty full clips into waves of enemies, and that is exactly what Lara does, with great aplomb.

One area in which Tomb Raider was maligned: Though its story was well-written, the game quickly whiplashed from Lara’s horror at her first kill to the ludonarrative dissonance of her following in-game actions. The crux of the issue here is that because Tomb Raider is so long, because its mechanical currency is combat measured in kills, because the Killer is not a single entity but an entire cult’s worth of people, the “moral alibi” granted by the framing of Lara as the Final Girl, of her justified and righteous violence, runs out fairly quickly.15 Lara shifts from the frenetic, desperate frenzy typically applied to Final Girls and instead evolves into rage and resolute determination. Instead of the hunted, she becomes the hunter.

Lara as the Killer, or the Perils of Being a Ludonarrative Dissonance Industry Baby

I want to take a slight detour to discuss a select few industry trends during Tomb Raider’s development, which I think will elucidate both why Crystal Dynamics moved Lara’s character in this direction and how this invited the kinds of criticism Tomb Raider received.

Released in 2003, Tomb Raider: The Angel of Darkness was a critical and commercial failure. In the game’s aftermath, publisher Eidos Interactive handed over the reins of the series from Core Design to Crystal Dynamics, who remain the stewards of the franchise to this day. Tomb Raider: Legend, released in 2006, kicked off the “LAU trilogy” era of Lara Croft and marked a return to form for the series. Tomb Raider: Anniversary and Underworld released in subsequent years to respectable reviews but middling commercial success.

Meanwhile, Naughty Dog’s Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune released in 2007 to great reviews, higher than any Tomb Raider game had received since the original. The game draws much inspiration from the original Tomb Raider games and the Indiana Jones film franchise, but with some differences. Naughty Dog’s co-president at the time, Evan Wells, even noted some specifics (via GameSpot):

From a character standpoint, Nathan Drake is an everyman who struggles to get by, who you can see on his face that he’s stressed out as he’s flinching from bullets ricocheting off the cover he’s hiding behind, while Lara is the more stone-faced acrobat, perfect landing every time. And then the gameplay, obviously we were very focused on third-person cover-based play, while theirs is more auto-aiming and a little more heavy on the puzzle-solving.

In 2009, Naughty Dog’s follow-up, Uncharted 2: Among Thieves, released to critical acclaim and cemented itself on countless “best games of all time” lists. Two years later, Uncharted 3: Drake’s Deception dropped to slightly lesser, but still stellar, reviews. Uncharted hits similar notes to Tomb Raider (to the point that it earns the moniker “Dude Raider”), but is much more cinematic and polished. Especially with Uncharted 2 and 3 releasing in the post-Underworld gap, at the time it felt like Uncharted had gone out and eaten Tomb Raider’s lunch. (To be fair, lead developer Crystal Dynamics was undergoing a corporate takeover courtesy of Square Enix at this time.)

Simultaneously, genre media as a whole had taken a turn for the darker, starting in the mid-2000s. The Bourne franchise, Christopher Nolan’s Batman trilogy, the advent of FromSoftware’s Dark Souls series, Daniel Craig’s James Bond, and so on are all examples of this trend. With all of this in mind, it’s easy to see why Crystal Dynamics felt a major shakeup was necessary. Sales of the series were flagging, and Uncharted had filled the pulpy treasure-hunter action-adventure niche that Tomb Raider once occupied. Everything else was going darker and grittier, so why not them? Why not take Tomb Raider in a different direction?

2007 was also the year Clint Hocking published a blog post critiquing Bioshock (2007), which is where the term “ludonarrative dissonance” was coined. The concept fueled discourse (at least among the highbrow-minded) for some time; Naughty Dog in particular dueled with the concept often, ranging from Neil Druckmann denying that it was a relevant factor in Uncharted 4’s development to becoming (intentionally or not) a central tension in The Last of Us. In 2012, one year prior to the release of Tomb Raider, 2K Games released Spec Ops: The Line, which ended up serving as the game that most directly interfaces with the specific militaristic bent of the ludonarrative dissonance of its era. All of this contributes directly to the motivations Crystal Dynamics had for rebooting Tomb Raider, and also to the criticisms it received at the time.

It might have been possible to paper over the criticisms of ludonarrative dissonance if Tomb Raider handled some details differently. As mentioned, Nathan Drake also receives similar criticisms, but not quite as harshly. A large part of this is because Naughty Dog adjusted to these complaints accordingly, especially after the second entry. Outside of one strange dialogue exchange with Zoran Lazarević, the villain of Uncharted 2, the narrative does as much as it can to avoid drawing attention to the cost in life of Nathan’s actions. Even when Nathan does kill, he does it like he’s embarrassed to do so, a quick jerk of his arms as he cracks a guard’s neck. Often, his “kills” aren’t even kills, clearly knocking enemies out (we’re not going to examine the deleterious effects of getting hit so hard you go immediately unconscious). Enemies rarely, if ever, comment on his actions.

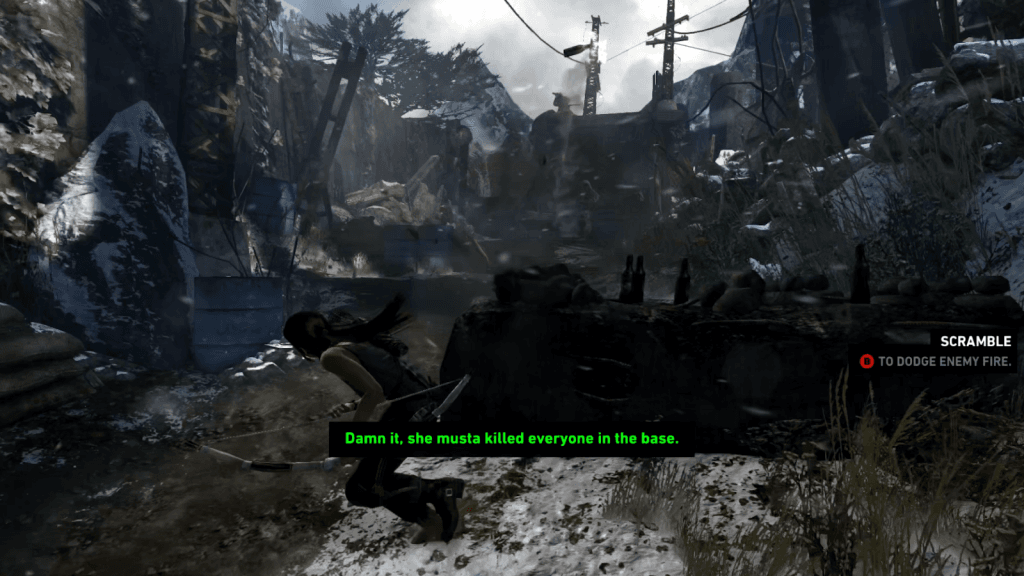

Lara, on the other hand, is not nearly so subtle. Every one of her stealth kill animations very clearly and very obviously results in a dead body. Fire arrows set enemies on fire, and they scream in panic and horror. Lara’s animations are brutal; she screams in rage when she swings her axe in a way that I can never remember Drake doing. Some of the things she does are visceral:

There’s an encounter with a wounded cultist, perhaps 20 minutes after her conversation on the ladder with Roth. The cultist, in pain and on the verge of a slow death, asks for an act of mercy. Lara’s response is cold and immediate: “Go to hell,” she says, unloading into his face.

Moreover, the cultists start the game viewing Lara dismissively, as a nuisance, and slowly transition their attitudes through the course of the game.

As her kill count goes up, the ambient dialogue becomes more frantic. The Survivor trilogy as a whole highlights how destructive and murderous Lara is, with cultists bemoaning how she has murdered so many of their allies, emphasizing the impact of her violence.

By the end of the game, she has turned the tables on the Killer: She is the one to be feared. The following clip is near the end of the game and is one of her more famous lines, actively stating her intention to kill as many men as she can:

Lara’s animations, her dialogue, and the way her enemies react to her all culminate in this effect that positions Lara in a space that feels almost as morally transgressive as her enemies. Lead writer Rhianna Pratchett has said in an interview that the “I’m not that kind of Croft” scene was one of the scenes that the whole game was built around. The intended effect was, I presume, to emphasize Lara’s lack of self-confidence to begin this story versus the more confident version of her that exists at the end. In practice, it reads more like her acknowledgement that the difference between her and her father is that she is willing to commit great acts of violence to get what she wants (I am fairly certain Richard Croft’s body count was a fraction of Lara’s, if not zero):

Largely, the inconsistency with which the game treats Lara’s violence is a problem. The developers could have done what Uncharted or the Indiana Jones movies do, which is to downplay it (and its real-life moral repercussions) as much as possible. It would still be a point of contention, but at least it wouldn’t stick out like a sore thumb. Instead, the game sometimes treats Lara’s violence as “real,” as something traumatizing, transgressive, and transformational; at other times her actions are treated as casual and heroic.

Several hours ago, Lara was mourning a dead deer! Her allies don’t just brush Lara’s actions off as something of little consequence, as if seeing the college student tagging along on their expedition set three human beings on fire without a moment of remorse is normal. They celebrate it with zero hesitation.

The way in which the Survivor trilogy moralizes Lara’s violence will continue to be an interesting point of discussion, specifically in Shadow of the Tomb Raider. I find it to be one of the most fascinating elements of her character, and one of many notable departures from her Legends timeline counterpart. But even without comparison to her other chronologies, the degree to which these ludonarrative dissonances are discussed — as a primary criticism of the trilogy — shows how central it is to the overall reception and legacy of this version of Lara.

Finally, I do want to note one possible view of Lara’s actions in this game: Because they occur as a result of being in an extraordinary state of heightened duress, they don’t actually reflect her true self; it is all an adrenaline and stress-induced haze that dissipates upon crossing the threshold back to society. The final scene puts those notions to rest:

Here, we see Lara standing to the side, noticeably separated from the rest of her comrades. While Reyes happily talks about her daughter and Jonah reminisces about mango smoothies — the things they can do once they have crossed the threshold and returned to their home — Lara remains isolated. The sailor who comes up to her rightly recognizes that something about her has changed irrevocably, his metatextual understanding of the hero’s journey kicking into gear.

If there were any doubts left after this, Lara herself dashes them, stating it as plainly as can be. “I’m not going home,” she says, as the game’s tagline appears backlit by a blinding white that fades into the title. The message is clear: This is the creation of Lara Croft, the Tomb Raider. This is the new normal, what she will be from this point on. For the others, this was a traumatic experience, but not one that has transformed them. For Lara, this experience has revealed to her who she really is, and given her a new purpose.17

All Roads Lead to Unification

It’s not clear that Crystal Dynamics always intended for the Survivor trilogy to lead into the Legend chronology — at the very least, there are minor canonicity conflicts that make it seem like this was not the intended path (largely regarding Amelia Croft, Lara’s mother, but it’s the level of continuity error that can easily be smoothed over with a slight retcon). As explored, there’s a lot to unpack with the Survivor trilogy — we haven’t even gotten to the canonical side content explored in the comics and novels, much less Rise and Shadow. Choosing to fold all of that in is a bold move, and I’m very curious to see whether Crystal Dynamics will choose to take this head-on or try to play down as much of it as possible, using the unification more as a tool to appease both sides of the fanbase than as a real narrative exploration.

Despite all of this, more than a decade removed from Tomb Raider (2013), I’m hard-pressed to categorize the reboot trilogy as anything less than a success. Tomb Raider sold 14.5 million units, more than any other entry in the series, re-established the series as a bona fide AAA franchise, justified two full-fledged sequel entries, a Hollywood film, and two seasons of a Netflix animated series. While Lara’s journey in the reboot inevitably carries some baggage, the overall package was clearly appealing enough — narratively and mechanically — to revive the series and, frankly, take it past its former glory days to even new heights.

On a personal level, while I love both versions of Lara, I do find the Survivor version to be particularly fascinating. The Lara we are introduced to in Tomb Raider is battered, beaten, and endures inhuman levels of punishment; she’s also a brave, caring, and endearing character who overcomes incredible obstacles through sheer determination and willpower.

The ascension of the series and Lara herself will only continue with the sequel, Rise of the Tomb Raider, which I’ll be covering in the next part of this series (with a quick detour into the realm of the comics, which features some truly fascinating characterization). Hope you’ll join me for Part II!

Footnotes

- The Survivor trilogy spawned three mainline games, two comic book lines, a Hollywood film, and two seasons of an animated Netflix series. Tomb Raider (2013) remains the highest-selling individual game in the franchise to this day, and threw Lara back into the mainstream gaming spotlight after the relatively underwhelming success of Underworld. ↩︎

- I don’t go too deep on Sam/Lara here, but I will in my next piece, which will cover the comics in detail.

↩︎ - It’s rare to see two distinct versions of a character coexist. Generally, it’s reserved only for the most popular superhero characters, where you can see different multiversal iterations of characters like Batman showing up simultaneously, for example.

↩︎ - I stress again that my description here is how she is introduced; what she ends up becoming is something else entirely. Also, to be fair, she isn’t a wallflower; she has a perfectly reasonable amount of self-confidence for a woman in her early 20s. She’s willing to stand up for herself, as we see in the flashbacks we are shown through Sam’s filmed footage.

↩︎ - I do acknowledge that Lara in season two of The Legend of Lara Croft is much closer to her classic portrayal. However, I think that the show also sort of glosses over some events of the trilogy and is more of a forced evolution of the character than a truly earned character arc. I’m still a fan of it overall, though, and I will cover it in future parts of this series.

↩︎ - I’ll be discussing ludonarrative dissonance in more detail later, but to provide a general definition: Ludonarrative dissonance is the conflict between the narrative told through a video game’s non-interactive elements and the narrative told through its gameplay.

↩︎ - “The death of a male is nearly always swift; even if the victim grasps what is happening to him, he has no time to react or register terror… The murders of women, on the other hand, are filmed at closer range, in more graphic detail, and at greater length.” (Clover, 35)

↩︎ - To be clear, there is a significant degree of violence on screen directed at women. In addition to Lara, Sam is also subjected to trauma, getting kidnapped by the cult midway through the game, and her distress at this is notable. So notable, in fact, that it forms the backbone of many of the plot arcs in the comics.

↩︎ - With all this being said, it is worth noting that every “canonical” character death in this game is a male: The unnamed crewmen of the Endurance, every member of the Solarii cult that Lara slaughters, Roth, Grim, Alex, and Mathias.

↩︎ - “In the slasher film, sexual transgressors of both sexes are scheduled for early destruction… Killing those who seek or engage in unauthorized sex amounts to a generic imperative of the slasher film. It is an imperative that crosses gender lines, affecting males as well as females.” (Clover, 34)

↩︎ - There’s also quite a bit of literature that examines the Final Girl as being a masculine-coded entity or as a lesbian. I mention this because Sam and Lara’s relationship is notable; it clearly struck a chord in the fandom, wherein it’s Lara’s most popular relationship pairing by a country mile (check out the Tomb Raider AO3 tag if you want to verify. Also, full disclosure, I’m one of those people).

Indeed, much of Lara’s motivation to keep going, outside of general survival instinct, revolves around saving her “friend” Sam. In the trilogy proper, Sam has a sort of “ghost who haunts the narrative” presence, having been almost entirely written out of two sequels, but she plays a large role in Lara’s canonical characterization that follows in comics. We’ll get into that in the next part of this series, where I’ll examine the comics and other canonical side-projects in more detail. Don’t worry, I’m not trying to gloss over this aspect of her character!

↩︎ - Another common element of the Killer is that they are in some way psychosexually impacted if male, or they have been betrayed by a man if female. This doesn’t really apply to Tomb Raider: Himiko’s state of decaying undeath is actually caused by a betrayal from one of her female shrine maidens, whose motivation is not sexual in nature at all. Mathias, who is trapped on the island by a matriarchal figure (Himiko), potentially represents a form of oedipal cathexis, which is not an uncommon trope in the genre (think Psycho) — but even for me that’s kind of pushing it. Sometimes the curtains are just blue.

↩︎ - With the exception of Mathias, I can recall exactly two names Solarii members: Vladimir (who I recall is named in the credits but not elsewhere) and a guard named Dimitri, who is killed by Lara literally within seconds of his name-drop.

↩︎ - To be fair, lead writer Rhianna Pratchett has publicly spoken about how the pacing here was a major misstep in an interview with Eurogamer. These numbers aren’t an exaggeration: I scrubbed through my playback recordings to verify.

↩︎ - Of course, that Lara needs a moral alibi at all is perhaps something that should be questioned. The gendered double standard here is the topic of the essay The Popular Pleasures of Female Revenge (or Rage Bursting in a Blaze of Gunfire) by Kirsten Marthe Lentz, which is a fun read if you want to dive into this.

↩︎ - Despite the fun visual parallel here between the two franchises, the more apt comparison is probably to Daniel Craig’s James Bond. Similar to Lara, Bond was a campier action-adventure series that underwent an edgy makeover. There are notable similarities: lines like “I hate tombs” and “Do I look like a give a damn?” deliberately signpost a rejection of the characterization of prior entries, Yamatai and Vesper’s death both serve as especially traumatizing events that scar our protagonists permanently, and both fall back on violence when cornered (and are quite good at it, too).

↩︎ - …Kind of. I’m overselling a bit here, but only in the sense that some of the canon commits very hard to the idea of Yamatai as a soul-baring, foundational experience that reveals Lara’s inner brutal nature (the comics, Shadow of the Tomb Raider, and the tie-in novel Path of the Apocalypse), while other parts of the canon do not (Rise of the Tomb Raider and The Legend of Lara Croft). The comics, in particular, are obsessed with the idea of Lara’s killer instinct, which we’ll cover in my next piece.

↩︎

Huge video game, comic book, and anime fan. Spends way too much time watching things he doesn’t like. Hates Zack Snyder. Mains Falco.

![Tomb Raider - All Death Scenes [HD] Compilation](https://i.ytimg.com/vi/iyVHV7ct4gU/hqdefault.jpg)