Warning: Full spoilers for LIVE A LIVE

While the role-playing game genre features many titles that I adore for how they break convention and demonstrate a thorough, consistent sense of identity, LIVE A LIVE sticks out as a notable counterexample. A 1994 RPG developed by Square and directed by Chrono Trigger co-director Takashi Tokita, the game presents players with seven chapters which can be played in any order, each with a different setting, time period, and cast of characters.

For example, one chapter follows a prehistoric caveman named Pogo trying to save a cavewoman from a T. rex, while another follows a spherical robot named Cube trying to save the crew of a besieged space vessel in the “Distant Future.” Other chapters take place in Imperial China, Edo Japan, the Wild West, the “Present Day,” and the “Near Future.” Each bears a unique aesthetic, soundtrack, and distinct gameplay style. Cube’s chapter in the Distant Future is notable for being largely devoid of combat.

While the concept is distinctive, in practice it makes liberal use of archetype and cliché in each chapter. It’s also easy to determine what it’s drawing inspiration from. Anyone with basic knowledge of classic films will plainly see the influence of The Magnificent Seven, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Alien, just to name a few. And the unlockable eighth chapter, with its damsel in distress plot and silent hero, is clearly looking to establish its world as a rather thin replica of the average Japanese fantasy RPG.

In fairness, none of this necessarily entails poor quality. I certainly enjoyed the stories for what they were. But for the average first-time player, it isn’t immediately obvious what the game is trying to communicate with its constant shifts in genre and time period. By the time I had finished the seventh chapter, nothing had truly cemented this game as a classic. There would have to be something truly outstanding about the finale to tie all its disparate parts together.

Thankfully, I found that it easily lived up to that standard. LIVE A LIVE’s finale not only stuck the landing but provided a synthesis of each individual chapter’s themes that elevated them beyond the sum of their parts. And the way it did so bucked convention not just with twists and subversion, but with how its final hours recontextualized the simpler early chapters.

LIVE A LIVE’s finale not only stuck the landing but provided a synthesis of each individual chapter’s themes that elevated them beyond the sum of their parts.

How the Stage Is Set

The changes of the 2022 remake may count for a lot here, with gorgeous pixel art, a stunning remixed soundtrack from original composer Yoko Shimomura, and stellar voice acting. And yet, despite all the flourishes of its presentation, I believe the story of LIVE A LIVE remains one of its strongest elements. In fact, I think it’s some of the most effectively lean storytelling that the medium has to offer, letting its early story beats bask in a deceptive minimalism that, come the final chapter, gives way to a strong thematic statement.

The key turning point is the game’s eighth chapter, the Middle Ages, unlocked after completing the first seven. It is the story of Oersted, a celebrated knight who seeks to rescue his fiancee Princess Alethea from the clutches of the Lord of Dark. For two thirds of the chapter, it plays out like the most cookie-cutter JRPG possible. It’s the only chapter up to this point to have traditional random encounters instead of avoidable enemies, and Oersted, like many protagonists of the genre, does not talk.

Unfortunately, his quest takes a horrific turn in its climax. An illusory figure tricks Oersted into killing Alethea’s father, the King, and the hero is declared an enemy of the kingdom. Oersted ventures to the Lord of Dark’s fortress and finds his best friend Streighbough in its innermost sanctum, revealing himself as the one undermining Oersted’s reputation out of jealousy for his engagement. The two duel to the death, with Oersted emerging the victor, but when Alethea finally emerges, she rejects him, having fallen in love with Streighbough, and takes her own life. With everyone who could have believed in him dead and the rest of the world calling for his death, Oersted can do nothing but despair.

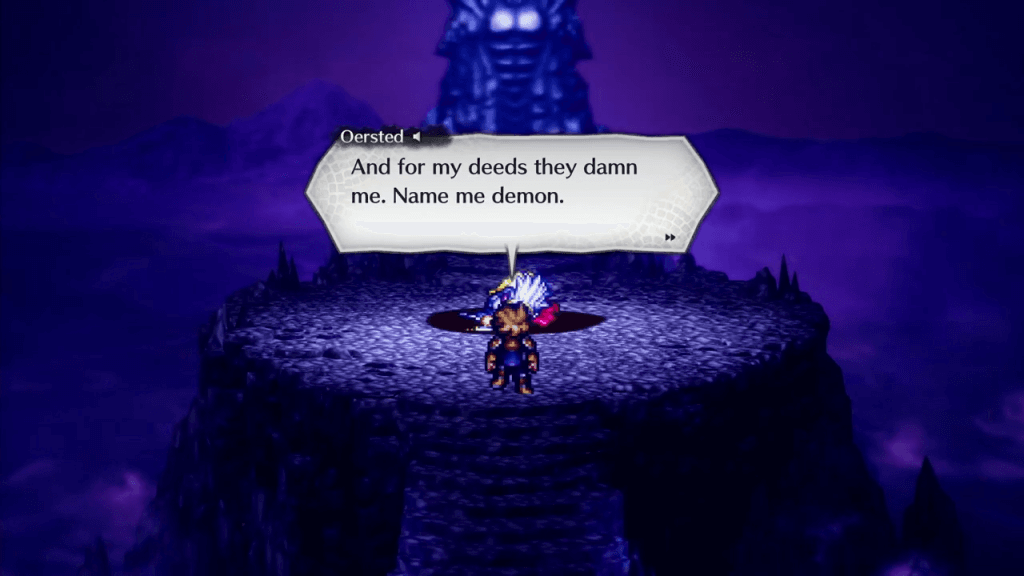

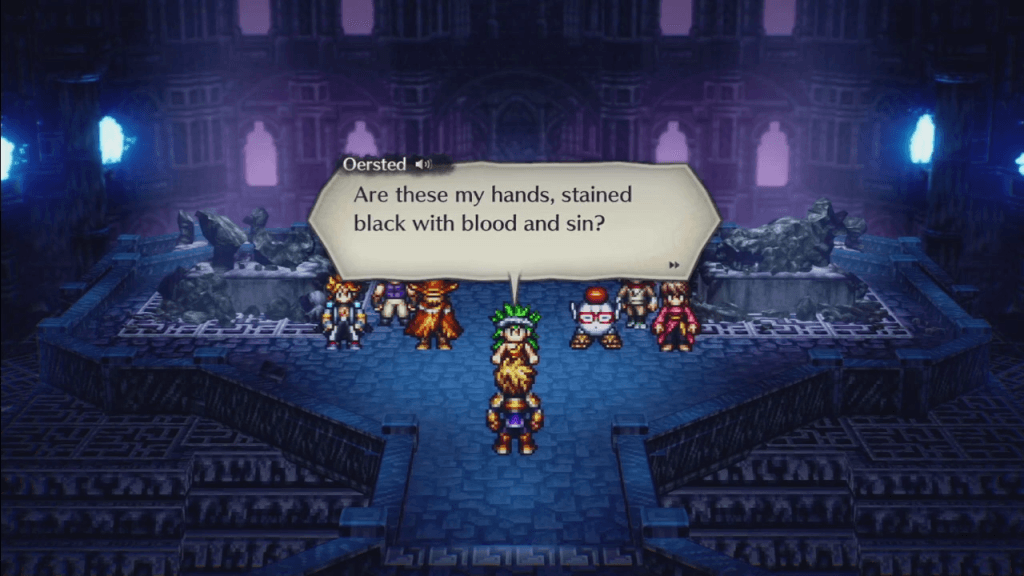

But it’s how he does so that makes this scene so fascinating. When his emotions finally boil over, Oersted, for the first time in the chapter, speaks aloud. He laments his fate, his being left alone with his name forever tarnished. His sadness soon gives way to rage, saying that he did all that people asked of him and received nothing for it. In return, he takes the jeers of the people to heart and takes on a new title: The Lord of Dark, Odio. The name that all the prior chapters’ villains have in some way borne.

The Perfect Rug Pull

This is one of the most memorable scenes in the game, if not the most, owed to clever foreshadowing and the strong genre subversion at play. The impact of Oersted speaking at this particular point is predicated on the understanding that his silence evokes the image of a traditional silent RPG hero, a la Dragon Quest. His shedding of a common heroic cliché communicates that Oersted is definitively not the hero anymore.

However, what makes this more than a neat detail is that Oersted does not see things that way. While the menu for the final chapter allows the player to select any of the prior heroes as the central fixture of their party, Oersted, or rather, Odio, is also present on the menu, and selecting him begins an entirely different version of the final chapter. By offering the option at all, the game isn’t just giving you a chance to play as the villain; it is placing you in the shoes of a man still convinced he’s the hero.

The game isn’t just giving you a chance to play as the villain; it is placing you in the shoes of a man still convinced he’s the hero.

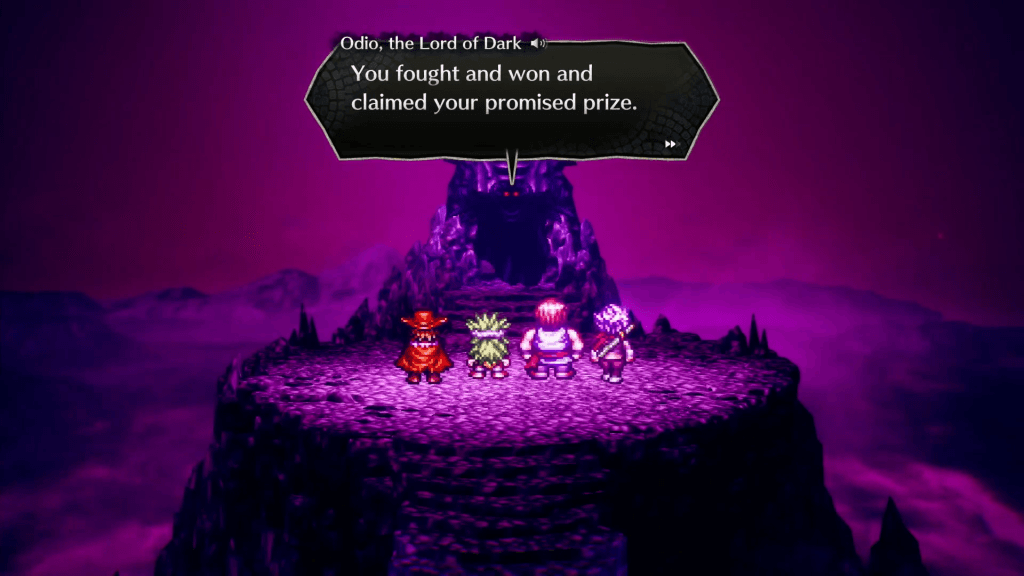

In this version of the final chapter, Odio gives each of the final bosses of the first seven chapters a chance to flip the script and win against the heroes who defeated them. He does so not because of a grand philosophy that unifies them, but because he now sees himself in them. Odio sees himself, and now these similarly scorned villains, as heroes. It is clear that LIVE A LIVE is not trying to genuinely argue for the moral character of, say, a T. rex trying to devour some poor cavemen or a rogue AI so dedicated to its mission that it turns on humanity. Rather, it uses Oersted to show how even the seemingly heroic can fall from grace, how people will justify doing terrible things or hurting other people, and how isolation can drive people to seek solace in unhealthy coping mechanisms. And Odio’s idea of coping goes far beyond his kindness to these unsympathetic villains.

If you choose a character other than Odio for the final chapter, he plucks the selected hero from their home and sends them to the Middle Ages, left to wander and group up with the other six heroes. But as you seek them out and prepare to fight Odio one last time, something about the kingdom feels wrong. Locations once full of people are empty, and random encounters with enemies now happen everywhere, even in the towns and buildings. There are beings capable of talking with the party, but none of them are human. Whether the realization sets in gradually or hits all at once when encountering the ghosts of the victims, it nonetheless hits hard: Odio has already killed every human in the kingdom. In fact, the ending of his version of the final chapter has him reduced to a shell of a man, begging for anyone to believe in him and wandering a kingdom now devoid of people.

This is a deceptively striking narrative choice. Plenty of stock, archetypical villains attempt to commit mass murder. But Odio is not merely some aspiring omnicidal tyrant; he has already succeeded in his ambitions. The first phase of the grotesque and bizarre final battle against him even takes place upon a pile of corpses. The sheer scale of his atrocities complicates how he should be dealt with and whether or not it’s justified to meet his violence with lethal justice even after the party has soundly defeated him. And despite everything he’s done, the way forward lies in forgiving him.

Recontextualizing the Mundane

LIVE A LIVE earns what would otherwise be a hackneyed resolution through its surprising consistency. Forgiveness and redemption are major common threads across almost all of the first seven chapters. Prehistory sees its hero, Pogo, allying with a rival warrior in the end, and the Near Future chapter resolves with its hero, Akira, forgiving his brother figure for secretly having killed his father. It makes sense that these people would act this way. Likewise, many of the protagonists are, like Oersted, outsiders. Whether they’re outlaws, exiled, or simply looked down upon by society, they know what a life without other people looks like. While there is no singular trait shared among all the heroes, there are no heroes who share nothing in common with one another.

The climax hinges on these commonalities, but what’s striking here is that these shared experiences are not at all obvious even when playing these chapters back-to-back. While LIVE A LIVE is clearly aware of the nuances of its story, it never flaunts or dwells on them until the very end. It is content to let its characters’ finer points sit in the background, and even when it finally acknowledges them, it is elegant, succinct, and to the point.

While LIVE A LIVE is clearly aware of the nuances of its story, it never flaunts or dwells on them until the very end.

While each of these aspects of the various heroes is present enough to make their later relevance in the finale feel earned, their relative lack of focus early on gives the climax greater emotional impact by showing the full relevance of each character’s circumstances come into full focus right at the dramatic high point. They may be cliché, but each of them could have chosen to respond to the hardship in their lives like Oersted did. In this regard, LIVE A LIVE’s use of cliché loops back around to brilliance in how it shows that even the most upstanding and straightforwardly good people are still people in all their imperfection.

Nowhere is this more apparent than right after Odio’s defeat. Depending on which character the player chooses to lead the battle against him, each has a different response to Oersted realizing how far he’s fallen, each relating to him through their own experiences. Lei, one of the disciples of Imperial China, empathizes, noting that as a thief, she also envied what others had and resented them for it. Masaru, the pugilist hero of the Present Day chapter, notes that even if he seeks strength, eventually it will fade to time and he will have to live with the choices he made. Akira forgoes empathy and instead admonishes Oersted for using his suffering as an excuse. Even Cube and Pogo, who cannot speak, offer Oersted comfort in his final moments, Cube in the form of flowers, and Pogo in the form of a hug. And despite all the hardship and hate Oersted has experienced, he is completely overwhelmed by the idea that a robot and a caveman who cannot understand his words empathize with his pain.

The Parting Words

These final responses to Oersted are perhaps the purest distillation of LIVE A LIVE’s most salient point: No matter what changes about people, there is always, in everyone, a capacity for great cruelty and great kindness. This is true both in the historical sense, that these characteristics will endure no matter the time or place, and in the personal sense. Oersted was a great hero who lost everything and turned his back on the people he once protected. As Odio, his most powerful attack invokes the image of his love, Alethea, degenerating from a saintly maiden to a horrific corpse. It is a summation of Oersted’s agony: the pain of falling from heaven into the depths of hell, now inflicted upon his enemies.

No matter what changes about people, there is always, in everyone, a capacity for great cruelty and great kindness.

But even having fallen so far, even having everything taken from him, and even having killed the people he had sworn to protect, Oersted is still capable of accepting and understanding kindness and love. And in his last moments, he strikes down the greatest manifestation of his own hatred himself, saving the other heroes and passing on in peace after imparting some ominous words tinged with an undercurrent of hope. Oersted dies saying that “In every heart the seed of dark abides,” but he knows firsthand that even if someone chooses to water that seed, hope still remains.

LIVE A LIVE, developed and published by Square Enix, is available on PC (via Steam), PlayStation 4 & 5, and Nintendo Switch.

Sean Cabot is a graduate of Framingham State University, where he also wrote articles for the student paper before writing for RPGFan. In addition to gradually whittling down his massive backlog, he enjoys reading comics, playing Magic the Gathering, watching as many movies as possible, and adding to his backlog faster than he can shrink it.