Major spoilers ahead for the God of War (2005–2022) franchise.

Over the years, a role I’ve assumed here at The Punished Backlog is that of “Old Games Guy,” since I frequently play — or, in many cases, repeatedly revisit — games from generations’ past. I do this not simply for the joy of it (though I often do enjoy these artifacts): I also seek to understand where gaming used to be and how much the medium has changed. In some cases, however, playing an older title — even a once-vaunted one — can showcase just how far we’ve come.

Most recently, I gave 2010 PlayStation 3 title God of War III a shot (more specifically the 2015 PS4 remaster), and the results have been… illuminating, to say the least. I went in expecting a fun but cringey character action experience where the dialogue and treatment of women wouldn’t hold up especially well. What I found was a kind of experience that not only would be received very differently now, but also represents a time in gaming I’m glad we’ve strayed away from, at least somewhat.

The Cruelty Is the Point

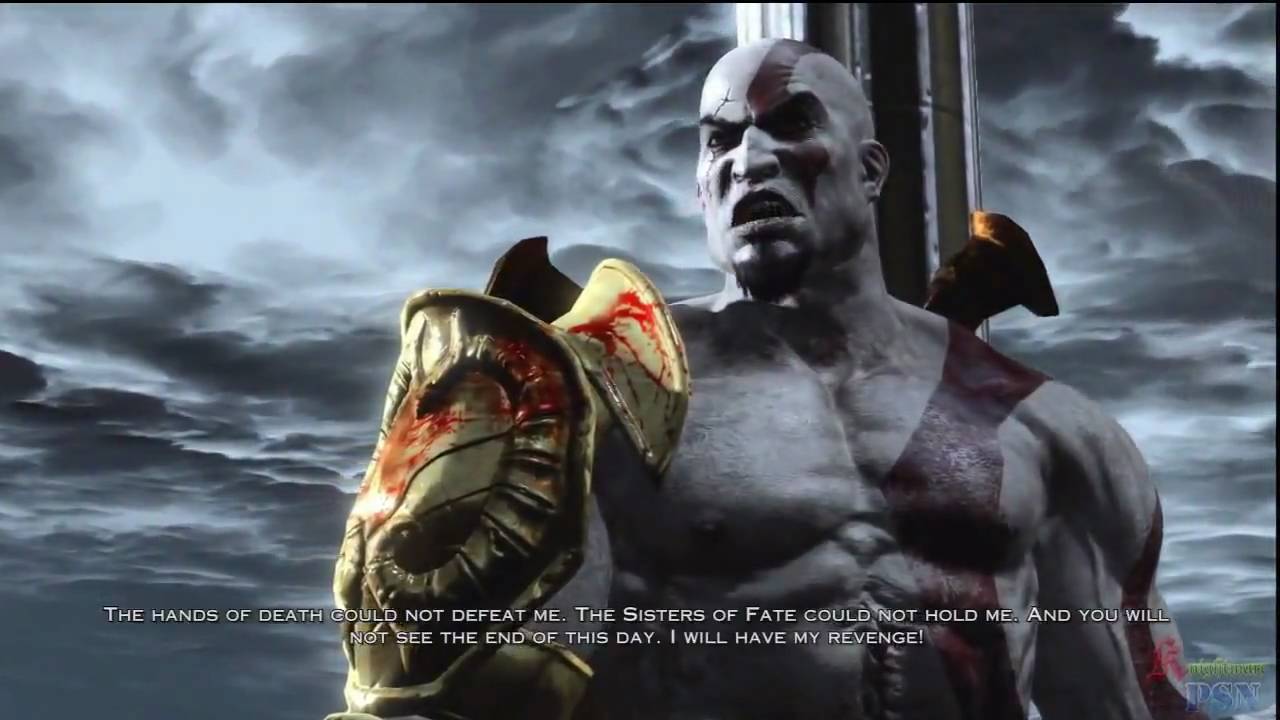

For those unfamiliar with the God of War franchise, the earliest editions of the series (2005–2010) focus on Ancient Greek demigod Kratos, also known as the Ghost of Sparta, who seeks revenge against the gods — particularly his father Zeus — for their continued deception and the harm they’ve done to him and those around him. In the first game, Kratos kills Ares for tricking him into killing his own family in a failed attempt at making the Ghost of Sparta the ultimate warrior. The sequel, God of War II, sees Kratos vowing to join the Titans in taking down Olympus for destroying his home of Sparta and killing his fellow soldiers. God of War III continues this part of the story, tasking the player with killing each and every Greek God as part of a broad, bloody quest for vengeance.

The third mainline game in the series takes the brutality and intensity of its predecessors and ratchets up the stakes and gore. The player feels Kratos’ bloodlust not just in every cutscene, where he aggressively states over and over again that he will stop at nothing to exact his revenge and that anyone getting in his way will perish, but also in the gameplay. These God of War titles do indeed feature smooth action mechanics and a variety of approaches to combat, but they also allow (and actively encourage) the player to kill enemies in the most ferocious of ways, including slamming heads into walls, ripping bodies in half, gouging eyeballs, slashing throats, and the like.

It’s not in any way unusual for action games to revel in this kind of violence, nor is it in any way a thing of the past. The Mortal Kombat franchise continues to get new entries every single console generation, and each is more gory and disgusting than the last. 2025 alone will see the release of three different Ninja Gaiden games, all with their fair share of bloodsplatter. Doom: The Dark Ages came out just a few months ago. For whatever reasons, gamers love blood and gore, and can’t seem to get enough of it. The first God of War in 2005 leaned into that desire, and its sequels further capitalized on it.

But unlike the largely campy nature of bloodfests like Doom or Ninja Gaiden, the violence in these games — particularly in God of War III, the subject of this very piece — feels different. More than simply visceral, the actual killing comes off as especially cruel and nihilistic. Kratos frequently murders those literally begging for mercy, and appears to feel absolutely nothing whenever he does so. In some cases, people — not even gods, just regular human beings — shudder and scream at the very sight of him, knowing he will absolutely cut them down if it benefits him, even marginally.

There’s not even a tinge of sadism or hokey Duke Nukem swagger to Kratos’ never-ending massacres; he just kills and kills and kills without remorse or thought. Even the clear negative consequences of his deicides — constant dark rain without Helios’ sunshine, the spread of a plague after the death of Hermes — seem to completely elude him. He barely reacts at all to these developments even as they unfold around him.

It’s not just the nature and framing of Kratos’ violence that makes God of War III feel ancient. If nothing else, consider the game’s egregious, constant assault on women. Among all the vile things this game does, the constant violence it inflicts upon its women — both physical and sexual — has to be the most indefensible.

It’s not so much that Kratos enjoys or even takes pride in the carnage; he seems to do it purely out of a sense of ruthless pragmatism, with no regard for the well-being of anyone else. In one instance in Olympia, the player must climb alongside a narrow path where an innocent man is hanging for his life, and you have to throw him off the ledge just to get through, and Kratos says nothing as it happens. In another moment, Kratos frees a woman imprisoned by Poseidon who at first calls for help, but then relents the second she realizes her savior is the Ghost of Sparta. In order to advance past this part of the main story, the player must forcefully shove this woman multiple times until using her as a wedge to keep a door open. Much like No Country for Old Men’s Anton Chigurh, Kratos kills certain people simply for inconveniencing him.

In these games, Kratos is humorless, joyless, emotionally repressed, and enraged at all times. He never so much as cracks a smile or sheds a tear in God of War III. Instead, Kratos constantly wears a snarling frown that only wrinkles further with each battle. He’s not especially stoic or calculated, either; he’s a reckless killing machine on a constant quest for blood, and nobody, no matter how innocent, weak, or defenseless, deserves protection from his wrath.

Moreover, the main source of his trauma — the death of his wife and children, whose ashes he must wear upon his body at all times — fails to instill any sense of compassion toward the suffering of others or concern for justice outside of his realm of understanding. Kratos is nothing more than a one-dimensional killer who can’t see past his own rage. For a character who defined the PlayStation brand for years and served as a broad video game icon of the PS2 and PS3 eras, I was struck by the reality that Kratos basically has no personality at all, at least not one that comes through in meaningful ways.*

Ultimately, that’s what makes God of War III’s violence particularly unsettling: Kratos has too much of a particular backstory and too much dialogue to be a silent, nameless cipher for the player’s experience, but he lacks the humanization required to make his endless killing feel interesting, important, or even particularly justifiable. Even though God of War III’s portrayal of the Gods of Olympus makes them unsympathetic figures, Kratos still barely has a compelling motive other than exacting a vendetta. Outside of a few small moments of tenderness for the young Pandora — whose father he murdered earlier in the game — his actions lack any semblance of nobility or commitment to a broader cause. It’s simply a tale of one demigod’s particularly intense grievance. Despite his self-sacrifice at the very end, he’s not really looking out for the little guy; he’s just wreaking havoc and committing endless murder.

*His protectiveness of Pandora is a rare exception, and even then, this doesn’t appear until late in the game and feels like an awkward pivot more than character development. There’s also the final hour’s half-hearted attempt at showcasing Kratos’ regrets while he wades through The Darkness, but this sentiment is immediately undercut by his brutal, bare-fisted beatdown of Zeus just minutes later.

Unforgivable

It’s not just the nature and framing of Kratos’ violence that makes God of War III feel ancient. If nothing else, consider the game’s egregious, constant assault on women. Among all the vile things this game does, the constant violence it inflicts upon its women — both physical and sexual — has to be the most indefensible.

Nearly every femme or femme-coded being in this game has their bare breasts exposed at all times, including the harpy and gorgon enemies, all of whom Kratos obliterates the second he doesn’t need their assistance. Aphrodite, the Greek Goddess of love and desire, offers herself as a sexual prize to our surly antihero the instant she sees him (she is, of course, flanked by two other naked women), allowing the player to participate in an off-screen sex mini-game (these, regrettably, are a staple of the franchise’s early entries) both before and after Kratos kills her husband Hephaestus. Outside of opening up a portal for Kratos, the goddess’ presence serves no other narrative purpose.

Oh, remember that prisoner Kratos crushed simply to open a door? She was topless as well, barely covering up her naked body as the Ghost of Sparta forcefully thrust her into her own bloody demise. Hell, one of the only fully clothed women in this game is the Goddess Queen Hera, and the game depicts her as a bored wine mom. Kratos eventually kills her by snapping her neck, and not soon after uses her corpse as part of a balancing puzzle. Outside of Pandora — who, again is still basically a child — women in God of War III exist largely as objects of loveless sexual desire or victims of the most brutal, cold-blooded murders imaginable.

A Softer God… Eventually

One might argue that the cruelty of Kratos in God of War III is simply a byproduct of that era of gaming and nothing more. But even if you believe there’s fundamentally no difference between how God of War III sold its vision of masculinity and violence and how other games of that era did — and I truly believe there are notable distinctions — over the past decade, the folks at Sony Santa Monica certainly seemed to believe that Kratos needed a refresh for a new generation.

Released in 2018, God of War took the franchise in a completely new direction, abandoning Greek mythology in favor of Norse mythology, updating the control scheme from a fixed-angle action free-for-all to an over-the-shoulder view with lock-on mechanics, and perhaps most notably, giving Kratos an entirely new life.

While Kratos is literally the same man from the previous games, he’s fathered a son with a Norse woman (whose magical past he apparently had no knowledge of) and seeks to turn over a new leaf, using his godlike abilities for hunting and self-defense only. Rather than a tale of bloody revenge, God of War (2018) instead tasks Kratos and his young boy, Atreus, with scattering the ashes of Fey, Kratos’ wife and Atreus’ mother, only to find themselves ensnared in another clash of gods.

Critics (and many folks at The Punished Backlog) adored this fresh take on the GoW formula, not just for its updated mechanics (fixed-camera views in AAA games had gone the way of the Dodo at this point), but for its exploration of grief, the challenges of fatherhood, and the very notion of violence as a tool, even in self-defense. Personally, the narrative side of things didn’t really land with me for a variety of reasons, though mainly I objected to the notion that Kratos was some remarkably changed man just because he keeps saying he is. In terms of the main actions the player takes in God of War (2018), you’re not really doing anything different than you were in previous games: killing hordes of mythical enemies in increasingly brutal ways, murdering gods, and opening boxes by punching through them.

That said, after replaying God of War III, my stance on the 2018 reboot has softened, though not completely reversed. As I said before, the framing of it all really does matter. This new-and-improved Kratos still spends a lot of his time yelling at his son, pouting, and whacking his magical axe at people and stuff. But he’s also motivated largely by a desire to fulfill his wife’s dying wishes and protect Atreus from danger, even if he struggles to demonstrate his love and conceal his dark past. The gods are no longer targets of his wrath; they’re threats to his child. Sure, Kratos’ frequent admissions of shame and regret still fall flat when he’s still there mostly to kill, but there’s at least some acknowledgement that he’s tried to move on from his past self, even with mixed results.

The 2022 sequel God of War Ragnarok — as well as its excellent Valhalla DLC — actually succeeds in taking Kratos to task for his misdeeds, forcing him to truly confront his violent past and make amends where he can. Personally, my favorite cutscene in Ragnarok involves the Nornir (the Fates of Norse mythology) chastising Kratos for his half-assed attempts at redemption, mocking him for simply “feeling bad” about killing gods even as he still does it. Moments like these recognize the faults of the franchise’s past and what it really takes to move forward. Sony Santa Monica couldn’t simply tell a new story and forget the previous ones happened; much like Kratos, they had to make amends of their own.

A Sea Change

Notably, God of War III released during a fascinating era for violent video games. The best games of the PlayStation 3/Xbox 360 era offered players massive visual and technological leaps from the prior generation, and as a result the blood and gore of that era stuck out in particular ways.

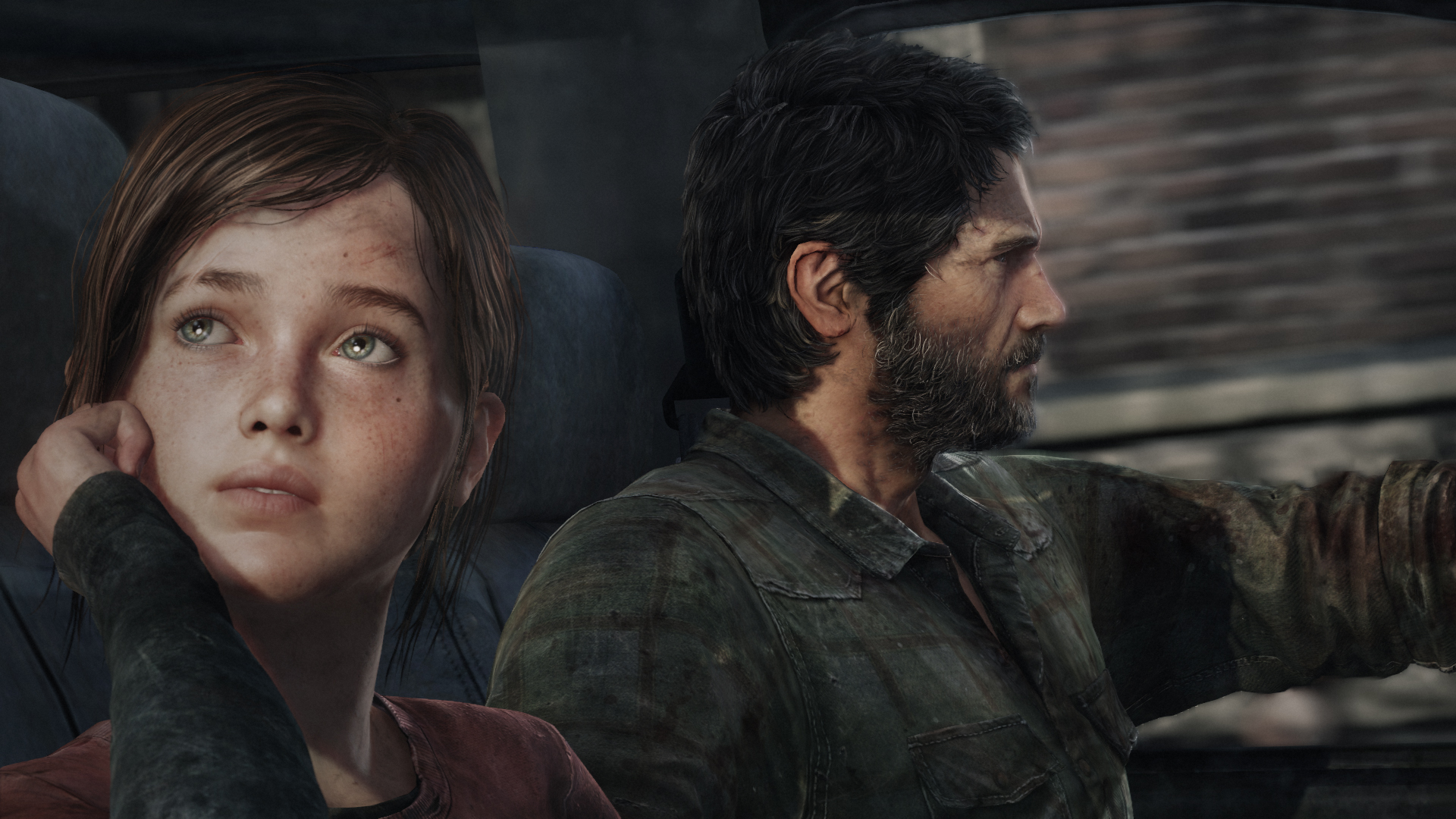

Simultaneously, though, a number of high-profile games and franchises during those years attempted — with mixed results — to comment on the nature of violence in digital spaces, in some cases even criticizing players and the medium itself for glorifying such carnage. While a number of games only hinted at such subjects (Uncharted 2: Among Thieves, Gears of War 3, Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare), a handful fully embraced it as part of a more focused commentary (Hotline Miami, Spec-Ops: The Line, The Last of Us, Red Dead Redemption). Even AAA games less interested in saying much about violence still wove in more detailed narratives that offered players choices about whether to engage in combat at all (Fallout 3 and New Vegas, the Mass Effect trilogy). The age of the mindless killing machine power fantasy, while not dead in any real sense, at least felt challenged, if not partially dormant.

Even amid this supposed sea of change, God of War III’s approach to emotionless, rage-fueled brutality was still met with incredible praise. The original 2010 PS3 release garnered a 92 on Metacritic, with Game Informer’s Joe Juba saying in his 10/10 review, “Not even in my wildest dreams could I have imagined such a powerful, cinematic, and breathtaking conclusion to the saga of the Ghost of Sparta.” While reviews largely criticized the game’s simple and overly cruel narrative, they still lauded the title’s gory combat, epic boss battles, and breathtaking visuals.

In fairness to them, I can’t even disagree with much of the positive sentiment. The combat feels good. The game ratchets up the challenge at every turn, and the boss battles offer some incredible cinematic moments (the fight against Cronos, in particular, is sublime). The fixed camera certainly feels like a relic of its time, but it serves a distinct purpose, as it forces the player to gaze at the stunningly detailed backdrops and level architecture. And while the game is mostly a gauntlet of murder and brutality, Kratos does ultimately sacrifice himself at the end to prevent any other Greek Gods from accessing magical power, instead leaving it to the common people of Greece, so there’s at least a small attempt for Kratos to rectify his misdeeds.

Still, God of War III’s pros simply don’t outweigh the cons, at least not in 2025. Sure, it doesn’t necessarily tell the player that Kratos is some kind of hero, but he’s not even an interesting antihero. Playing as this monster often made me uncomfortable, but not in a way that felt profound or intentional. Given Sony Santa Monica’s different approach with the recent Norse God of War games, I refuse to believe they originally wanted to make God of War III some kind of meditation on the nature of petty, dangerous men. Kratos was supposed to be a cold-blooded badass, and I suppose the meaning of that moniker is different now than it used to be. It certainly is for me.

The Past Is the Past

I’ve previously written about my preference for ultra-violent games to embrace a bit of silliness and melodrama instead of trying to present ambitious and nuanced stories. I’ll take the bloody, nonsensical charm of a Doom game over the pious, misguided sentiment of a BioShock Infinite. Give me Devil May Cry 5’s silly, demonic horniness over The Last of Us Part II’s fake-deep misanthropy any day of the week. Hell, after first playing God of War (2018), I thought the same thing: If Kratos is just going to kill gods and rip monsters to shreds with his bare hands, spare me the sob story.

Clearly, God of War III has challenged this notion I’ve held dear for so long. Maybe it’s a good thing if games at least attempt to say something about a players’ penchant for bloodshed, even if the message comes off as messy. Maybe the pinnacle of AAA experiences can only be reached if such explorations of violence are at least considered, if not fully embraced.

Sony Santa Monica couldn’t simply tell a new story and forget the previous ones happened; much like Kratos, they had to make amends of their own.

I’m not saying future Mortal Kombat and Ninja Gaiden games need to do this, either. Mindless killing of random creatures and robots has (for better or worse) been a cornerstone of video game development for decades, and I think it’s fine if we keep making those. But if you’re going to try and make a real story with real characters, you have to be smarter about it.

The Kratos of old should never make a return. Sometimes, it takes replaying a game from a different time to remind you of how much has actually changed.

Sam has been playing video games since his earliest years and has been writing about them since 2016. He’s a big fan of Nintendo games and complaining about The Last of Us Part II. You either agree wholeheartedly with his opinions or despise them. There is no in between.

A lifelong New Yorker, Sam views gaming as far more than a silly little pastime, and hopes though critical analysis and in-depth reviews to better understand the medium's artistic merit.

Twitter: @sam_martinelli.

The only criticism I would add is Athena isn’t depicted sexually either. If anything, that was the only god he cared about and he accidentally strikes her down. In the mainline series, she was the conscious foil for Kratos’ decisions. There’s a nice role reversal of them by the end of the third game which is unexpected from where she started, but very much on course with her development by the end of the trilogy. Kratos is a solider at the end of the day, but you don’t get much read on how this shaped his world view until God… Read more »