Climbing the Mountain Within You

Minutes into my first playthrough of Celeste, I found myself breathing more heavily than usual. The 2D platformer certainly presented some light challenge early on, but that wasn’t what was causing such a physical sensation. It was the atmosphere, the daunting-yet-inspiring music, and the frequent reminders of how easy it was to fail that had me lightly panting and drawing strange looks on the commuter rail I take to work every day (I played this game on the Nintendo Switch). Luckily, the game didn’t mock me for my frequent deaths or make me feel inadequate or incompetent, as harder games like Dark Souls, Wolfenstein II, and Cuphead are wont to do. Instead, the game encouraged me to keep trying. The game actually believed in me.

A Journey to the Top

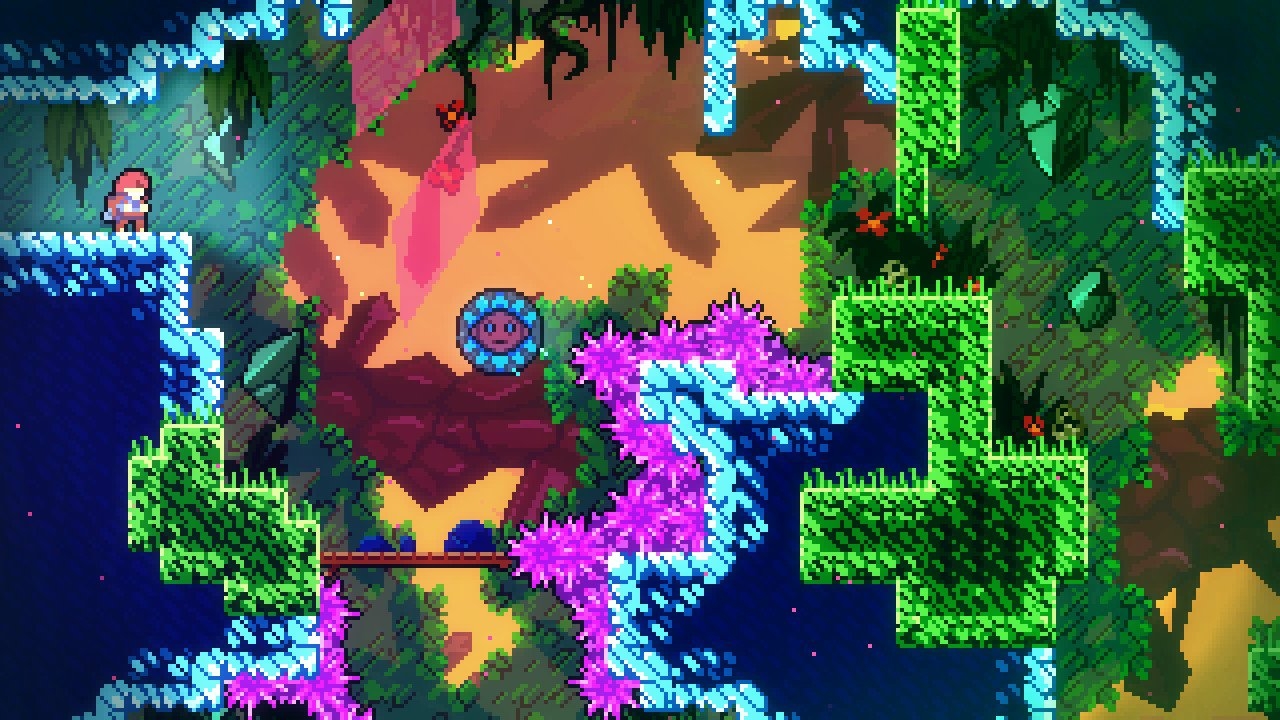

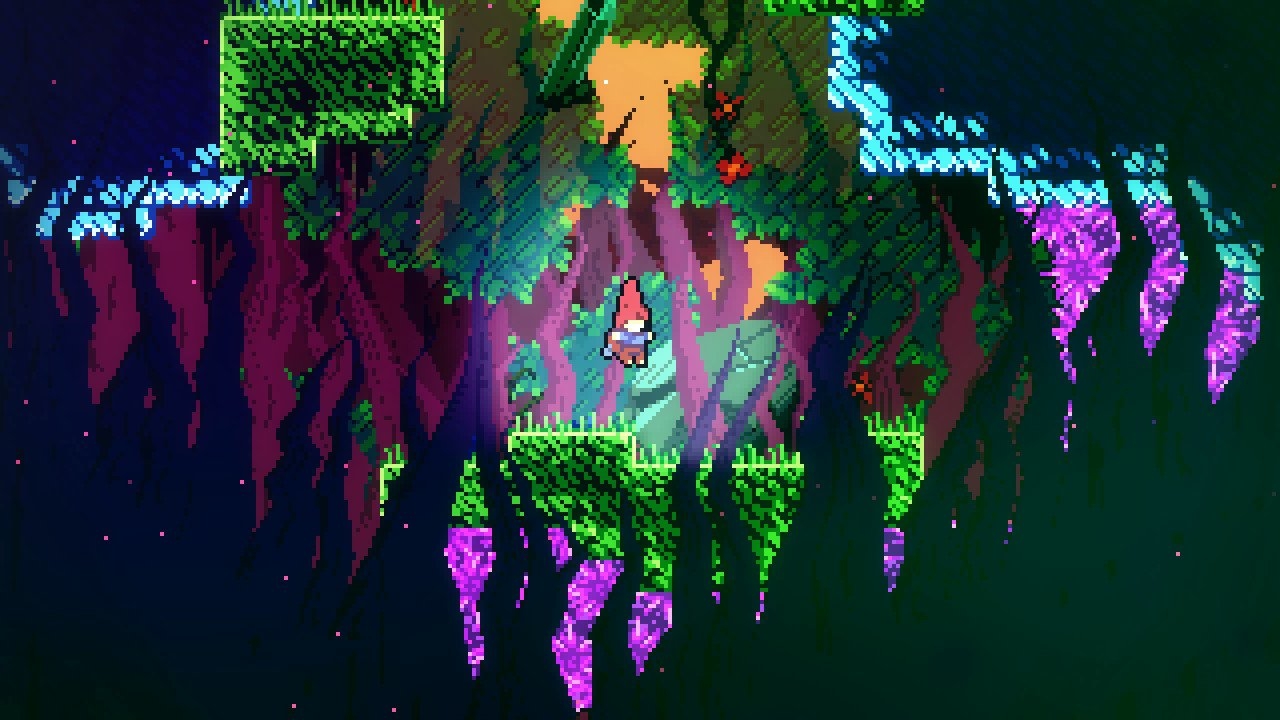

Celeste, a platformer by Matt Makes Games (known for 2013’s Towerfall), is more than just a great side-scroller that takes clear inspiration from Metroid and Donkey Kong Country; it’s a personal odyssey in which the greatest obstacle is one’s own fears and anxieties. Madeline, the protagonist of this brief but powerful adventure, is a young woman who seeks to reach the summit of the fictional Celeste Mountain for no other reason than that she feels the need to overcome her fears, nerves, and depression. Throughout a series of incredible challenges and demoralizing setbacks, Madeline manages to press on in her quest, despite the discouragement of the darker side of her that constantly tells her she doesn’t have what it takes to climb a mountain, either literally or figuratively.

The gameplay behind this spritely indie title is fairly straightforward. Make it to the end of each world (or “Chapter”) by jumping, climbing, and surviving all the way from one screen to the next. There are a litany of collectibles on the way (most in the form of strawberries in what appears to be an homage to Pac-Man) that usually require a certain level of finesse to obtain. Each chapter presents its own unique additions to gameplay, including certain enemies you have to avoid or surfaces that kill you upon impact.

Let me harp on that element of Celeste for a bit: you are going to die A LOT in this game. The first few stages are fairly simple, but the game gets tougher and tougher with every frame. I’m not sure I ever made it through a sequence after the first third of the game without dying at least once. There is no life limit or permadeath or anything, so whenever you die you just reappear at the start of the sequence. In addition, the game counts how many times you die in each chapter and lets you know how many total failures you endured at the end of the main story (my count was 995).

In a handful of cases, the hazards and puzzles are more annoying than riveting. For example, there is a particularly vexing sequence just after the midway point where you have to carry someone through some particularly daunting obstacles, all while being attacked by enemies you can’t kill. While this is just a specific example, these kinds of instances do exist elsewhere in the game, where the difficulty feels more cruel than clever.

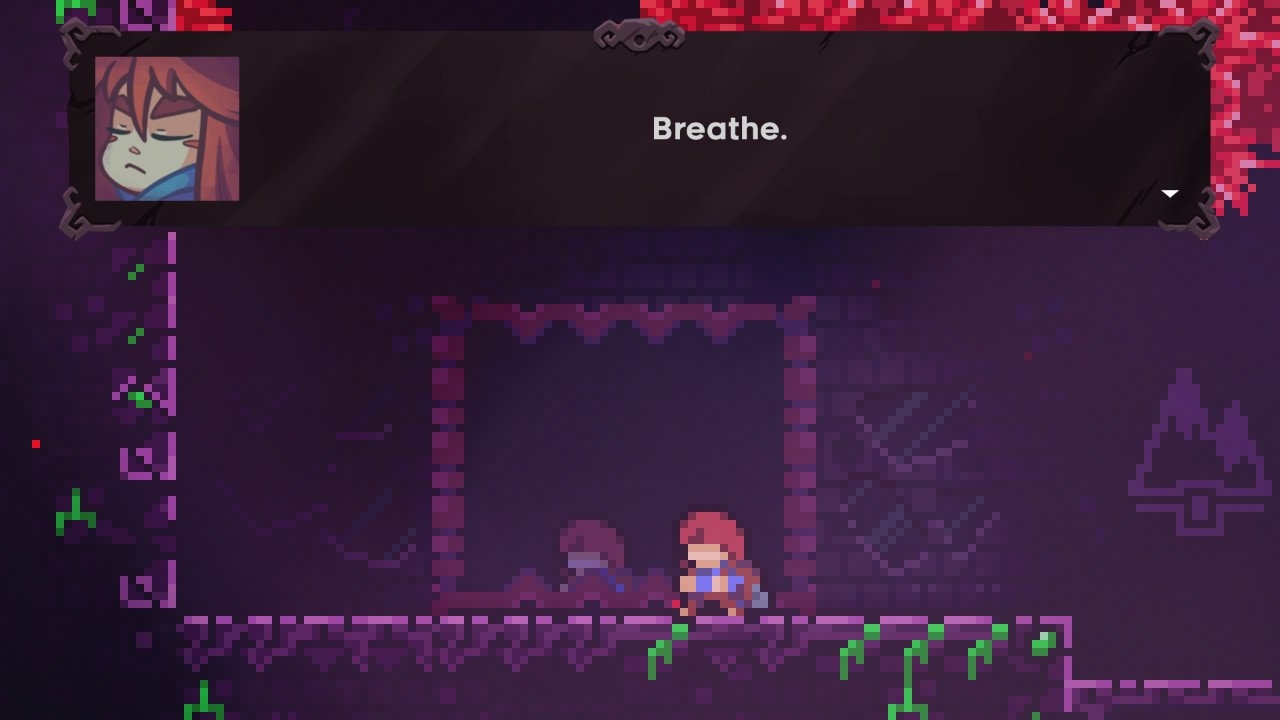

Dying over and over can be frustrating in Celeste, as it would be in anything else, but the game lets you know early on that this is to be expected and that you shouldn’t sweat it too much. After one Chapter, the game tells you that you shouldn’t look at dying in the game as failure, but rather as an opportunity to learn from your mistakes. It may seem a bit patronizing at times, but I appreciated that Matt Makes Games wanted me to feel good about myself, even if I suck.

The main story is fairly short (I beat it in approximately seven hours), but there is plenty of post-game content to satisfy the completionists. While collecting all of the strawberries yields no tangible result (save for a stamp on your save file and a unique story segment I won’t spoil here), it can be a nice challenge for those aiming to extract as much value from Celeste as possible. In addition, each world has an unlockable “B-Side,” or rather its own brutally challenging alternate world. Completing all of these B-Sides then unlocks C-Sides levels, each full of their own unique difficulties. Beyond that, there are even more hidden collectibles to collect, an epilogue level to unlock, and various “full clear” speedruns to complete. Much like its side-scrolling ancestors, Celeste understands that players are always seeking the next challenge beyond the main story.

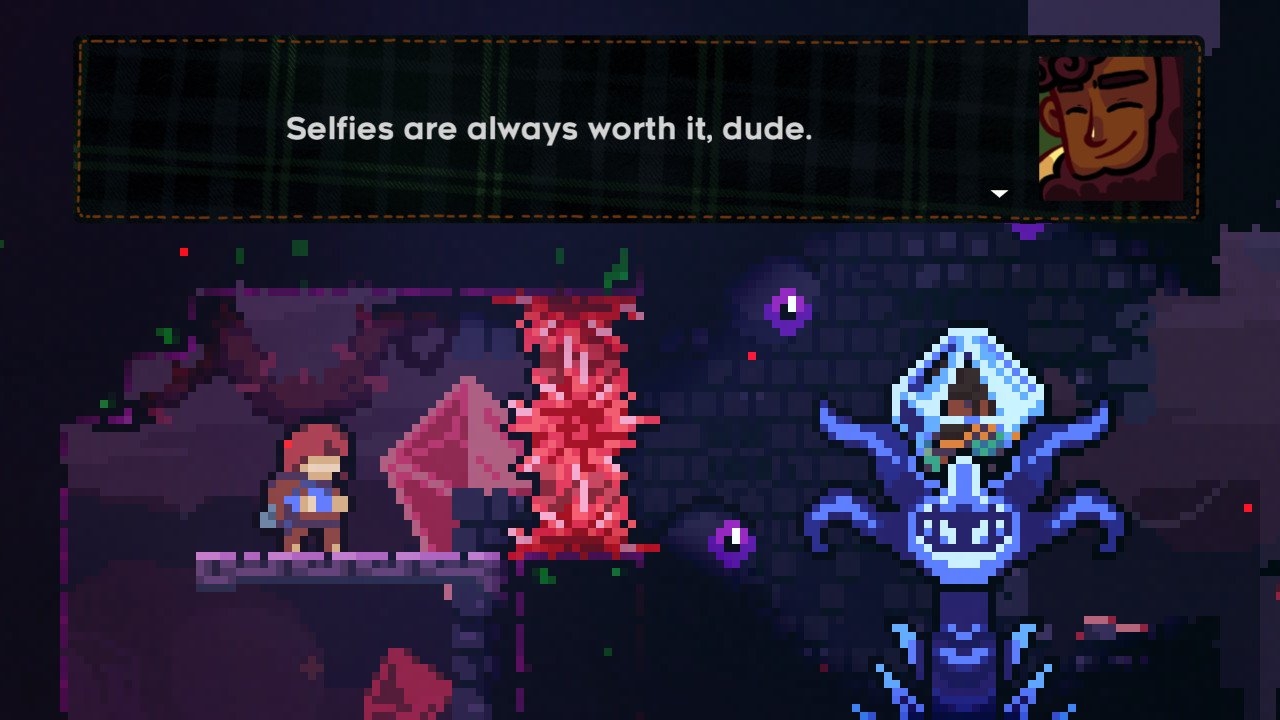

“Selfies are always worth it.”

Despite some frustrating moments, Celeste is an incredibly enjoyable experience, with colorful visuals, a wonderful soundtrack, and clever level design. All that said, what makes it special is its story, its approach to character development, and its intriguing take on mental health. There are plenty of video games with an interesting take on the 2D platforming genre, but Celeste’s story and characters brought a certain charm and sentiment that made climbing that mountain just as essential to me as it was to the little sprite I controlled.

Celeste’s story navigates through many of the stages and properties of anxiety and depression, and as someone who suffers from both, I was amazed at how much Madeline’s character resonated with me. She suffers from panic attacks, frequently doubts herself, and struggles at times to express herself. She feels the weight of the world on her shoulders, even if nobody puts the weight on but her. For her, climbing the mountain isn’t just a great personal achievement; it’s a way for her to have some power over herself, when too frequently she feels powerless.

The characters you meet along the way are kooky but lovable, with each interaction and conversation adding both gravity and levity to an already compelling (albeit largely simple) narrative. One character in particular, Theo, in many ways represents the person Madeline wishes she could be: jocular, easy-going, and willing to take risks. Each interaction they have together is beautifully written, with both travelers willing to reveal their vulnerabilities to one another.

The most intense interactions in the game happen between Madeline and the physical manifestation of her anxiety, which she simply refers to as “Part of Me.” This personification, which serves as the game’s primary antagonist, conveys the internal struggles one may have with their own anxiety, as the protagonist suffers from this apparition’s constant harassment, particularly when she experiences some sort of setback. Madeline must confront her “Part of Me” multiple times throughout the game, sometimes running from it and other times attacking it, but mostly just trying to power through its discouragement.

(some late-game spoilers ahead; skip the next paragraph to avoid them)

Madeline’s relationship with this part of her is especially intriguing and mirrors many of the struggles I’ve had with anxiety. Throughout much of the game, her darker side does not stop telling her to quit, until eventually Madeline decides to just leave that part of her behind… until reconciling with her later to become extra confident (she also gains a powerful new gameplay ability from this reconciliation). I found this both frustrating and partially accurate at the same time. I didn’t like that the game depicted anxiety as something you can throw away or accept at your leisure, but I appreciate that it explained how one way to deal with anxiety is to (up to a certain point) accept its existence and learn to live with it, not necessarily in spite of it. Anxiety is a part of Madeline wherever she goes, and it’s better for her to work with it instead of just pretend it isn’t there. Unfortunately, Celeste makes it seem sometimes as though conquering your inner demons is the same as ignoring them, which is just not true.

(spoilers over)

Still, I appreciate it when developers such as Matt Makes Games try to address the nuances of mental health issues and I admire most of the ways the studio handled Madeline’s anxiety (one scene describes a phone call Madeline has with her mother that was particularly well done). While the use of Madeline’s “evil half” missed the mark in a handful of ways, it was still magical to see Madeline conquer her anxiety without relinquishing a fundamental part of herself. Sometimes, I wish I could fight (and reconcile) with my anxiety in the same way.

Final Thoughts

Celeste’s use of metaphor may be a little on the nose (mountains are frequently used in media to describe great personal obstacles), but that doesn’t mean it isn’t still powerful. Madeline’s odyssey in Celeste is peppered with trials and tribulations, but the way she gets through them is not just through heroic bravery. She still has panic attacks. She still feels the need to take a moment to breathe. She still doubts herself at many turns. How does she overcome? She just keeps jumping and climbing. Sometimes in life, that’s the bravest thing you can do.

All things considered, my favorite part of Celeste was how honest it felt. I truly believed Madeline was scared to climb the mountain, I truly believed that she was her own worst enemy, and I truly believed that she felt the need to achieve something just to prove that she was more than yet another depressed young woman. The game may be full of surprises, but the vast majority of them are in good faith; Celeste wants you to know the hurdles ahead and that you’re more than capable of besting them. The game wants you to know you can get through it, too.

It is fairly refreshing to play a game that wants you to succeed. Any hindrance in your way is presented as a teachable moment, a bump in the road on the way to success. The daunting obstacles of Celeste’s level design (along with its breathtaking soundtrack and art style) are meant to intimidate even the most adept gamers, yet the game knows you can get through it. Hopefully, you know you can, too.

Score: 9.3/10

Sam has been playing video games since his earliest years and has been writing about them since 2016. He’s a big fan of Nintendo games and complaining about The Last of Us Part II. You either agree wholeheartedly with his opinions or despise them. There is no in between.

A lifelong New Yorker, Sam views gaming as far more than a silly little pastime, and hopes though critical analysis and in-depth reviews to better understand the medium's artistic merit.

Twitter: @sam_martinelli.