Putting Old Classics Under the Modern Microscope

Though video gaming as a medium is still relatively nascent, enough time has passed since the original Pong that we as gamers have begun to set aside many of the icons of the past in favor of more modern experiences. Some older treasures, such as the oft-praised Sega Saturn RPG Panzer Dragoon Saga, are simply hard to find. Others, such as many of the popular first-person shooters from the 1990s like Perfect Dark and Turok, have become obsolete in the face of rapid technical advancements.

But what do we make of the older games that are easy to play and haven’t been entirely phased out of gaming colloquy? Certain genres, such as turn-based RPGs, sidescrollers, and point-and-click adventures, have only improved marginally over the years. Does that mean Donkey Kong Country feels the same to play as Celeste? What role does nostalgia play in how we view these games? Is it essential for gamers to consider the historical context of each classic game’s release, or simply review the game in a vacuum?

As playing video games becomes a more legitimate pastime, it behooves us to examine how we talk about games that are decades old, particularly when it comes to the language that we use. The common description for a game that still plays well years after its release is that it “holds up.” What standard, exactly, does it “hold up” to? In order to conclude what exactly that means, I started playing some older games to determine whether or not I believe they hold up. The games I chose to discuss fall into the following criteria:

-Must be from a genre that still effectively exists in some modern form (i.e. not particularly interested in going back and playing Pong or Dig Dug)

-Must be at least 15 years old

I also chose the following games for this piece because either A) I played or replayed them fairly recently or B) I felt that they, at one point, were considered the pinnacle (and future) of games. Through this exercise, I aim to figure out why certain games hold up over time and why some don’t.

Star Fox (SNES, 1993)

The first ever game to use the Super X graphics acceleration coprocessor powered GSU-1 (basically, a chip that made legitimate 3D graphics work on a 16-bit system), Star Fox was truly a marvel of the early 1990s, presenting an action-packed sequence of spaceship battles that are equal parts exhilarating as they are seizure-inducing. That said, if you were to view the original Star Fox for the first time in 2018, you’d judge it the same way you judge a rotary telephone or a cassette player. The Super Nintendo space shooter served its purpose in a different era, but now is a fossil.

I’ve been familiar with the visual presentation and music of the original Star Fox for years, but I never actually had the chance to play until a few months ago. Star Fox 64, the clearly superior re-imagining of the SNES game, was a staple of every 90s gamer’s childhood, so I figured it would just feel like a more primitive version of that experience. In many ways it is, but in the same way that Lou Ferrigno’s depiction of the Incredible Hulk is a more primitive version of the Hulk in the recent Avengers films: just because the subject matter and core concepts are the same doesn’t mean that both works are even remotely similar in quality.

I actually rather enjoyed the experience, despite the slow-as-molasses frame rate and the fact that all the enemies look more like random collections of shapes than actual robots or spaceships. The controls work just fine, and the game presents some interesting challenges and level design. Still, I wonder if I would have enjoyed this game if it didn’t have the Nintendo seal of approval or the same name as one of the best games of the N64-era. I wonder how I’d feel about it if it came out yesterday instead of fifteen years ago. I wonder if, had it not been among the games on the SNES Classic Edition, I would have ever played it at all.

Star Fox was a much more fun game than I expected, but its flaws are too obvious and damaging to ignore. Even when you consider that its ugly graphics and user interface were revolutionary for their time, its presentation simply muddies everything, as I can barely tell what’s going on some of the time. This is particularly troubling when you compare, say, Super Metroid to modern games in the same genre and see that its presentation holds up just fine. Most of the game’s sound design is too busy, with the sound of the arwings clashing with the sounds of dozens of explosions, crashes, and Slippy crying for help. Basically, Star Fox tried to do a lot of things that were simply done much better on later consoles. The actual gameplay of Star Fox holds up well enough, but pretty much nothing else does.

Verdict: No, but holds up slightly better than I expected.

Grand Theft Auto: Vice City (PS2, 2002)

When I think Rockstar Games, I immediately think of polish, fluid controls, great writing and voice acting, and beautiful, sprawling open worlds. From Grand Theft Auto III all the way to GTA V, Rockstar’s work has always displayed the best that open-world action games have to offer. Well… at least I felt that way until I went back and replayed Grand Theft Auto: Vice City, a game I viewed for the longest time as earth-shatteringly innovative.

Vice City was one of the first games that truly blew me away when I first played it as a pre-teen. The city seemed endless, and few other games gave me the same level of freedom. You could drive any car, carry an abundance of weapons (including a katana), fly helicopters, cause a rampage, visit a strip club, pick up sex workers, and incite gang battles, all in a day’s work. As a naïve 12-year-old playing at a friend’s house (my parents didn’t let me play games like this at home), I felt like we had reached the pinnacle of game design.

Playing it now, the gunplay feels prehistoric, the world is remarkably small compared to its modern-day counterparts, and most of the game’s extracurricular activities just seem like filler. Many of Vice City’s missions remain exhilarating and full of flare, but most of the side missions and optional content have aged poorly, with wonky controls and bad voice acting.

Additionally, GTA: Vice City is simply too problematic to be as well-received today as it was a decade and a half ago. Sure, every GTA game lets the player kill innocent people, solicit prostitutes, and steal everything in sight. But unlike its successors, Vice City doesn’t really let you do much else; if you want to do something that isn’t murdering drug kingpins or stealing motorcycles, you’re out of luck. In Grand Theft Auto V, you can spend your time skydiving, playing tennis, deep-sea diving, or even running a taxi service (my personal favorite) instead of wreaking havoc left and right. Vice City only allows players to act like monsters, and that’s not even mentioning the obvious racist caricatures and vicious stereotyping of women and people of color.

I still like many parts of Vice City. The pastel colors and clear Miami Vice references lighten what would otherwise be a somber experience, and I hope Rockstar revisits some of the best of Vice City into the inevitable next iteration of GTA. But if you have no nostalgia attached to this PS2-era game, you might as well just skip it.

Verdict: Some of it does, most of it doesn’t.

Super Mario RPG: Legend of the Seven Stars (SNES, 1996)

The mechanics of traditional turn-based JRPGs haven’t really changed all that dramatically over the years, as modern releases like Bravely Default and Project Octopath Traveler are really just more polished versions of their ancestors. Still, it’s worth it to examine older RPGs that pushed boundaries for their own time, and if such attempts at innovation were a harbinger of the future of game development or a complete miss.

One such game is Super Mario RPG: Legend of the Seven Stars, a colorful and bizarre RPG that Nintendo made in collaboration with Square for the SNES. The first attempt at telling a broader story in the Mushroom Kingdom, Mario RPG mixes basic turn-based, team-oriented battle functions with the platforming and timed button-mashing that has defined the Mario franchise. For example, if you select a jump attack with the mustachioed plumber, you have the option of timing each jump on your enemy’s head in order to increase damage done.

Since the gameplay of older turn-based RPGs isn’t radically different from more recent games, generally they hold up just fine. Super Mario RPG is no exception, and the additional mechanics (e.g. isometric platforming, timed attacks, button-mashing) actually make the game feel oddly fresh, even if its dated visuals and 90s-style soundtrack remind you of its age.

The best part of SMRPG? Unlike many of its modern equivalents (i.e. the Mario & Luigi franchise), it doesn’t do too much. The story moves along relatively smoothly and the player isn’t bogged down with scores of pointless side quests. The game relies on humor to add to an otherwise simplistic plot, but it never attempts to make the story seem bigger and more complex than it needs to be. The Super Nintendo has plenty of games that remain playable by today’s standards, and Super Mario RPG is certainly one of them.

Verdict: Yes.

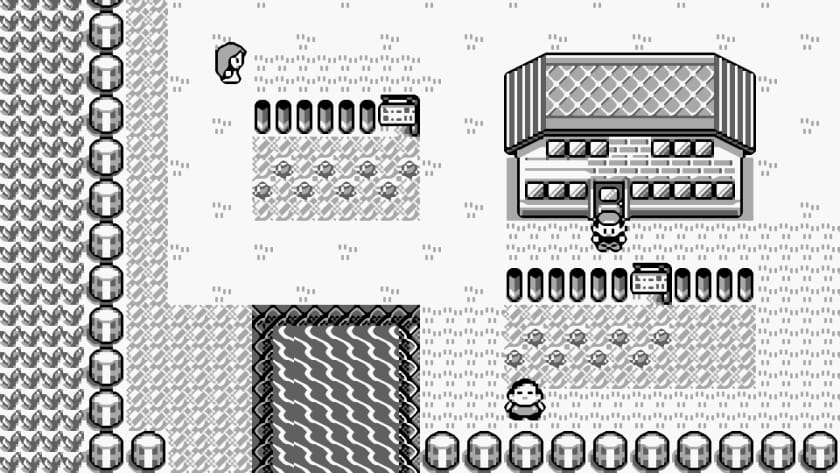

Pokémon Red/Blue (Game Boy, 1998)

Up until recently, I had thought the Pokémon series had basically remained the same since its initial release. After playing Pokémon Blue last summer in anticipation of Sun and Moon, I realized how mistaken I was.

The fundamentals of Red and Blue have existed throughout the entire series (except for Sun and Moon), but the series has made remarkable strides over the past two decades. The actual images of the little creatures were awkward and disturbing in the first entries, and since have been improved tremendously. The item management in Red and Blue was atrocious; all of your items were put in the same folder AND you had a hard item limit, making stocking up on fun finds a stressful and annoying affair (sure, you could store items in your PC, but that just seems silly given how much time in the game is spent traveling).

The battles are mostly the same as they are in modern iterations, but it’s impossible to know the effects of each attack, as the game provides very little in the way of explanation. When I first played Red when I was eight, I thought “Swords Dance” would be the most awesome attack in Charizard’s arsenal, only to be disappointed that I gave up on “Ember” (you know, a useful move) for something that makes me stronger I guess.

All that said, the open-endedness and focus on exploration and collecting (the story in Red and Blue hardly exists or matters) make the original games the purest Pokémon experiences out there. I still enjoy the quick, action-packed battles and the excitement of finally running into that Pikachu you’ve been hunting for hours. The pure joy of barely besting a gym leader remains one of the most exciting achievements in gaming (even if I’ve done it a million times) and the original Elite Four still presents an exciting challenge.

Verdict: Yes, but barely.

Summary

I could go on and on about games from my childhood and whether they still feel good to play, but the examples presented above should be enough of a sample to determine which things to look for when evaluating whether a game holds up over time. For the purposes of this exercise, I’ve divided such criteria into three groups: MUST HAVE, CAN’T HAVE, SHOULD HAVE.

Based on the four games listed earlier, here are the elements important to a game holding up:

MUST HAVE:

-Tight controls

-Good presentation

-Replay value

-The “Amnesia Factor,” i.e. if I suddenly had amnesia and don’t remember playing the game back in the day, would I enjoy playing it now?

Next, here are signs that a game does not hold up:

CAN’T HAVE:

-Problematic themes/motifs

-Janky graphics/frame rate

-The “Doing Too Much Factor,” i.e. does this game try (and fail) to be a more advanced game than was possible at its release?

Finally, things that would certainly help a game hold up but are not entirely necessary:

SHOULD HAVE:

-Streamlined user interface

-Just the right amount of explanation/exposition

-Something that makes it unique (for its time)

These criteria might not be perfect, but at least they’re a start.

Sam has been playing video games since his earliest years and has been writing about them since 2016. He’s a big fan of Nintendo games and complaining about The Last of Us Part II. You either agree wholeheartedly with his opinions or despise them. There is no in between.

A lifelong New Yorker, Sam views gaming as far more than a silly little pastime, and hopes though critical analysis and in-depth reviews to better understand the medium's artistic merit.

Twitter: @sam_martinelli.