The (Horrifying) Sound of Silence

I’ve always felt that games are at their most emotionally effective not during key narrative beats or during intense conversations, but when the story is felt through atmosphere, art direction, and gameplay. Devolver Digital’s Carrion is the latest in a long line of games that present a compelling, thrilling story not with any words, but through sound, mechanics, and art direction. What separates it from other wordless games (like Inside or Journey), though, is how it embraces (and later subverts) power fantasy tropes, yet still manages to make the experience feel profound and affecting.

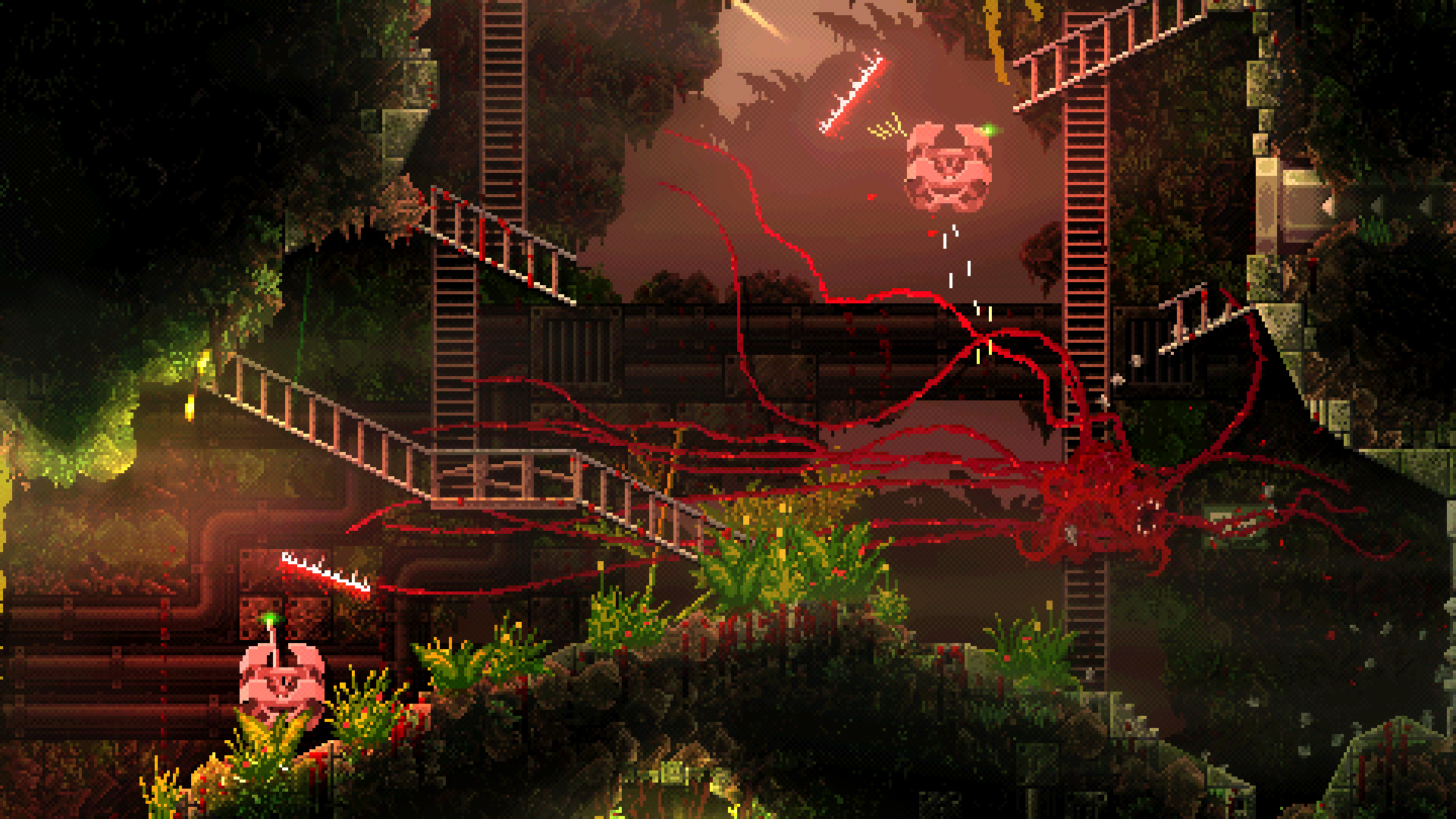

In Carrion, the player takes on the role of a toothy, slimy, tentacled mutant mass that must escape from a large, labyrinthine research laboratory environment by any means necessary. As a “reverse horror” game, Carrion tasks the player with using the gargantuan, amorphous red blob of death to wreak havoc, solve environmental puzzles, and conquer every nook and cranny of this dark and rusty lab by spreading its mass wherever you go. As you progress through various rooms and corridors of screaming scientists and armed guards, the horrific mass gains new abilities, allowing it to break open new gateways, cloak itself to avoid enemies, and even take control of a human by lunging a tentacle into their body.

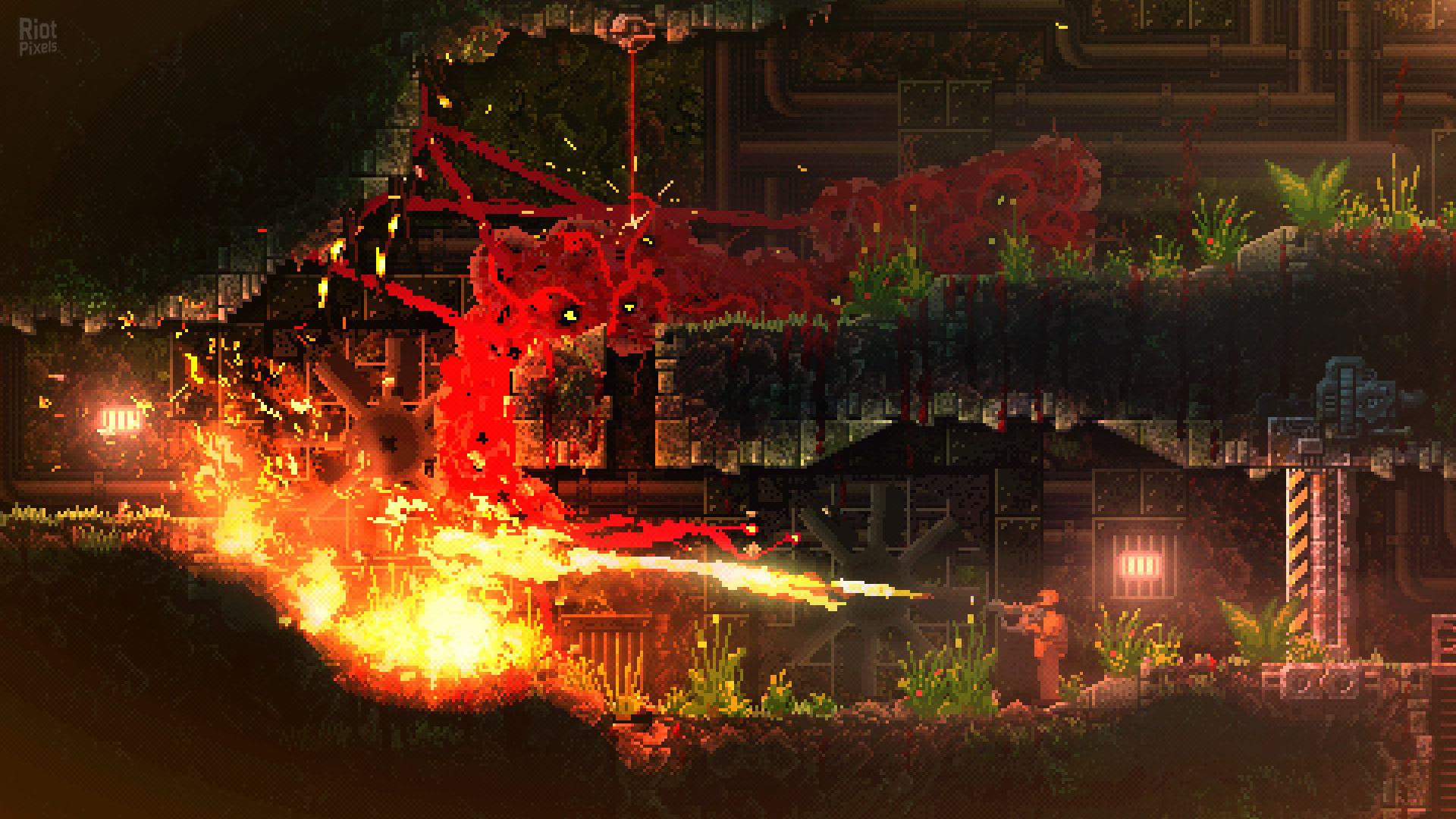

While the game has an actual plot that informs every decision the player makes (which I won’t spoil here), the true story is felt through everything else: the gnashing of human flesh; the clanging sound of a door getting torn off; the gasps and screams of humans knowing their bloody death is imminent; the loud roars of the monster itself (which the player can control at any time, much like honking in Untitled Goose Game); the quick and slick movement of the monster through spaces big and small; the dark, ominous soundtrack; the dimly lit passageways; and how the non-linear design of the world adds the right level of openness and variety to the experience.

Embrace the Darkness

Carrion may seem like a fairly straightforward horror-like experience, and in many ways it is. What makes it stand out, however, isn’t how much it relies on genre staples like darkness, gore, and screams, but how much it actually allows the player to control what kind of monster they want to be. Visually, the bloody creature looks the same no matter how you play it, but the player can go about most situations in any way they like.

Often, Carrion will present a room with several points of entry, allowing the player to decide if they want to surprise any guards from high or low vantage points. In addition, most rooms have a particular objective, such as hitting a switch, or interacting with a save point. These actions typically open up another door or pathway, allowing you to progress through the story.

This means players have the freedom to decide not just how they want to take out any enemies, but whether they want to kill them at all. (In some cases, though, you can’t avoid the carnage.) The story may be linear, but there’s still enough wiggle room for interactivity, making each player’s experience unique.

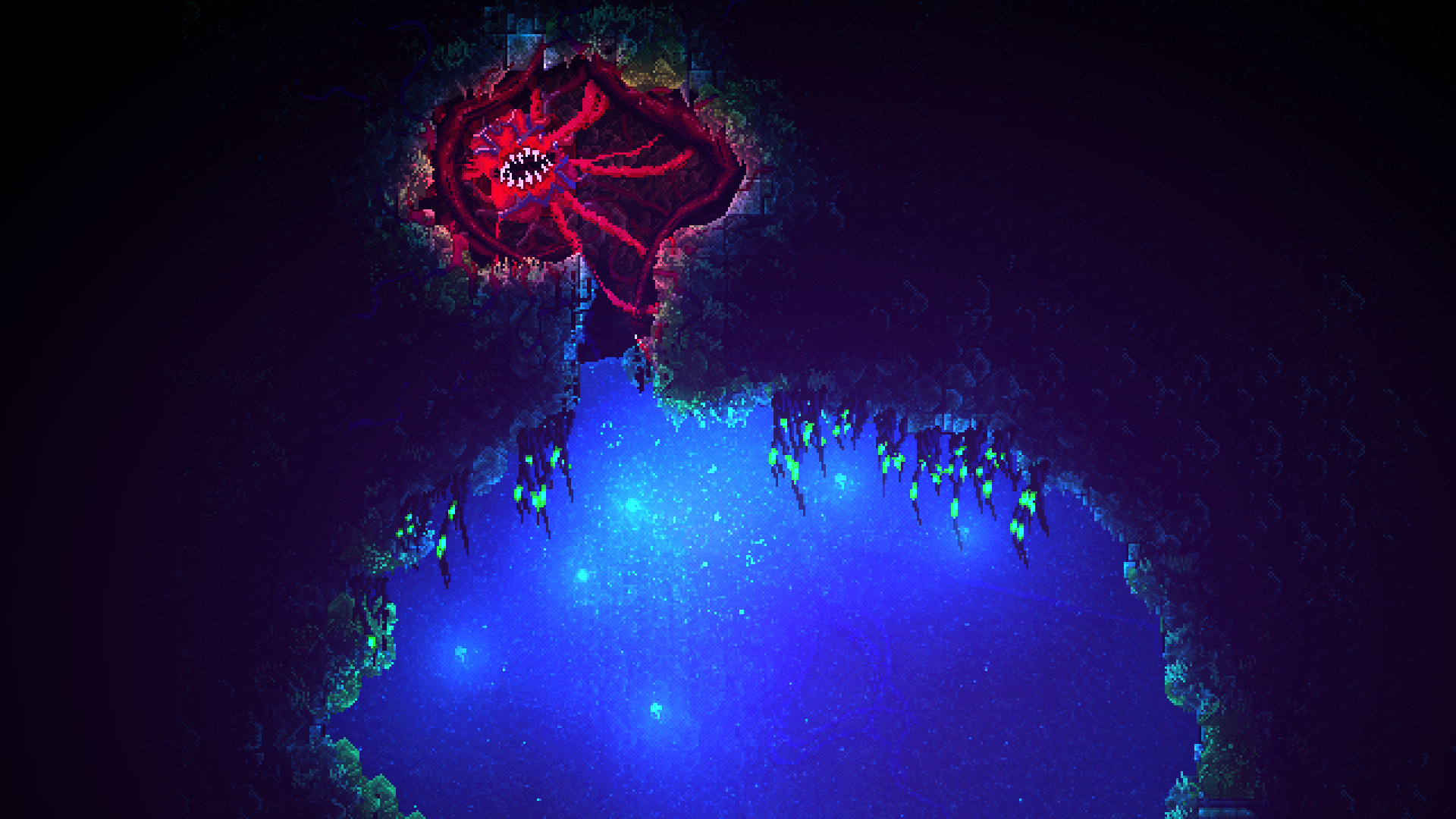

Moreover, one of my favorite aspects of Carrion is the aforementioned mechanic of finding save points to open doors. In each main area, you’ll find a set number of save points (usually four to six) that must all be unlocked to move on to the next area. Each save point is displayed as a hole from which the monster can spread its roots and establish a kind of home in the area, and the doors unlocked in the process are opened by the monster’s tentacles growing and rooting themselves into the doors.

This presentation of progress highlights a kind of tension found in the video game power fantasy, where the player often “conquers” whatever world they inhabit in search of resources and secrets, even if that sort of conquest is not the main purpose of the story. Samus Aran, Nathan Drake, Simon Belmont, and Lara Croft typically have a main goal in mind, but the player can look around for hidden content, more ammo, or item upgrades, and often can do so without the world reflecting that plunder. In Carrion, the point is to inhabit every corner of the facility and show how the player has turned a once hostile environment into its very own habitat. The game doesn’t let you take, destroy, or kill without leaving reminders of such destruction everywhere.

Carrion didn’t speak to me in words, but it did through every roar and with every quick, gross leap from the terrible biomass. It told a story of destruction, failure, helplessness, and, ultimately, salvation. It created an atmosphere of oppression and claustrophobia, only to later make me feel like nothing could possibly get in my way. And, in the end, it had the courage to demonstrate what kind of wreckage the player leaves in their path. All of that came through without even one sentence of dialogue.

Sam has been playing video games since his earliest years and has been writing about them since 2016. He’s a big fan of Nintendo games and complaining about The Last of Us Part II. You either agree wholeheartedly with his opinions or despise them. There is no in between. A lifelong New Yorker, Sam views gaming as far more than a silly little pastime, and hopes though critical analysis and in-depth reviews to better understand the medium's artistic merit. Twitter: @sam_martinelli.

i <3 carrion