…Which May Well Might Be 15% of the Content in This Game

First things first: This isn’t a review of Baldur’s Gate 3. This is a review of my first playthrough of Baldur’s Gate 3, which spanned a mere 74 hours and 10 minutes of my life. (That’s in-game time; considering the time spent to lost progress and bugs, 80 hours is a better estimate).

Baldur’s Gate 3 is a game of such expansive caliber that it’s impossible for me to say that my single playthrough is enough to holistically ‘“review” the game, even after 80 hours. At the same time, how many people are true grinders, running through the campaign multiple times, racking up hundreds of hours to experience every branching story route and ending? Probably not many, which is why I feel that sharing my experience will at least be somewhat informative here. A full-throated retrospective of this game in its entirety after four playthroughs and 400 hours of exploring its every nook and cranny might read entirely differently—but for now, I present you with my thoughts.

Setting the Stage

I’ll get some objective details out of the way first to give you an idea of what parts of the game I covered in my first playthrough. My platform of choice was Windows, on a mid-end rig that was able to run the game with no performance issues at Ultra settings, save for one or two instances of NPC-dense areas causing minor stuttering and slowdown. (I am on Nvidia, however, and I’ve heard that AMD users are not faring so well in Act 3.) I played on Balanced difficulty (which was probably a mistake—we’ll come back to that later), with a custom origin character. I approached the game with a completionist mentality, so when I was prompted with clear progress gates (“Make sure you tie up all loose ends before you enter this next area”), I cross-referenced a list of available quests on the ever-unreliable Fextralife wiki to make sure I wasn’t missing significant amounts of content. I read all the dialogue, but I did mash space to make things move faster. I babied out on puzzles after 15 minutes.

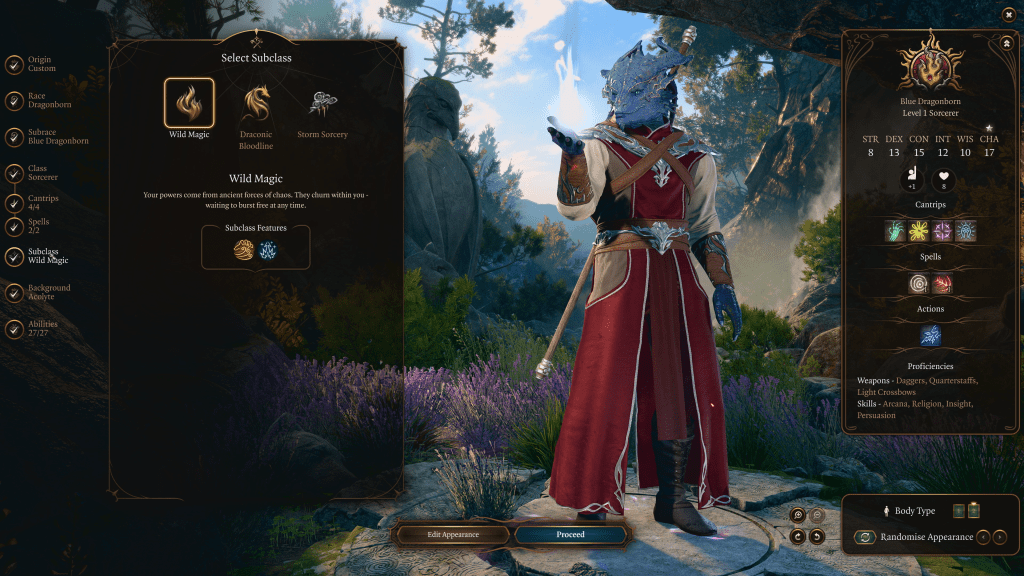

I played an Oath of Devotion Paladin, and leaned into those dialogue and narrative options as much as possible, meaning I chose hardline “good” options every time. (The game offers a significant amount of choice for players to indulge in otherwise, hence my “15% of the content in this game” caveat in the title.)

As an additional frame of reference: I’m an experienced tabletop player, currently playing in two Dungeon & Dragons 5E campaigns (the system upon which this game is based), with prior playtime in both editions of Pathfinder. I’ve also completed a good amount of CRPGs, having played both Divinity games, both Pillars of Eternity games, both Owlcat Studios Pathfinder games, and more, so my play experience was significantly influenced by that lens.

CONTENT, CONTENT, CONTENT

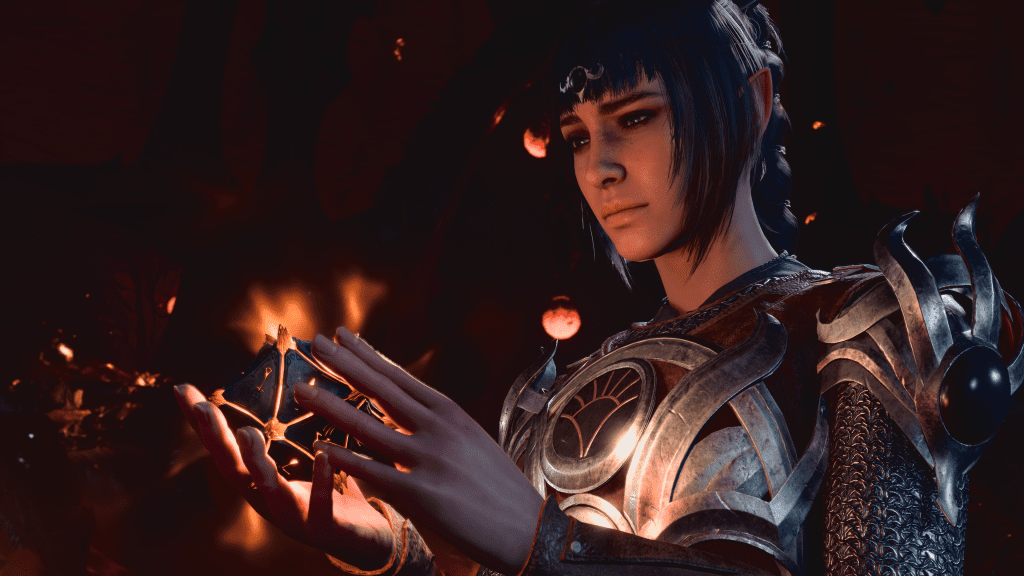

Right out the gate: Baldur’s Gate 3 is the highest-production “Western” RPG since 2015’s The Witcher 3. It is a truly deserving entry not just in the Baldur’s Gate series, but also in the lineage of expansive, narrative-driven, player-reactive RPGs that first put Bioware on the map—a gaming space that hasn’t quite been filled ever since the conclusions to Mass Effect and Dragon Age.

One of this game’s standout qualities is that it is just absolutely brimming with narrative content. This applies not only to the main plot or side quests, but to the dimensions in which you can interact with the world. In true tabletop fashion, the ability to cast speak with animals and speak with dead opens up new dimensions of dialogue and narrative interactivity. Yes, you can go talk to that critter and see if it saw what happened at the murder scene, and yes, you can just talk to the murder victim directly. (Both spells have been altered from their tabletop counterparts, essentially removing their resource cost to encourage players to cast these spells.) I noticed numerous occasions where a Druid’s Wild Shape feature—a tabletop staple—could open up an alternate avenue for approach, a distinct option outside of the typical roguish skullduggery, charming dialogue wheel interactions, or brute violence of most video games.

Baldur’s Gate 3 is comprised of three acts, and the primary main quest objective for each act can always be approached in multiple ways, something the quest log is upfront with you about. Many quests outright present themselves as having a two-pronged approach, and factions are presented in a similarly unambiguous fashion. Attack indiscriminately at first sight, ally with them, or even betray them down the line. Once or twice, this caused a strange bug where I triggered clearly incorrect dialogue that didn’t align with the decisions I had made—something I’m willing to chalk up to launch-month struggles.

The amount of direction the game provides might feel heavy-handed to some—this game is no Morrowind, what with its detailed quest log and persistent map markers—but that works in its favor, streamlining content and making sure the player always knows that they have somewhere to go to progress. It staves off that feeling of not knowing where to go or what to do, a feeling of indecision that plagues many games. And as I shared the story of my playthrough with others after finishing the game, I found out that there were many alternative paths and options I could have taken that didn’t openly present themselves to me, showing that I did in fact have much more freedom in my approach to problems than my quest log might have indicated.

A Grand Epic

Larian Studios made a big leap in story and writing quality between Divinity: Original Sin (an interesting world with occasionally charming dialogue) and its sequel (an engaging story with heartfelt characters and interactions, if laced with satire), so I was curious to see how that translated to working in an existing, licensed IP of grand scale. And I can confidently say that they truly exceeded my expectations in this regard.

Fans of the Baldur’s Gate series will find much to love in Larian’s iteration—perhaps more so than you might even expect. Given the decades-plus gap between the release of Baldur’s Gate II: Throne of Bhaal and Baldur’s Gate 3 (not to mention the century-plus gap in-game), I expected the connection with the series to be fairly loose. Instead, Baldur’s Gate 3 is quite rewarding for series stalwarts, featuring direct tie-ins to previous entries, with just the right amount of hand-holding for those who are unaware of the significance of certain characters.

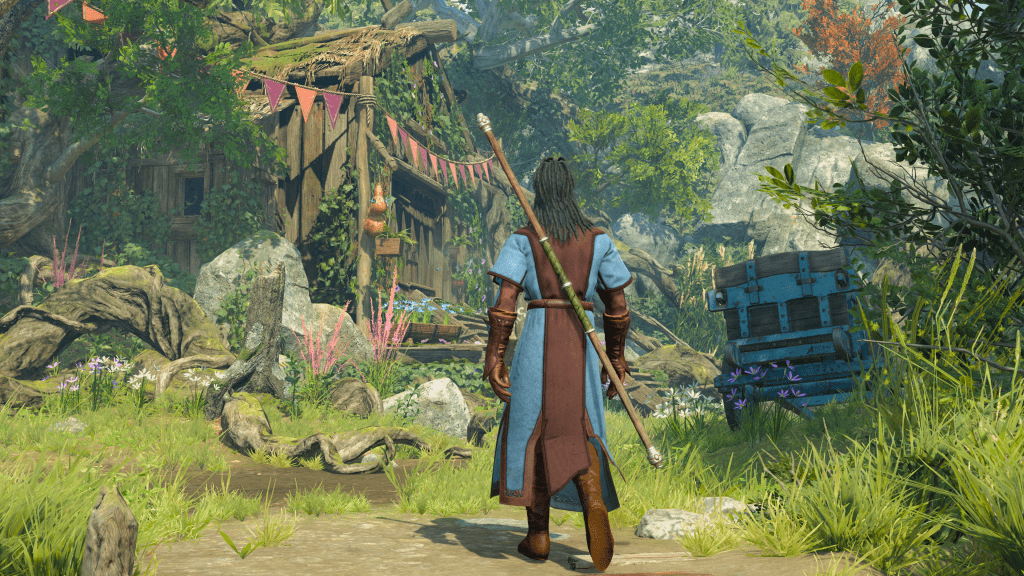

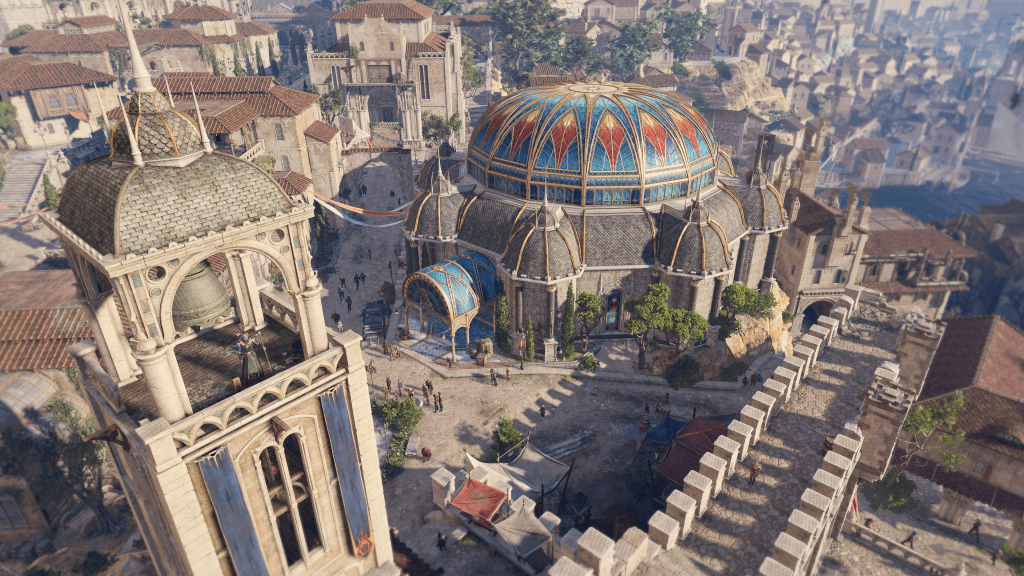

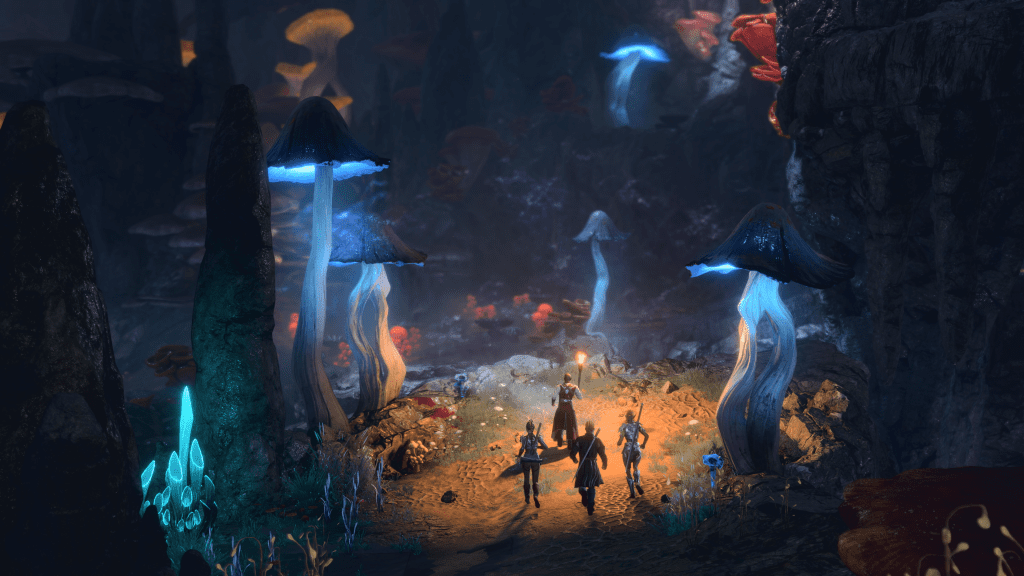

For those familiar with the setting of Faerûn through tabletop but not with the Baldur’s Gate series specifically, Larian has brought the world to life wonderfully, integrating factions players should be familiar with as well as numerous others. Iconic creatures dot the myriad encounters you will face, from your classic goblin archers to (potentially your very own, very cute) owlbears to mind flayers, dragons, and more. Faerûn has always served its purpose as a generic backdrop for fantasy campaigns reasonably well—though it has all of the shortcomings associated with that one-size-fits-all-approach (criticisms that are beyond the scope of this article)—and Larian has done a commendable job in presenting a lived-in, pseudo-verisimilitudinous version of the planes.

Notably, they have captured Faerûn’s most notable characteristic: its slightly absurd, menagerie-like quality, both in terms of locale, culture, race, and more. A smorgasbord of pulp tropes nailed onto a Tolkienesque foundation, Baldur’s Gate 3 manages to diverge enough from its medieval European fantasy roots by presenting numerous races, species, creatures, and planes to the player. The world of Baldur’s Gate 3 isn’t culturally rich, but it at least feels varied. There are enough wacky magical hijinks, shenanigans, and talking creatures that bring the chaos that is oft-associated with a game of D&D without veering into the occasionally satirical tone that Divinity took, and Larian’s commitment to playing things straight here pays off.

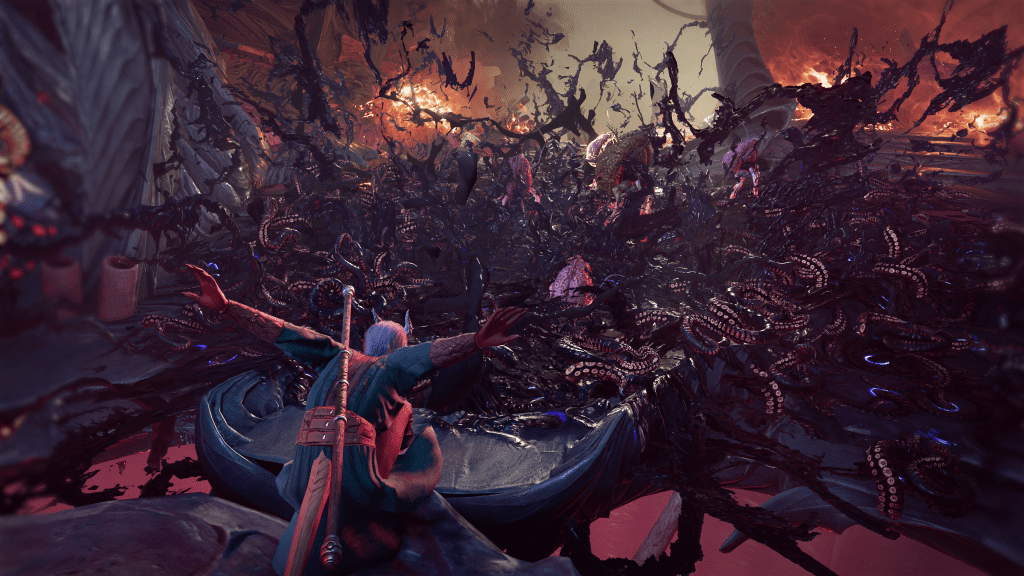

The meat of the story is also an engaging romp. It starts off strong by establishing a direct threat of constant presence: mind flayers are infecting folk in Faerûn en masse—including you and your party members—while creating and operating a growing cult to extend their power and accomplish their means. Eagle-eyed players who played the tabletop campaign Descent Into Avernus, a module released in 2019 that sets the table for the game, will notice key tie-ins as well, both in the early going as well as during some late-game revelations.

The mind flayer tadpole also serves a purpose as a useful metanarrative device: Infected can tug on each other’s psionic connection, providing a sort of mind-meld that works as a social lubrication, immediately marking NPCs of note and forcing the issue of your “special-ness” upfront, as well as providing mind-reading capabilities. The overarching story isn’t presented as much of a mystery, but the way you can deal with individual roadblocks often is, and it is in that veiled mirage of freedom of choice that the story shines. Disparate factions and scenarios all become interconnected by the spread of the mind flayer sickness and growing strength of their cult, tying everything fairly tightly to its main narrative.

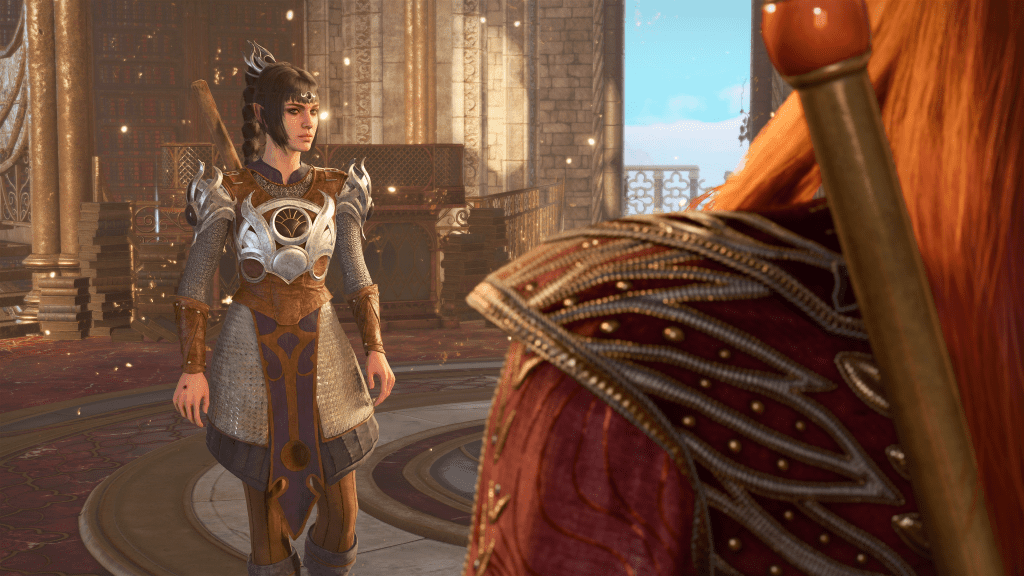

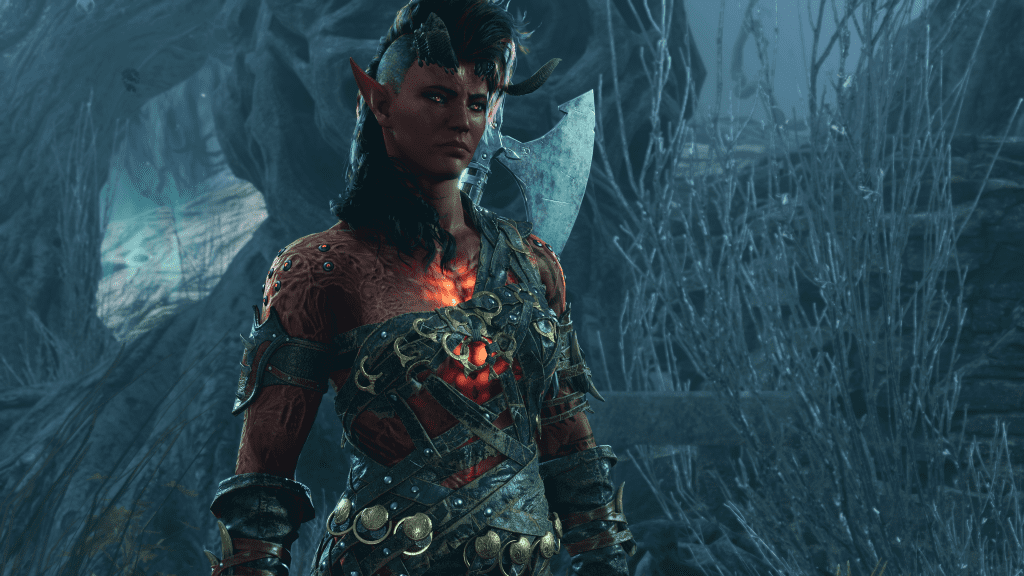

The companion characters are standout here as well. Larian has only improved over the years in this regard, and our crew of dysfunctional heroes is certainly their best work. Varied in race, morality, sexuality, and background, the cast of companions is charming, and I found myself rotating out party members constantly so I could engage with all of them as much as possible. A handful of companion questlines were a particular highlight of the game, showcasing the character’s growth over the course of the story, replete with gut-wrenching choices and heartrending moments. Sadly, not every companion’s questline was up to par, with some languishing for dozens of hours before cropping up right at the end, or in some cases, dropping off the map entirely.

The 5E-Sized Elephant in the Room, Part 1: Combat

Those with a keen eye might have picked up on the fact that I have been gushing about elements such as the narrative, writing, plot, and content extensively, but not things like character customization or the moment-to-moment feeling of combat. Frankly, that’s because I’m not as positive about them.

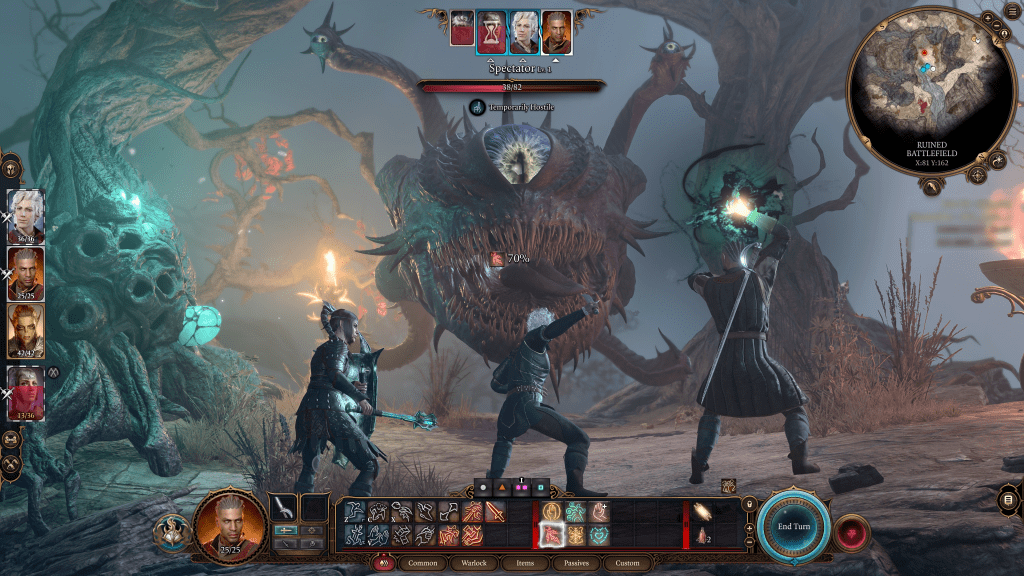

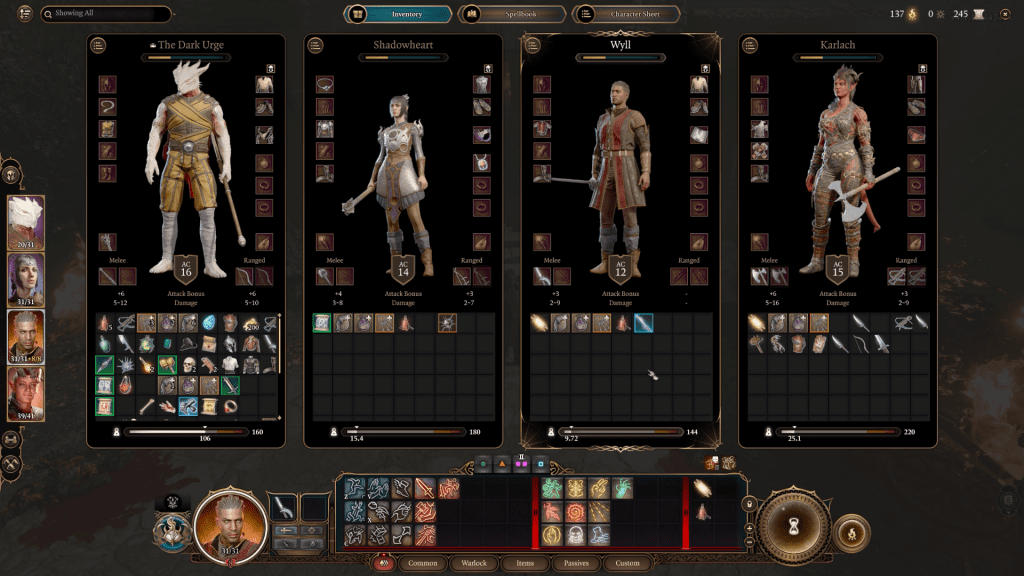

Firstly, for an RPG of this scale, character-building options feel quite limited. Nine of the 12 classes in this game only have three subclasses, with subclasses providing a limited number of unique features on top of the existing class chassis. Players with any amount of tabletop experience will find the number of options presented to players significantly shrunken down, with a smaller pool of feats, spells, and subclasses than what they’re accustomed to. Even with some crucial changes made from vanilla 5th Edition to Baldur’s Gate 3, I was very quickly able to hone in on a series of effective strategies, and I rarely found myself needing to adjust as I progressed through the game. Of course, there is merit to not overwhelming new players with inscrutable character-building options, but it feels a little too simplified for my taste.

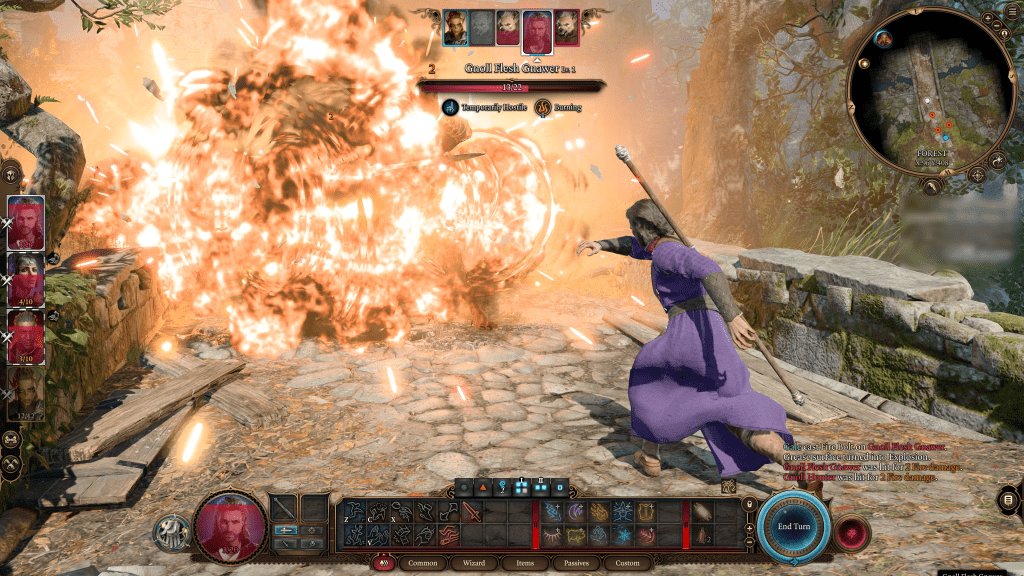

Many encounters do feel lovingly crafted, with unique enemies and a notable focus on terrain and heights. This turned out to be both a blessing and a curse, however, as consistent access to the Shove action on all characters made many fights a gimmicky pursuit of angling enemies off of cliffs or heights for instant kills, especially in the early levels, where the game is hardest. By the midgame, the difficulty curve had flattened considerably, and the journey from level five to 10 frankly felt like a breeze.

Larian introduced a number of overarching changes to the core gameplay of 5th Edition, and then added their own Divinity-esque twist by having a significantly expanded repertoire of conditions, terrain effects, and the like. I appreciated the breadth of additions here, but I ultimately ended up barely dabbling in them because the game was simply too easy, and straightforward tactics ended up doing the trick every time. (The game at launch has three difficulties: Explorer, Balanced, and Tactician. I played the game on Balanced; I’ve since started up a Tactician run, and thus far, my experience has barely changed.) As a result, statuses felt significantly more like “nice-to-have” bonuses instead of unique gameplay staples as they were in Divinity. There’s also a large number of statuses that encompass very similar effects: enwebbed, ensnared, entangled, and restrained are all very similar, for example, and it can feel like there’s a bit of information clutter, which isn’t helped by the game’s vague tooltips and lack of comprehensive in-game information compendium. Overall, I’m hoping that a future patch or an “Enhanced Edition” release will have more challenging difficulty options, which would certainly entice me more to revisit the game in the future.

Character pathfinding was also maddeningly inconsistent. Occasionally, characters would telegraph a certain path to a spot only to take a completely different route, ending up in a completely different location than the game had initially shown. This extended to out-of-combat scenarios as well, specifically in trap-laden areas. Unlike other CRPGs I’ve played, Baldur’s Gate 3 has no “auto-pause on trap detection” option (actually, no pause option at all), and I ended up needing to micromanage my party’s movement in minuscule chunks, lest my computer-controlled players walk right over a trap that had been detected moments prior. Moments like these added a frustrating veneer to much of the early game, and strongly made me wish that the game would snap to a grid once combat started (a mechanic that Solasta: Crown of the Magister pulled off with aplomb).

I also encountered some annoying moments where I tried to initiate an ambush or combat encounter of my own volition, and found that the game had not added all of my companions into the battle despite moving forward in some sort of asynchronous pseudo-real-time flow. Truthfully, it’s these moments—instances where I felt what I asked of the game was reasonable, yet somehow didn’t manage to execute properly—that most often caused me to reload. Even once I got the hang of things, I found myself needing to switch to a companion just to get them into the combat tracker, which was a compounding source of frustration.

One benefit of a three-dimensional virtual space compared to a two-dimensional tabletop is the ability to significantly incorporate heights and terrain into combat. Baldur’s Gate 3 certainly goes for this, but at times the game can’t keep up with its own creativity. The camera in particular struggled with encounters spanning large areas with multiple floors or height levels, and occasionally would pan or spin just as I was clicking to attack or move, resulting in frustrating mistakes. In one amusing instance, a barbarian in my party somehow jumped from inside the building onto the roof. That’s an extreme example, but I did run into movement issues and other minor glitches.

Elephant, Part 2: Resource Management as Gameplay

5th Edition D&D is a lot more focused on resource management than moment-to-moment tactics (an inverse from its predecessor, the somewhat maligned 4th Edition), and Larian, for the most part, opted to allow players to bypass this element of the game by making the difficulty of the game largely modular. For context: Characters recover all of their hit points and resources on long rests and specific resources on short rests, the latter of which are limited to two per long rest. However, there is zero pressure to complete quests within a set number of long rests, and outside of a very small handful of specific and fairly telegraphed scenarios, it did not seem to me that players were restricted from resting at all.

By fairly telegraphed, I mean things like: If an inn is burning in front of you and you long rest, you may return from your camp to see the inn reduced to ashes, locking you out of certain quests in that area. Another time, a companion outright told me there would be consequences if I returned to camp. Conversely, there are things that within the story are treated as quite urgent, but have no in-game timer attached to them. Given how direct the quest log can be already, I wish the game had simply outright stated what elements were time-restricted and what elements were not.

Certain areas did prevent me from taking long rests or going to camp (which lets you swap out party members), but from my post-game testing you could almost always simply leave the area, long rest, and return with no consequences. The ability to swap out companions with ease also made the amount of resources at my disposal feel extravagant, and I averaged roughly one long rest per level in the second act of the game. The result is a difficulty curve that is almost entirely dictated by the player’s own restraint. For players who have some experience with CRPGs, I would definitely recommend playing on Tactician difficulty. Compared to Divinity Original Sin 2, for example, where the difficulty curve spiked later in the game, Baldur’s Gate 3 had the opposite problem: Past the first level or two, where characters are noticeably frail, sailing was too smooth. In fact, the one chunk of the game where I was explicitly warned that going to camp or long resting would forcibly progress certain questlines, perhaps in ways I wouldn’t want, was my favorite section of the game. It hit just the right difficult balance, forcing me to conserve resources and encouraging me to play smartly and tactically.

Another mark against the pacing of this game was that I hit the level cap extremely early into my adventure. By hour 44, I was already max level, meaning that I spent the remainder of the game (almost half of my playtime) at the same level, gaining no new abilities, spells, or feats. The game is extraordinarily generous in allowing you to respec characters, but with seven-plus companions available to me throughout the game and 40+ hours at the level cap, I ended up swapping out companions often and re-specing a couple just so I could log playtime in more classes by the end of the game. Sadly, despite my best attempts to remix my characters, combat had turned rote. Some unique powerful, legendary-tier magical items introduced some spark into the mix late in the game, but not quite enough to rectify the early level cap.

The most damning thing about the character-building options in Baldur’s Gate 3 is that unlike some other CPRGs of recent memory—Solasta: Crown of the Magister and Pathfinder: Wrath of the Righteous come to mind—where I was immediately excited to start another run with completely different builds in mind, I had almost no desire to immediately start a new file. For some people, this level of character customization could be completely fine, or even overwhelming. For me, however, it was quite lacking, and hitting the level cap so early was disappointing. There are a handful of builds that are possible only in this game—a combination of rules changes, class and feature changes, new status effects, and special magic items (e.g., wet status + Tempest Cleric)—so I anticipate returning at some point for some shenanigans, but the fire isn’t immediately there for me like it was for some of Baldur’s Gate 3’s contemporaries.

I titled these sections as I did because, ultimately, I believe a large chunk of these issues stems from Larian’s shackling to the 5th Edition system. Larian has tweaked the system to accommodate the strengths of a video game developed in a three-dimensional space, but it wasn’t quite enough to push the gameplay into truly engaging territory. Consistent pathfinding issues, camera wonkiness, difficulty pulling my party into initiative, limited build options, and a too-easy difficulty curve hurt my experience.

While I believe these drawbacks will be significantly more palatable to beginners, they impacted my experience enough to warrant mention as notable flaws.

I Am Scum

Baldur’s Gate 3 has ignited a fiery discussion about the merits of… save scumming! (No, not that other controversy.) Save scumming has always been a part of games, but the divergence between tabletop D&D (where retconning is very rarely done, save for extreme instances that are for the betterment of everyone’s enjoyment) and video game D&D has generated a divide.

Some say that in the spirit of the tabletop experience, you should let the dice decide your fate. Others are firmly on the other side, mashing the left mouse cursor to roll, casting guidance, and F8-ing repeatedly, until they get the outcome they want. I’m not here to tell you how to play a game, especially a single-player one where your experience affects no one’s but your own. If you want to save scum, you should—though I would personally recommend rolling with the punches at least a few times on your first go-around. The game can react in some very clever ways that you might not expect. (It does, of course, often resort to violence. But such is the nature of D&D.)

All that said, there are two elements in Baldur’s Gate 3 that irk me about its approach to rolling dice, and I do believe that a strange implementation on Larian’s side here has certainly incentivized more people to save scum than usual.

The first element is a feature ubiquitous in almost every CPRG I’ve played save for Baldur’s Gate 3: the ability to choose which party member will roll a skill check (a superscore, essentially). In this game, only the character who initiates a conversation can roll skill checks during dialogue. (Typically, this will be your player avatar, though sometimes a cutscene will choose the character involved based on some sort of distance measurement, which is irksome.)

In tabletop, everyone is aware of their character’s own strengths—the Bard will (or at least, probably should) take the lead in conversations, with their Charisma focus leading to great bonuses to Persuasion or Deception, in the same way the Barbarian should probably be the one rolling to break down that wooden door. Because Baldur’s Gate 3 doesn’t present that option, I ended up playing as a Paladin specifically so I could have my avatar initiate conversations without hamstringing myself in ways that would never happen in actual tabletop play. Basing my class selection on this reason felt restrictive and unnecessary.

Because of the way character building works, characters will generally only have one good mental ability score (one of Intelligence, Wisdom, or Charisma). Often, I’d be in a dialogue sequence and see options for Arcana or History or Religion—Intelligence skill checks that my Tav (the pre-generated name of choice for a custom player avatar) was awful at. If I had the prescience to save beforehand, I was presented with a choice—potentially roll with the outcomes, or reload to see if I could gain some sort of lore or plot-related information that would inform my playthrough. Being locked out of having a better chance to experience more of the lore of this world and story seemed like a strange decision that frustrated me to no end, especially since it is so easily available in other games.

At the table, a Dungeon Master (DM) would generally prompt the group, and everyone would have a chance to participate, but this isn’t the case here. Characters tended to be pretty good about interjecting on topics especially relevant to them—Lae’zel would have quips about githyanki-related topics, Shadowheart with religious worship, Gale on topics of arcane magic—but you still have to roll for things that are gated behind skill checks. I wanted to see if I could glean that additional extra lore or knowledge. I wouldn’t be surprised if this was implemented at some point via a patch given how easy it seems to enable and how ubiquitous it is as a feature across the genre, but it was a point of contention that irritated me numerous times.

The second element that may aggravate some stems from the underlying philosophical design of 5th Edition, which is that character-building choices tend not to shift the odds in your favor as strongly as it would in other games. Even a Charisma-based character will likely spend most of the game with their Persuasion bonus hovering between a +6 and a +8, and the d20 provides a significant amount of variance in whether you succeed or not at most story-relevant checks. (Most of the lower DC checks in this game tend to be superficial as opposed to critical story beats.)

The end result of this in Baldur’s Gate 3 is the creation of a living, breathing world, where you are presented with choices of enormous consequence. But the outcomes of these choices are not just informed by the alliances you have made, or the attitudes you present. They can feel, in large part, adjudicated by the highly variable outcome of a d20 roll. For some, that might be a feature, crafting a unique journey beholden to the luck of the roll. For others, it might feel a bit too high variance, where it feels like your decisions and build are hardly participating in the story being told. I can understand the complaint, though as said previously, you might be surprised at how amenable or interesting the failure states are, though they are obviously not going to be as flexible or workable as anything a human DM may present.

In the end, save scumming is easy, and having to F8 every so often might not be a detriment to you. Failing a skill check isn’t the end of the world, and it still leads to interesting outcomes. I didn’t feel excessively driven to save scum, but I did occasionally reload conversations because I wanted the right character to engage in the skill check presented. This was at times an aggravation, and in a strange way felt as if the game was actively preventing me from learning as much about its world as I could, but no harm no foul either way. Play as you want—Baldur’s Gate 3 is robust enough to provide satisfactory outcomes for all styles of players.

Note: The following section contains general spoilers for my impressions of the final act. If you want to skip ahead, go to “Final Thoughts” for my score and conclusion.

Act 3 Malaise

As mentioned earlier, Baldur’s Gate 3 has three acts, and all three of these acts had a distinctly unique feel to them in terms of setting, which I enjoyed. (I won’t get too much into the specifics of each act for spoiler reasons.) Act 1 felt very polished, with so much effort put into a ton of nuanced interactions that all felt handcrafted. Act 2 immediately presents the players with a specific problem, a specific goal, and says, “Find out how to deal with this,” an open-ended challenge that I had to rise to the occasion to solve. Act 3, unfortunately, falters noticeably in comparison to its earlier brethren.

CRPGs becoming less interactive, less reactive, less polished, and more buggy is quite common—a problem that plagued Divinity Original Sin 2, both Owlcat Pathfinder games, and numerous others before. As the branching web of decisions widens, it becomes harder and harder for the game world to keep up, and I felt this acutely in the final act. There’s a reason a large chunk of those charming character interaction videos that pop up in your Youtube feed (or maybe that’s just me?) are from Act 1—as the portion of the game that was in Early Access for years, it is by far the most fine-tuned.

It isn’t that the content in Act 3 is bad—on a core level, the stuff is good—but things feel uneven and worse, outright missing. Unique dialogue options based on race, class, background, or companion become increasingly sparse compared to the earlier acts. Companion quests often come to a dramatic close—for some, but not all. Some join so late that their addition, while welcome, almost amounts to comedic relief, while others who have been there from the beginning have a roughshod, thrown-together ending. This portion of the game also suffers from previously mentioned performance issues, not to mention more bugs and a general lack of polish.

I enjoyed the main and companion quests in Act 3, but even then there were character moments and narrative beats that I thought would have more meat to them (or exist at all) that did not, and it did feel like some content was obviously omitted last-second. In particular, some decisions that I had committed to early in my playthrough—which seemed quite important at the time—ended up being of almost no consequence at all, which damaged my belief that my choices really “did matter.” I personally like it when a broad narrative slowly tapers into a dense conclusion, but Baldur’s Gate 3 didn’t quite stick the landing here.

The epilogue—or its lack thereof, rather—feels particularly notable. I genuinely couldn’t believe that there was no ending slideshow recapping my key decisions or the fates of my companions, another CRPG staple. For a game that has been touted for its reactivity, not seeing anything come of the choices I made in the future of the world of Baldur’s Gate was a bummer, though not enough to wipe away the fun I had for the previous 80+ hours I’d invested into the game. This is another element that I wouldn’t be surprised to see added via a future patch or edition of the game.

Final Thoughts

My first playthrough of Baldur’s Gate 3 was a marvel: beautiful, enthralling, and bursting with content. Larian Studios has successfully created a CRPG that welcomes players who are not already part of the genre’s existing fold. An 80+ hour experience that’s gripping from start to finish, Baldur’s Gate 3 fills a vacancy that has not been truly filled since The Witcher 3. It’s an epic, reactive fantasy RPG in which you almost never run out of things to do.

Its gameplay isn’t without fault, and it lacks the true ceiling-busting build freedom of some of its CRPG brethren. It suffers from its final act and strains under the weight of its own ambition, particularly when the illusions of choice begin to reveal themselves as just that. But despite its faults, Baldur’s Gate 3 has rightfully earned its praises.

Those who are deeply familiar with D&D 5th Edition may have a heightened sensitivity to some of its shortcomings, but make no mistake: Baldur’s Gate 3 is a triumph and any fan of RPGs would do well to give it a roll.

Score: 9.0/10

Miscellaneous Notes and Thoughts

- The simple ability to switch characters/superscore for skill checks, and the addition of an actual pause (not to pull up the load/save menu, but just pause and be able to look around the battlefield and queue up actions) would add a half point to my score, instantly.

- Inventory management wasn’t a problem for me, but it isn’t the smoothest or most intuitive UI either.

- The only companion whose class I outright changed was Halsin (of bear sex fame), who went from Druid to Monk. It’s hard to comment too much on “balance” given the very forgiving nature of this game as far as difficulty goes, but I can say that I never felt that a given class felt too weak to play through the game.

- I was able to clear the game on Balanced without resorting to any sort of specific broken item-class build or things of that nature (of which there are a handful). Many control spells were reduced in their duration from tabletop, so I found myself utilizing a good spread of spell types. I’ve read that you can engage in quite a bit of minionmancy—having a ton of conjured summons that fight by your side—but I never felt that was necessary personally.

- The pace at which I found or received magical items felt good. Nothing came along that I felt was absurdly overcentralizing until the late-game, where things tend to go out the window anyway.

- I don’t believe it’s fair to review games based on personal expectations or knowledge of Early Access changes, developer statements, etc., so I tried to empty my head of those as much as possible during my playthrough. I will, however, note that there is a significant amount of cut content relating to Act 3, and even developer statements from as recently as June that are contradictory to the game in its release state. Early Access enjoyers will note that the “Daisy” element of the story has been revamped entirely. Will there be an “Enhanced/Definitive Edition” a la Divinity in the future?

Some Tips Before You Go

- Save often. Again, you are free to play in any way you want, but I do recommend creating a new save file at least every 30 minutes just in case something buggy happens, or you find yourself in a particularly untenable situation that functionally soft-locks your progress. I mentioned that the difficulty can be very modular, but that doesn’t mean you can’t get stuck.

- If you’ve cleared an area out, it might be worth it to long rest—there are occasional dialogue scenes that only happen on long rest, and you can miss them. It’s definitely possible to go through large chunks of this game on a single long rest, but you’re (generally!) not on the clock, so don’t worry too much about long resting.

- Seriously: Speak with animals and speak with dead. I didn’t do it on my first playthrough, and now on my second, I’m catching up on a ton of interactions I missed out on. As rituals, they can be cast for free with no resource cost, and when speak with dead is active, corpses you can talk to are highlighted in green. Kill a boss? Chat them up!

- I really do recommend Tactician difficulty if you have any familiarity at all with tabletop 5th Edition or CRPGs in general.

Huge video game, comic book, and anime fan. Spends way too much time watching things he doesn’t like. Hates Zack Snyder. Mains Falco.