Rethinking the Language Around Video Games

In a Punished Notes from last year, I decried the overuse of gaming terms like “metroidvania,” as often such words and phrases do little to actually describe the experience any game presents. While I understand why someone might lean on a certain vernacular when describing various works (and I am certainly guilty of saying all the following terms more frequently than I should), the time has come for us to rethink how we talk about games in order to describe them in a more accurate manner. I’m not calling for the obliteration of such terms, either; I just believe we should know what we’re saying when utilizing these words.

The following are five particularly notable examples.

“Metroidvania”

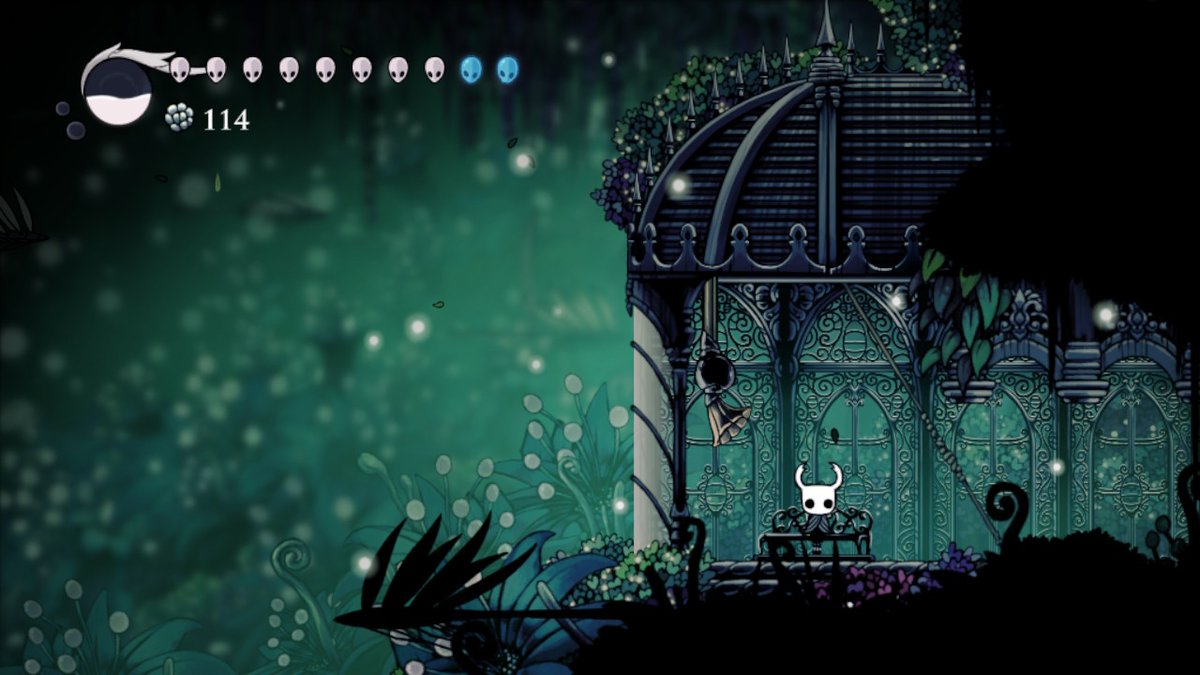

The inspiration of this very article. People often use the portmanteau of Metroid and Castlevania to describe an action-based game with a linear story but a non-linear progression. Ori and the Blind Forest, for example, largely exemplifies this moniker, as there is a clearly correct way to beat its main story, though the game still has backtracking, item progression, and secrets hiding in plain sight. Meanwhile, Hollow Knight, lauded by many as a “metroidvania,” shares very little in common with any Metroid or Castlevania game, as the only common system among all those franchises is non-linear platforming. Hollow Knight doesn’t have a single ending, and even if it did (the so-called “true” ending, for example), the game’s overworld is largely open, with “main game” tasks that can be completed in any order. If anything, Hollow Knight shares more in common with the original Legend of Zelda than Metroid; you travel through Hallownest searching for items and power-ups that open up different parts of each area, and you can progress through the game in whatever manner you like.

Team Cherry’s indie hit might just be one example of the fallacious nature of the term, but critics and fans alike frequently throw out “metroidvania” to describe just about any non-RPG with some form of non-linear progression. Obviously, “metroidvania” might be easier to understand than “non-RPG with some form of non-linear progression,” but we should really save it for games that better identify what made, for example, Super Metroid so popular in the first place. How about this: Instead of calling every game like Hollow Knight a metroidvania, how about just calling it a non-linear 2D action platformer? That might sound like word soup, but I swear that makes sense if you actually played the game.

So why did people call Hollow Knight a metroidvania? Honestly, its 2D presentation probably has more to do with that than anything. The game looks in some ways like Metroid or Castlevania, so some may naturally make that connection. Still, if you need to use a hokey phrase, the more accurate way to describe Hollow Knight would be “2D Dark Souls,” as the way the player progresses through the game and learns from trial-and-error shares a lot with FromSoftware’s most famous IP. On that note…

“The Dark Souls of…” or “Soulslike”

While two terms are listed here, they both stem from the same phenomenon: A lot of video games have clearly taken inspiration from the Dark Souls series, so any game with similar concepts or gameplay immediately gets compared to the franchise. That said, these terms are not used to describe the same thing. Saying a game is “like Dark Souls but…” really just means that it’s a more painfully difficult version of what is largely a different genre. It’s how people talk about games like Code Vein (“anime Dark Souls”) or Remnant: From the Ashes (“the Dark Souls of shooters”).

Honestly, I don’t have a huge problem with this way of speaking, as gamers typically know what you mean when you say it. However, it kind of sells Dark Souls short. I have my qualms with the series (and FromSoft as a studio in general) but the games are interesting and complex for reasons beyond their insane difficulty. If people just liked Dark Souls because it was hard, there’s no way it would be arguably the most influential single player game of the decade. Honestly, just calling a game “hard” is enough (though getting more specific about how it challenges the player is probably better).

When it comes to calling something a “Soulslike,” it’s kind of the same deal as “metroidvania”: If the game actually has a lot in common with Souls, like the drip-feed of lore and use of “souls” or something like it as a currency, then it’s an accurate term. If it’s just a non-linear 3D game with tough enemies, then call it that, since Dark Souls didn’t invent that genre. The more we talk about games like they’re just copies of each other, the less we actually see what makes them unique.

“Open World”

What exactly does it mean for a video game world to be “open”? Does it imply that you can access any point on the map at any time? Does it mean that the world is especially big? Does an “open” world have places that don’t serve any story or gameplay purposes? Does “open” have to indicate non-linearity? If a game is linear but has accessible side quests and side areas along the way, does that count as an “open” world?

“Open world” as a term perturbs me mainly because we don’t have a consensus answer to any of these questions. People tend to have their opinions on which games have good or bad open worlds, but we often find ourselves talking about such worlds in ways that fail to adequately describe what traversing through a certain game world entails. For example, The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild clearly fits the “I know it when I see it” criterion for open world games, but so do older (and smaller) titles in the series like Link’s Awakening. Still, that didn’t stop uninformed Reddit commenters and even some critics from praising Breath of the Wild’s world to a point of calling it the first “true” open world Zelda.

Why? Well, Breath of the Wild’s world is astronomically larger than that of any prior Zelda title, and everything in it can be done in any order the player likes. That might mean the game’s world is a better open world than that of Link’s Awakening, but the latter title also features a fully traversable environment with a variety of tasks that can be completed in any order the player wishes (not to mention a collection of side quests and challenges one would only discover through wanderlust). Just about every Zelda game utilizes open world mechanics, so the idea that Breath of the Wild finally realized a “true” open world is nonsense.

The confusion doesn’t end there. Chrono Trigger’s world involves backtracking, rewards for wandering, and the ability to complete a set of side quests in any order, yet few would say that game has an “open” world. Rise of the Tomb Raider, on the other hand, is described by many (including people on this very site) as “open world,” even if there’s little incentive to go back and explore once the main story is finished (or really at any time throughout the adventure, as the story is 100% linear). A large portion of Gears 5 features environments that one might describe as “open world,” but the player can’t traverse through different locales between acts in the game at any time they want, and any of the side content one might find while exploring the world is entirely optional and has little impact on the game’s story or progression. Basically, all of these games have some kind of open world, but that term means something completely different in each of those cases.

Generally, I know what people mean when they talk about a game’s open world, but we need to go a step further when using that term. The vast province of Skyrim opens up to the player immediately, while all the pieces of Ocarina of Time’s world have to be unlocked by progressing through the main story. The language we use when discussing these games should reflect that key difference.

“Immersive”

Ah, the old “immersive,” or as some people view it, “when a game does cool realistic-ish things I like.” Maybe hyper-authentic graphics create immersion. Maybe forcing a player to drink a potion or eat food without pausing creates immersion. Perhaps having a stamina system is immersive, as is the lack of a mini-map. In some cases, one might say that even the ability to pause a game, select a health item, and use it mid-combat breaks immersion, as it presents a completely unrealistic solution to… I guess… a “realistic” matter?

The main issue I have with the way people throw “immersive” and “immersion” around is that they often apply such terms to mechanics and systems and not to style choices, art direction, sound design, or even user interface. For example, Red Dead Redemption 2 was largely hailed as a groundbreaking work in terms of immersive qualities because the main character gets skinny when he doesn’t eat, the horses wander around if not tied to a post, and because uncleaned guns tend to fire more erratically. None of those mechanics, however, actually made the game interesting or immersive; if anything, they unnecessarily gamified otherwise mundane tasks, meaning the player was always thinking about basic movements and actions in ways contrary to how an actual human might. If anything, any immersion found in Red Dead Redemption 2 would come from the brilliant artificial intelligence, character interactions, town and city architecture, and other qualities that have little (if anything) to do with actual gameplay mechanics. Sure, certain mechanics and systems can be immersive, but achieving the oh-so-godly level of immersion so many seek requires better world-building, in terms of both writing and aesthetics.

My qualms don’t stop there, as another big problem I have with the term is that it is often used as though it were an objectively positive quality for a game, and that’s not always the case. Sure, Deus Ex, Prey, and tons of open-world RPGs aim to create immersive worlds that feel real, but so many other games have no interest in presenting anything like that. Nothing about Super Mario World feels realistic, because why would it? Should I be concerned about the lack of immersive mechanics in Tetris or Elite Beat Agents? Is Pokémon Yellow a lesser game fundamentally than Mass Effect because Pikachu can only say their own name? We can’t just keep tossing out a term like “immersive” as though it reflects some kind of undeniable truth about a game.

I’m not sure there’s a valuable substitute, but I hope gamers understand that “immersive” is a meaningless term if it’s viewed as quintessential and particularly mechanics-focused, and that any resistance to such “immersive” qualities is fundamentally negative. You can still use the word in the proper context, but just be more thoughtful about it, okay?

“Value”

You see it in the comments section of any review of a short game with no multiplayer. “Seems cool, I’ll wait until it’s on sale.” “$60 for a ten hour game? Doesn’t seem like good value.” “Oh, Skyrim is on sale? That’s a steal for a 100+ hour experience!” Apparently, in addition to providing critical takes on games, reviewers are expected to talk about a title’s “value,” as though they were appraising jewelry or antiques.

I understand why people think this way. Money and time are limited (and increasingly valuable) resources, so it makes sense that someone would prefer to spend both wisely. If you’re someone who only purchases two or three new games every year, it might matter to you that the Link’s Awakening remake isn’t any longer than the original Game Boy version, but costs a full $60. Maybe you’d prefer to wait until the price drops (which it never does for Nintendo games) or buy something you know you’ll be playing for several months, like Overwatch or Assassin’s Creed Odyssey. It’s not my place to tell people how and where to spend their hard-earned dollars, and I, too, tend to wait for better prices.

Still, I want to push back against the notion that a game’s “value” is tied inherently to how many hours of gameplay it provides. I paid about the same amount of money for Assassin’s Creed Origins, a game I played for 40+ hours, as I did for Inside, which I beat in under four hours, and I would take Inside over Origins every single time, even if Origins were somehow cheaper. Skyrim provided me with nearly three times the gameplay hours of Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus, but none of those Skyrim hours matched the incredible intensity of Wolfenstein’s eleven strong hours.

We don’t do this for anything else. Nobody would say that a ticket to see Once Upon a Time in Hollywood should cost more than a ticket to Booksmart because it’s a longer film. It’s unconscionable to think that an avid reader would wait until Between the World and Me goes on sale because they couldn’t justify paying full price for a short book. Why would we view a video game the same way? The way we view a game’s monetary value shouldn’t matter much at all, particularly when you consider the labor cost associated with making all games, big and small.

Again, I can sympathize with those who would rather wait for a price cut (or an inclusion on a service like Game Pass) before deciding to play a game they can beat in under a week. I just believe that doesn’t mean the game is inherently less valuable.

The way speak out on art changes with each generation, and as our understanding of video games improves over time, so do the words we use to describe them. Hopefully, we can learn to re-contextualize certain terms or avoid using dated language when discussing our favorite digital experiences. Until then, we should just take a minute before saying that the latest valuable metroidvania is the Dark Souls of immersive open world games.

Sam has been playing video games since his earliest years and has been writing about them since 2016. He’s a big fan of Nintendo games and complaining about The Last of Us Part II. You either agree wholeheartedly with his opinions or despise them. There is no in between.

A lifelong New Yorker, Sam views gaming as far more than a silly little pastime, and hopes though critical analysis and in-depth reviews to better understand the medium's artistic merit.

Twitter: @sam_martinelli.