The moment “Last Time (I Seen the Sun)” came on at the end of 2025’s smash hit Sinners, I was captivated and didn’t dare leave the theater. My first thought was that this was Sinners’ version of the ladder scene from Metal Gear Solid 3: Snake Eater. It was a perfect, unexpected end-cap to a movie where music drove much of the film, guiding us through scenes, foreshadowing events or character’s emotions, and mesmerizing its audience.

The harmonies from the duet of Alice Smith and Miles Caton combine elements of blues, rock, country, soul, and spirituals. Despite the song only being three minutes and 19 seconds, it captures the film’s narrative, evoking the longing and regret the film paints in its two-hour-and-17-minute run time. What makes this song transcendent is an underscore of four sounds we hear repeated throughout the film.

Sound as a Motif

The Power of a Single Chord

The first sound is the high pitch chord we hear crescendo at the start of the song. It’s commonly placed within moments of reflection in the film as characters recall moments of beauty. The most memorable is Sammie’s, as he thinks about his ride with Stack, the sun high in the sky over their laughter and conversation as the wind whipped around them driving through the cotton fields. And, later, there’s Smoke’s, as he reminisces about how that day started off so well with his brother and all their family and friends.

The sound itself perfectly captures longing and reminiscence, as it represents memory and triggers reflection, perfect for the beginning of a song that recounts much of the film’s themes. There’s lots of discussion about high pitch frequencies being good for the body, but regardless of whether they are founded or unfounded, this sound is calming. It feels like you’re ascending through time as you think of a memory that is perfect, the sound of the guitar reminding you that you are still on this earthly plane.

Sammie’s Guitar

The next sound is the acoustic guitar played by Sammie, portrayed by Miles Caton as he showcases his talent with the blues. I don’t know if this was intentional, but the pitch of the guitar’s twang reminded me of the 1972 film Deliverance. While I’ve never seen it all the way through, its sound, and the film at large, had a lasting impression on American culture, but left a legacy of being anti-rural and anti-working class.

Intentional or not, the sound reminds us of an important juxtaposition and historical context we see portrayed in Sinners. Everyone thinks of Smoke and Stack as living successfully in Chicago, but the two of them speak of the city with disdain, as they faced the same racism and discrimination there as they did in the South. Historically, this struggle to adapt was true for many families, particularly during the first Great Migration, a period where Black Americans moved up north after World War I. These families brought with them their traditions from the South, which would later shape much of the North, as these same families traveled back and forth between the two locations. It’s why, from New Orleans to New York, you were guaranteed to find a jazz club throughout the middle of the 20th century.

Adding a layer to this story is the fact that Black veterans have served in every armed conflict since the American Revolution, but have never received the respect of fellow veterans or citizens on their return home. Even “the war to end all wars” couldn’t ease the mounting racial tensions, which were a bi-product of Reconstruction failing. To this point, massacres would take place in Elaine, Arkansas; Rosewood, Florida; and Tulsa, Oklahoma, with the former being among the first Supreme Court wins by the NAACP.

Families who made journeys north still faced racism and discrimination, similar to Smoke’s and Stack’s experiences, on top of class discrimination, as many were working class. In many ways, their decision to move back, while prompted by false premises of riches to be made, substantiates their preference for rural and working class folks because that is their community. This isn’t to say Smoke and Stack were doing revolutionary work, but they did wish to support a community of their own people to the best of their capabilities.

Foreboding Bass

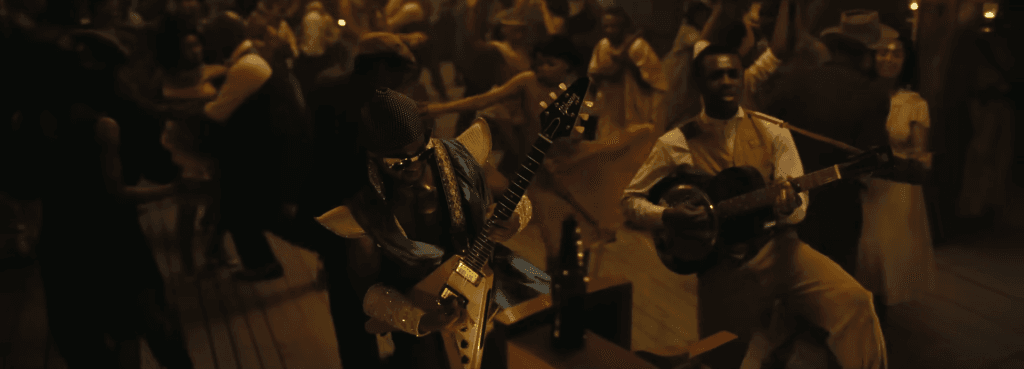

The downscale of four notes has never felt more foreboding than in Sinners. Each time this sound began, you knew something bad was about to happen. It’s probably the most noticeable of the four sounds we hear in “Last Time,” and it’s represented throughout the film. The last note is particularly noteworthy, as it echoes out alongside key mood changes in the film, the most outstanding being the transition to the “musicians” as they approach Club Juke.

Juke joints were the pre-eminent place to hear the blues. A staple for Black Americans during segregation, these settings were where you could relax after a long week of work. In the film, this was a safe haven for many of the characters in attendance, who by day were sharecroppers. While farm work was hard work, farming on land you didn’t own and giving up parts of your yield made it even harder, which is the definition of sharecropping. This cycle of bondage was a legacy of slavery and resulted in many families being caught in a cycle of poverty.

We see this play out in the film as “Club Juke,” the name given to the juke joint founded by the twins, lost money all night due to its customers attempting to pay with local plantation coins instead of dollars. These were a closed-circuit currency, which could be used to pay for necessities by sharecroppers, but were only good on those plantations and worthless elsewhere. This same system was later emulated by company towns, but I digress.

The Future: The Electric Guitar

Maybe it was inspired by Parliament-Funkadelic, or perhaps Jimi Hendrix or Ernie Isely, but that first chord of electric guitar we hear is undoubtedly the future of blues becoming rock. Its use in “Last Time” drives the song forward, coupling perfectly with the harmonies of Smith and Caton into a symphony of musical decadence carrying the weight of hope, longing, and sorrow.

Iconically, we see this guitar appear in the film as Sammie calls forth the ancestors of present and future. The musician playing it is dressed in an outfit that looks like the stage decor of the lead guitarist of an Earth, Wind, and Fire concert, but that makes him all the more intriguing. The electric guitar is unmistakable from its acoustic counterpart, but is just as controversial in the hands of the artist. Jimi Hendrix’s rendition of the national anthem remains one of the most controversial performances of its day, and only in recent decades has it become widespread news that Black artists made rock ‘n’ roll what it is.

What’s still ongoing, nevertheless, is the public unearthing and decoupling of how much was stolen in the early days. The next time you listen to “Hounddog,” skip Elvis and listen to the earthy richness of Big Mama Thornton’s original.

The Power of Black Music

The Juke Joint

One of the last juke joints in America was Gip’s Place, located in Bessemer, Alabama. For first timers, it felt a little daunting to find, as Alabama has the least well-lit streets of any place you’ll visit. (At least the state is straightforward to navigate — just beware drivers who run red lights.)

It was clear you’d arrived in the right place when you saw the following: a first-come, first-serve grass parking lot, a makeshift “box office,” which was a cash-only solo operation, and a backyard full of outside wonders aging in the rust of outside exposure. Walking down a dedicated path, you’d pass food and hot chocolate before reaching the small stage, which was roughly the size of your smallest local music venue and an intimate seating area to match. And most importantly, in the front, you’d find a small dance floor, which doubled as a footpath throughout the entire place.

As someone who lived in Birmingham, Alabama, getting myself to this palace of the blues was a simple 15- to 20-minute drive, which culminated in crossing railroad tracks and turning down the small streets of a close-knit neighborhood. Often, I went because one of my friends found it the most magical place in the “Magic City.”

Unsurprisingly, the reasons people go to a juke joint, or, in today’s case, a concert, haven’t changed: It’s all for the music. For just a few hours, the worries of your life fade away and you can come together with your community to appreciate the artistry on display.

In its simplest form, community-gathering was why the juke joint existed, but since this is America, it came with the added weight of racism, which in turn led to innovation. African Americans were banned from bars and similar public social spaces for whites. Yet, by comparison, this was surprisingly freeing because, during slavery, enslaved people were banned from religions that weren’t Christianity, banned from using drums (since slave masters feared the power of these instruments in ritual), and banned from gathering at large save for the aforementioned religious purposes led by their enslavers.

So, they built their own space, where they honored their talented musicians and brought together their community. These spaces were sacred in the safety they accomplished, rivaled only by churches arguably. They gave rise to the Chitlin Circuits of the 20th century and were a hallmark of the community until music was heavily commercialized, feeding artists and helping them survive when they otherwise would have struggled.

The Soul of the Art

The most profitable export of the U.S. is Black creativity. Be it the blues, jazz, rock, or hip-hop, these creations all have enriched the world but have only sparsely enriched the communities that created them. Many feel the consciousness of music has faded in its attempt to uplift communities and speak about issues that matter. The music business is the most damning situational shift in this discussion, along with how the industry has treated artists, whether commodifying their sound or putting them out to pasture.

The most profitable export of the U.S. is Black creativity.

Sinners released in a year when our political environment was disastrous, AI slop entered every creative space, and people struggled to afford daily necessities. To top it off, we lost D’Angelo, one of the most intentional, studious, and electrifying artists, and someone who echoed an era of musicianship and craft comparable to James Brown, Michael Jackson, and the greats of the stage.

Yet the end is not nigh. In August 2025, Jon Batiste put out the spectacular album Big Mooney, driven by blues, soul, and a blend of genres we hear in Sinners. His discography alone demonstrates his dedication to his craft, his love of who he is, and his commitment to the issues he holds dear.

Alice Smith, a stellar performer whose soul and artistry brim through each breath of her vocals, also lent her vocals to “Last Time (I Seen the Sun).” Outside of her being featured on the Sinners soundtrack, her performance of “I Put A Spell On You” was exemplary, and I am ecstatic to experience her sound as a new listener moving forward.

Likewise, Miles Caton emerged globally as a superb talent through his award-worthy performance as Sammie. His voice evokes the soul and memory of the griots and firekeepers we hear mentioned at the beginning of the film, as if from another era. Regardless of what music he puts out next, I’ll be following.

Excellence at Work

There are so many more artists I could mention here, like Lianne La Havas, who is one of my all-time favorites, or the impeccable Jill Scott who constantly reinvents her music during live performances. Music in its best form is a personification of our experiences. How we write about them and how we express them all contribute to the art. Although pain has defined much of the African diaspora in this country, it is not the definitive way we live our lives. Just look at an elderly Sammie, portrayed by living blues legend Buddy Guy. After much turmoil, he found a complete life, overcoming the trauma imposed upon him.

Music is a great tool for healing. It moves us emotionally, allows us the space to process our world artistically, and continually inspires us. Amid strife, African Americans have always found purpose, built creatively, and chosen love and compassion as their compass. “Jump on the work before it jumps on you” is what Sammie’s father used to tell him in the film, and no one puts in the work quite like us.

Vaughn Hunt is writer who has loved video games since he picked up a controller. His parents wouldn't let him buy swords as a child (he wanted the real ones) so he started writing, reading, and playing video games about them. A historian at heart, you'll often find him deep into a rabbit hole of culture, comics, or music.