A Look Back

This month marked 30 years since Tekken entered the world, and the series still remains the king of 3D fighting games. The proof is in the releases: eight mainline entries, seven spinoffs (including the Tekken Tag Tournament games), and several media interpretations, with the most recent being Tekken: Bloodline on Netflix. That’s pretty good for an original fighting game series, especially one that shares its birthday with the very first PlayStation. To understand the importance of Tekken, though, you need to start at its origins, and that starts with competition.

The Start of Something Special

The year was 1994 and Sony was getting ready for their first console to be released. At the same time, Sega was getting ready to unveil the Sega Saturn. At the time, Sony saw Sega as huge competition, since both companies were launching consoles based around 3D graphics. As timing would have it, Sega had already launched Virtua Fighter in arcades in December 1993. It was the first 3D fighting game to be released and would go on to be one of Sega’s best selling arcade releases.

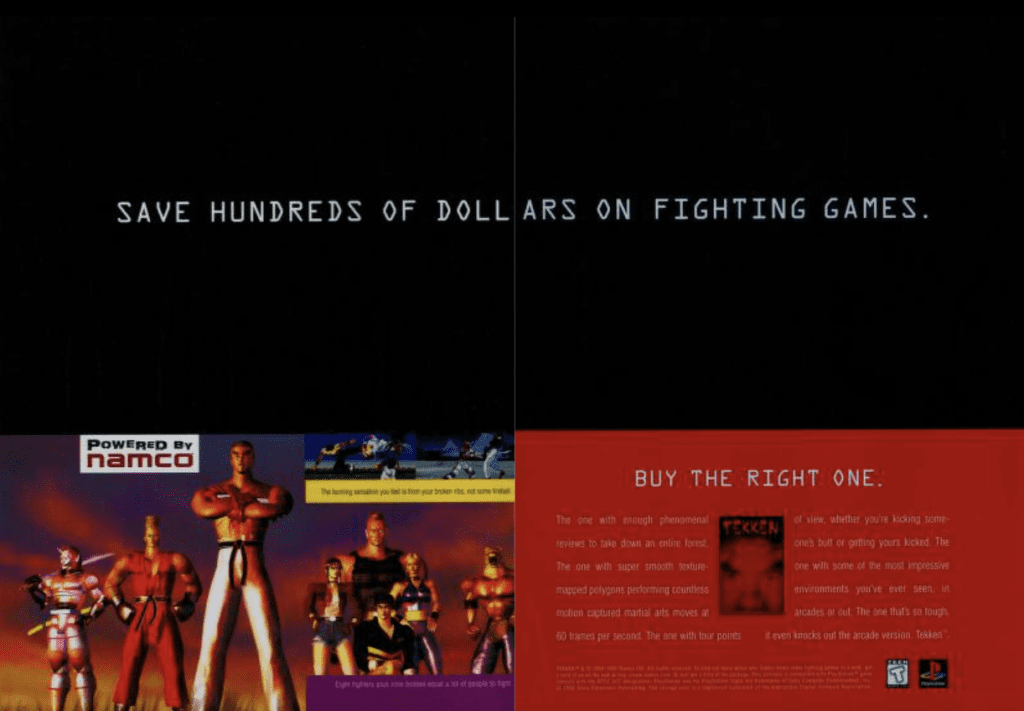

Sony wanted to compete at all costs, so they partnered up with Namco Entertainment, bringing in Virtua Fighter designer Seiichi Ishii. With the support of both companies, Tekken would come out as a big hit in arcades in 1994 and then on PlayStation in 1995, with such success helping to establish the close relationship between Sony and Namco, and forever changing fighting games in the process. An original ad for Tekken plays up this rivalry further, stating, “Save hundreds of dollars on fighting games. Buy the right one.”

Tekken had two distinct features: there were no ring outs and it was the first fighting game where each limb was assigned a button. Emphasizing a focus on combo development, players can juggle, smother and crush their opponents into submission using the stage walls to their advantage.

As history goes, the first two games were received remarkably well. Tekken 2 released in 1995 for arcade and 1996 on console, going on to sell 5.7 million copies. Moreover, it gave Sony the boost it needed to take a significant lead in the console wars. For perspective, it came out the same year as Resident Evil, Crash Bandicoot, and Tomb Raider. All four of these games would eventually be among the PlayStation’s twenty best sellers. With such results, Tekken 3 was an inevitability and would go on to become the series most important release.

The Legacy of Tekken 3

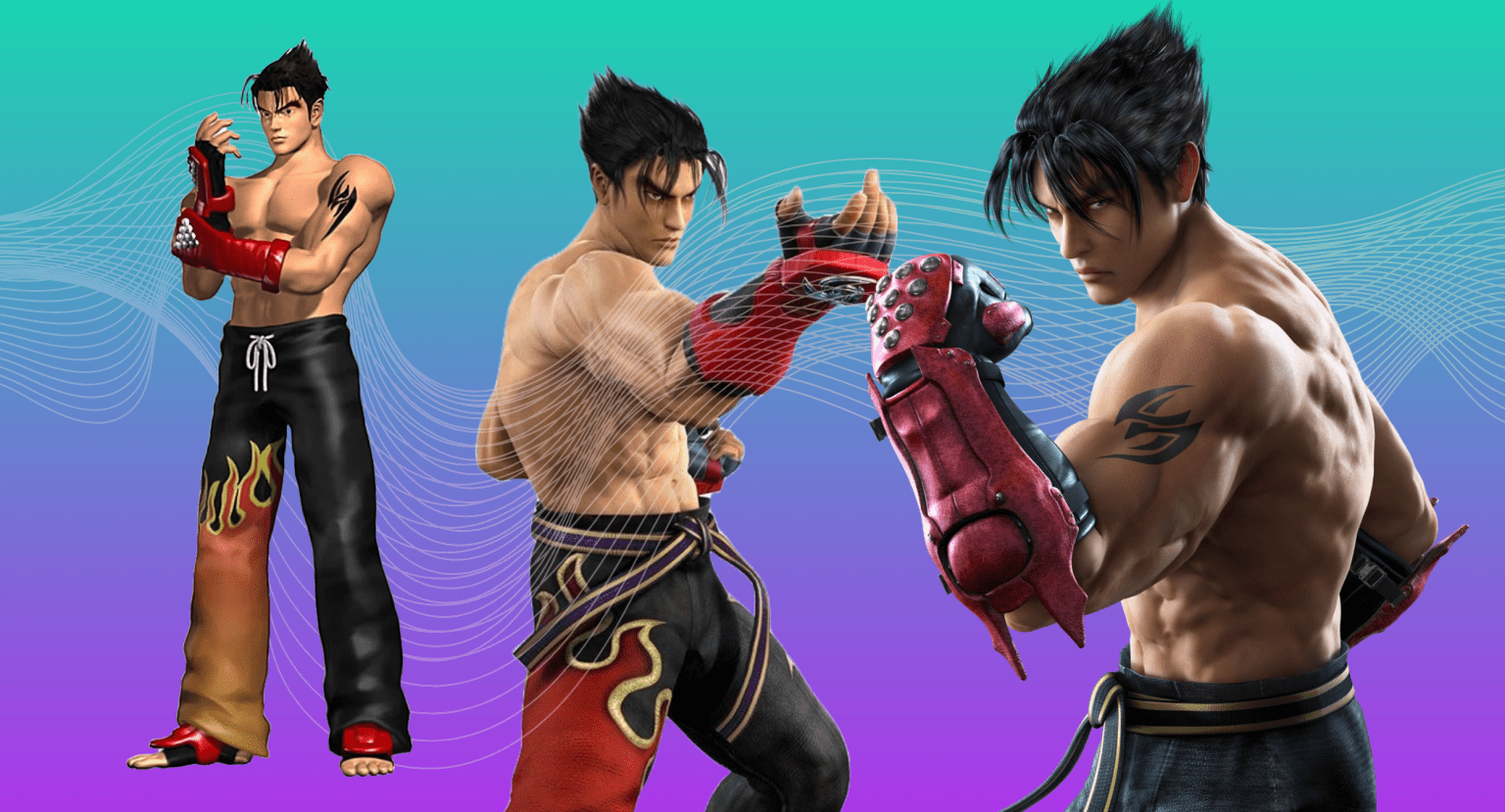

It had only been three years since Tekken was created before its third title was released in 1997. The DNA that would become modern Tekken was established in this entry, from music to gameplay, as well as the introduction of Jin Kazama, who is the most recognizable character in the franchise besides Heihachi (sorry, Kazuya fans). Another thing to note is it’s the first game from current Executive Producer, Katsuhiro Harada, as director (one of three credited).

Composers Nobuyoshi Sano and Keiichi Okabe chose “big beats” as the music style of the game under Sano’s suggestion. If you have no idea what that sound is like, you can pull up the Chemical Brothers song “Block Rockin’ Beats” or try to recall the background music played throughout most of The Matrix. The techno enthused sound was a shift from traditional fighting game music which ranged from upbeat synth and percussion to ambient. The most popular song from this soundtrack is “Jin Kazama,” which isn’t surprising as it was the iconic titular character’s breakout appearance. It even received a nostalgic nod in Tekken 8’s arcade mode.

With an eventual 20 year in-game time skip between Tekken 2 and Tekken 3, a new cast of characters was expected. These new faces included Jin, but also Hwoarang, Ling Xiayou, Panda, Eddy Gordo, Forest Law and Bryan Fury. With that in mind, the modern King as we know him also appears here (King I dies under mysterious circumstances), and everyone’s favorite grizzly bear Kuma II enters the fray (he’s the son of the first Kuma, who dies of old age).

Gameplay That Defined a Genre

Movement. It’s what keeps us going and reminds us we’re alive. From a simple tapping of a finger or the blinking of an eye, each one of these smaller moments builds to a larger orchestration of what we can achieve with our bodies. For Tekken 3, it was one movement that changed what we thought was possible in fighting games: sidestepping.

This one dynamic movement suddenly evolved a genre and cemented this game’s legacy. When we talk about movement, it’s all math at the end of the day—how fast can I run a mile, how far can I jump, when will I arrive at a destination? While this addition seems normal today, it completely changed what could be done in the game. Characters could now angle around every aspect of the stage.

It started off as a Kazuya Mishima exclusive move in Tekken 2, and became fundamental to how all characters move starting Tekken 3. In the context of a fighting game, we’re talking about avoiding hits and following up with combos (punishers). In addition, attacks while sidestepping were added, so now you had to worry if an opponent dodged, were they also attacking? With this inclusion, you could now attack while rolling, rising and moving sideways.

While most characters’ moves attacked forward, figuring out which combos had sweeping attacks was critical to catching someone off guard who sidestepped. Unless you were fighting Xiayou… in which case, good luck because all her kicks sweep to the side and will catch you upside the head the minute you drop those hands to move.

Did I mention you could throw sideways? So many new possibilities came from this basic mechanic. Each character had different throws depending on their angle, and I mean every angle. Throwing from the front was different than from the back and that difference extended to throwing from the left side or the right side.

Characters like King took this a step further. As the wrestler of the game he had the longest combo string of throwing and the most throwing combos. If he grabbed you, pray your opponent was inexperienced or watch in real time the total destruction of your health bar by an expert luchador. Now that I mention it, sidestepping attacks were different from left to right too. Given all the new ways to attack, most people were spending hours in Practice Mode just to learn them all, especially deadly move strings like 10 hit combos.

Ten hit combos were greatly expanded in this entry, with multiple characters having more than two sets (Forest Law had six, Jin had seven). With no ultimate attacks to level out one sided matches (save for a few), combos were the great equalizer. Knowing a character’s moveset allowed you to punish an opponent’s mistake, blasting them into mid-air for a quick two piece juggle or catching them off guard for massive damage (back turned, sideways, etc.). Nevertheless, it isn’t common or practical to finish them all the time. I use present tense here to suggest they are still used most often as a way to create spacing or overwhelm opponents when you’re looking for a quick hit. That being said, don’t sleep on them and get caught not guarding.

Lastly, hidden moves. The best way to understand them is by looking at them on YouTube and seeing the cleverness of what players discovered in this new gameplay. A lot of these moves are not documented in any move list and can include things like throws from certain angles, stringing together unrelated combos, and the iconic charged attack follow ups (many of which are in the move list somewhere but some aren’t).

Another example is who can parry and who can counter? This probably applies largely to Tekken Tag Tournament, which was my first experience with the franchise and which famously built off of Tekken 3. While not hidden per se, there are characters who can counter in this entry who will never counter again in later entries. For context, the move lists in this game extend as high as 100+ for some characters, so for there still to be hidden moves speaks to the quality of the code and gameplay.

Getting back to Tekken 3, even design choices from this game are memorable. Iconic examples include King wearing a T-shirt tucked into his track pants, Jin’s gauntlets/gloves (who knows if they’re one or the other), Hwoarang’s dobok vs his biker outfit (traditional with an edgy shift), and the most stylish characters: Ling Xiayou and Eddy Gordo. Xiayou would rock a sleeveless orange qiapo (cheongsam) top with orange kungfu pants. Another outfit would see her wearing a yellow obi (sash) with a blue and yellow blouse, and she is one of the few characters to get three outfits in her first release. Her and Jin have their Japanese school attire fits as the third option. And last but certainly not least, Eddy Gordo. Wearing his iconic yellow and green (for Brasil) capoeira outfit that he still wears today, in total we see him in four fits with two playable and the third, a brown button-down with a black pattern, appearing in later games.

In the end, Tekken 3 was a smashing success, selling 35,000 arcade units (in today’s dollars, these cost roughly $16,000 a machine) and 8.3 million copies on console. Combining all three games’ sales, it was the fifth best selling series on the first PlayStation and Tekken 3 is the fifth best selling PlayStation game of all time. For the critics, 1997’s Tekken 3 is the highest scoring game in the series, sitting at a 96 on Metacritic with the next highest entry being this year’s Tekken 8 at 90. Remember how I said sidestepping came from Kazuya? Well he’s not even in the third game since he got thrown into a volcano (a common expression of love in the Mishima family).

The Post-Tekken 3 World

Following the success of Tekken 3, the franchise would continue to maintain a major presence in the fighting game space for decades. What’s shaped the longevity of this series, though, is its ability to stay consistent. When you pick up a Tekken game, you know what to expect: fast-paced competitive combat, a distinct roster of characters with unique styles, superb stage design, and an adrenaline pumping soundtrack. Throw in the ridiculous character endings as you finish the story mode, and you have the perfect formula. The main story is absurd, but so are those of most fighting games.

For Tekken, the series is about the conflicts that come with power and the ongoing blood feud within the most powerful Mishima family, focusing on Heihachi, Kazuya and Jin. As a result, the roster of characters and their stories revolve around the changes within the family’s struggle and ultimately what side they’ve aligned themselves with at one point or another. What bonds them all is the declaration of the strongest fighter, which can only be determined by beating all competitors in Heihachi’s creation: “The Iron Fist Tournament.”

The design of the series is worthy of the highest of praise, as it is detailed, intentional, and downright beautiful. Each game brings its own stylistic flavor which can be seen in the character design and stages, and heard in the soundtrack.

However, it’s fair to say that since Tekken 4, the team has put more effort into these aspects than the narrative side of things. Katsuhiro Harada, executive producer of the series, admitted as much in a recent interview when discussing the series’ anniversary. While he’s not specifically talking about the fourth entry, fans remember it as the strongest story implementation but also the largest change in gameplay.

Tekken 4 grounded the series in an unseen realism, adding somber distinction to each character in an already dark story. Throw in the most realistic gameplay elements included in the series, distinct voiced over illustrated prologues and epilogues (which became a series staple until Tekken 7), and lastly a physical and mental maturing of the roster. Reflecting on the combat, many have compared this entry to fencing while the usual flow is a fast paced ballet. In the end, the slower paced combat and new realistic elements wasn’t what Tekken fans had grown to love. So, the team went back to what had worked in previous entries and fine tuned some of those aspects.

This Fan’s Favorite

The result was Tekken 5, my favorite in the series. While I outlined what made this game one of the best PS2 releases, it’s important to stress that it took everything that went well in Tekken 3 and combined it with the experimentation of Tekken 4. It’s the first release where customization was added, rewarding fight money for fights in Arcade Battle or consolation money (much smaller) if you lost. All of this in-game currency directed players to personalizing characters.

From a gameplay perspective, most characters became faster because the game was back to the speed fans had been previously accustomed to. Newer characters like Feng Wei, Asuka Devil Jin, and Raven benefited a lot from this, but the returning roster had clever defensive/counter moves that carried over from the last entry.

The most important part of the legacy of Tekken 5 is Dark Resurrection, an updated version of the game released for PlayStation Portable and PlayStation 3. Dark Resurrection added new game modes, expanded online play, and introduced new characters: Lili, Dragunov, and Armor King II (yes I know, another off screen character death; this is his brother). The online play is the biggest game changer in this release, since it took Tekken global via Wi-Fi. People forget that console online gaming was limited to LAN play or ethernet cables prior to the PS3/Xbox 360/Wii era. Giving people the option to play without either of those hardwire options got a lot more people online, and Tekken has always been a great way to get people brawling online.

Next (Side)steps

Tekken 6, released first in 2007, was the most robust entry in the series when it came to new features. It included an Arcade Mode with prize boxes after each match and an unplayable boss character in NANCY-MI847J (who is still the only reason I don’t have a platinum trophy in this game). Similar to Tekken 5, there was an action mode with Scenario Campaign where you got to beat up enemies in a freeflow combat situation. The series even expanded to Xbox for the first time with an Xbox 360 version. Customization took its biggest leap here, allowing you to add special effects to characters when they attack, equip different kinds of accessories across the body, and personalize to your preference. Personally, I turned my Marshall Law into Kenshiro from Fist of the North Star. Sadly, this is the last entry with a full Story Mode for each character.

Combat wise, this entry is probably the most controversial. It’s here where the “rage” feature was added, allowing characters in their last vestiges of health to deal additional damage. On one hand, this really opened up opportunities for comebacks in one sided matches with carefully timed moves. On the other hand, it was a terrible thing to be on the receiving end of, especially in a close match where damage output separated you or your opponent from barely entering the rage state. “Bound” was the other gameplay dynamic added in this entry, which furthered combo juggles when an opponent flopped, opening them to more attacks.

The Next Episode

Tekken 7 is the modern entry I have spent the least time playing. Let’s start with the highlights: “rage” was expanded into “rage arts,” adding an ultimate attack feature equivalent into the game. This was expanded into “rage drive,” which would also be replaced in the next entry. There were a lot of other gameplay elements added as well related to movement, as “bound” became “screw,” which would later become “tornado” in the eighth release.

Meanwhile, Akuma from Street Fighter snuck into the storyline with some weird crossover universe storytelling. Bear in mind, this is a game where you get some interesting new DLC characters in LeRoy and Fahkumram, the return of Kunimitsu, and then nonsensical DLC add ins with Negan (The Walking Dead), Noctis (Final Fantasy 15), and then a brand new character, the vampire Eliza.

Unfortunately, this is the most empty game of the series. No arcade mode, no team battle, no new action mode, and offline features in general were lacking as well. This game solely existed for competition purposes, and honestly that’s okay. I’m old enough to admit when I’m not the audience for a game.

Reflecting on 30 Years

2024 kicked off with the release of Tekken 8, and as of the time of writing, the game sits at a score of 90 on Metacritic. If scores don’t matter to you, then perhaps its feat of selling 1 million copies on launch and over 2 million in a month might impress you. Personally, though, it’s the most fun I’ve had in a Tekken game in a very long time.

Tekken 8 offers a unique tutorial mode called Arcade Quest, where players are taken through the story of a fictional protagonist’s quest (it’s you, you’re the hero) to become the greatest player in the world. To battle online, you head to the Tekken Fight Lounge, which is a central hub like PlayStation Home (RIP). As you run around with your custom avatar, you can challenge people around you or use the match finding tool for ranked or unranked battles. Recent updates allow you to enter practice mode with your friends, and of course, you’re free to just vibe in the lobby.

While the online experience is the focal point, offline experiences do exist. The story mode is superb and concludes (for now) the tale of Jin versus Kazuya. Super ghost Battle lets you fight simulated versions of a real player’s approach with a character. These “ghosts” update based on their battle stats, and include staff who worked on the game along with real players’ data. You can even battle your own ghost which will develop as you fight more matches. The Arcade mode is about as interesting as Tekken 7’s implementation—you fight four battles and then you’re watching an ending movie.

Most importantly, the combat of Tekken 8 is the best the series has offered in a long time. The developers did a superb job taking the previous entries’ changes and boiling them down into a new synchronous system, and I’ve loved every minute of it.

In particular, practice mode in Tekken 8 is the most robust offline mode available. You can practice the new combo system, counters against opponents, and hone the fundamentals of the game at a level almost as good as a live opponent. It’s clear this is the definitive experience to practice competition situations and create every “what if” scenario. Between this and Super Ghost Battle, you’ll be ready for any tournament you could enter or any ranked online matches.

We can expect Tekken 8 to be supported for a long time, given we’re currently in the era of ongoing updates and balancing to keep competitive games fair. To the chagrin of many (including me), a cash shop was added along with a battle pass, meaning your favorite vintage uniforms are locked behind in-game virtual currency.

On a different note, and to everyone’s surprise, they brought back Heihachi Mishima from the dead. He’s the third of four Tekken 8 Season 1 pass characters, despite years of insistence he was gone for good. A free story explanation with playable sections of the first two released characters, Eddy and Lydia, explain how the Mishima patriarch is still a tyrant. Despite my skepticism, I was surprised to feel how great Heihachi feels in this return. The old man has still got it and is arguably my favorite version.

Recently, discrepancies were apparent in how his new stage and character were both listed as paid add-ons. The previous release for the second character, Lydia, included her stage for free. The situation was ultimately resolved, however, with players who logged in from late October until November 26 receiving a $5 credit.

This is where the active role of its executive producer Katsuhiro Harada and his engagement with the community is vital. He champions the series, staying involved with the community which is spread across Reddit, YouTube, and the various fan sites. You can often scroll through his tweets to get an accurate depiction of what’s going on, read his interviews, or watch his YouTube channel.

He even went as far as taking ownership over the recent misunderstanding and promising to oversee future business related releases. Harada’s relationship with the community—and vice versa—remains a unique dynamic, especially given how vocally online he continues to be. In an era where leadership often feels particularly separated from its gaming community, Harada embraces the players, and is all the more loved for it.

Continuing the trend of terrible DLC options, though, Clive Rosfield from Final Fantasy XVI joined the roster as announced at The Game Awards earlier this month. To say I’m dismissive of this addition is an understatement. Bring back vampire Eliza or Geese Howard, at least they made the cast interesting! Frankly, even adding Tifa Lockheart, a much more beloved Final Fantasy character, would be a stretch, though fans still clamor for her. I would settle, however, for a Josie return, or even Armor King (the man just looks so cool).

At the same time, I still dream for the day infinite ghost mode enters the menu or team battle will return. Unfortunately, like most free updates after launch, it will depend on “high demand.” What’s certain is that there’s still lots of time for fans to be playing Tekken 8 and lots of more controversial guest DLC characters incoming (not confirmed but looking at the past).

Fighting Forever

I turn 30 next month, so it’s good to see one of my longest purchased series is older than me. I got into Tekken when I was eight years old thanks to my brother’s insistence I make it one of my Buy Two, Get One Free on used games at GameStop. I’m glad I did, because even 21 years later, the best fights have yet to come, and I’m still looking forward to them.

Vaughn Hunt is writer who has loved video games since he picked up a controller. His parents wouldn't let him buy swords as a child (he wanted the real ones) so he started writing, reading, and playing video games about them. A historian at heart, you'll often find him deep into a rabbit hole of culture, comics, or music.