Welcome to Punished Notes, a series of articles outlining many of my random thoughts on games I’ve been playing, reading about, or even watching on YouTube or Twitch. This week, I examine the Zelda-like qualities of Okami, the uselessness of modern video game lingo, and why sometimes games are better off being short. Plus, FOOTBAAAALLLLLLLLLL!!!!!!!!!!!11111!!!!11!1!1!!

Okami is the Only Zelda-Like that Feels like Zelda

Many games have attempted to emulate the formula behind most Legend of Zelda games, but so many fail to capture the essence of why the series is so beloved. Sure, titles such as Oceanhorn, Darksiders, and Anodyne may appear similar to many Zelda games in terms of basic gameplay and level design, but they don’t embrace the wondrous and emotional qualities that have defined Nintendo’s greatest franchise. Playing those games expecting an experience like Zelda is like ordering a steak au poivre only to receive a slightly overcooked and under-seasoned slab of beef: the two are fundamentally similar, but by no means do they both taste the same.

Okami, however, actually manages to achieve the lofty goal of mimicking several of the best parts of the classic Zelda rubric. Instead of making a game with basic swordplay and environmental puzzles, Capcom released a gem in 2006 (which I am playing for the first time on Switch) that focuses on whimsical environments, colorful characters, and clever world design. Much like Zelda, Okami stars a silent protagonist whose sole purpose in life is to restore beauty and lusciousness to the world, whether by banishing meddlesome demons to the shadow realm, doing favors for happy townsfolk, or even feeding various forest critters. While Link’s quests usually involve saving a princess or a kingdom, his purpose is largely the same as that of Okami protagonist Amaterasu: to bring life and purpose back to the communities of Hyrule (or Termina, Skyloft, etc.) and do what he can to make everyone’s days better. Amaterasu, much like Link, exists purely as an emblem of benevolence.

Each character you meet in Okami has their own little story, ranging from a child who wants to play pranks on his mother to an old man excited to show you his legendary dance moves. While most of these interactions serve the purpose of giving the player more quests and maybe a little more story exposition, they add dashes of brightness and depth to an already colorful world. The player learns to care about the well-being of these people, not in spite of their overall silliness and adherence to cartoonish tropes, but precisely because of these qualities. Nobody has the moral complexity of, say, the average Witcher 3 quest-giver, but every NPC you meet conjures some level of emotional resonance.

My favorite moment from Okami so far (I’ve played about 12 hours) occurs relatively early in the game, during which an old man named Mr. Orange attempts to perform his signature dance that he believes will restore bloom and beauty to his village’s sacred tree. Obviously the player assists with this endeavor, using the celestial brush to actually do what Mr. Orange believes he is doing:

The scene, in all its joviality and levity, rekindled a memory of one of the best parts of my favorite game ever:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dmARqH4qrls

In both scenes, the player engages solemnly with a colorful character and helps him through the power of art. Both may seem like silly, forgettable sequences in otherwise epic games, but they are both emblematic of an essential quality of heroism, namely that almost every person is worth helping, even in unconventional ways.

Moments like these are what drove me to take games seriously as an art form (and write about them, as I do now). No series has given me more of these snapshots than Zelda, and thankfully Okami provides them as well. Instead of strictly adhering to the limiting shackles of nostalgia, Okami does enough to stand out as its own unique adventure that learned the right lessons from Zelda.

Okami is definitely not as good as most Zelda games. The combat is far too easy, the game holds the player’s hand too much (Issun, the Navi-like companion of the story, basically tells you everything you need to know without you asking), and the world lacks the same kind of large, mysterious dungeons that define the Zelda franchise. Still, the game captures the joyful, altruistic essence of Zelda in ways many other imitators have failed, and because of that it is the most successful Zelda-like I’ve played.

Words Matter

The language around videogames is constantly evolving, but I fear that so many of us fall into the same pitfalls when describing certain games. In an effort to explain a new game quickly instead of thoroughly, people often reach for the same set of boilerplate terms that lose meaning each time they’re used. It’s getting to the point where these monikers tell me little about the games they’re meant to describe.

For example, indie developer Sabotage Studio released a new game recently called The Messenger, which has been described in so many ways that I honestly am not 100% sure what to expect out of the game. It looks like classic ninja games like Ninja Gaiden and Shinobi, yet has been described as a Metroidvania with retro-style gameplay and graphics. In another recent example, Polygon described critical darling Dead Cells as “the Castlevania of Spelunkies.” Obviously, these descriptions are meant to be short and punchy for effect, but all they do is further obfuscate what exactly these games are.

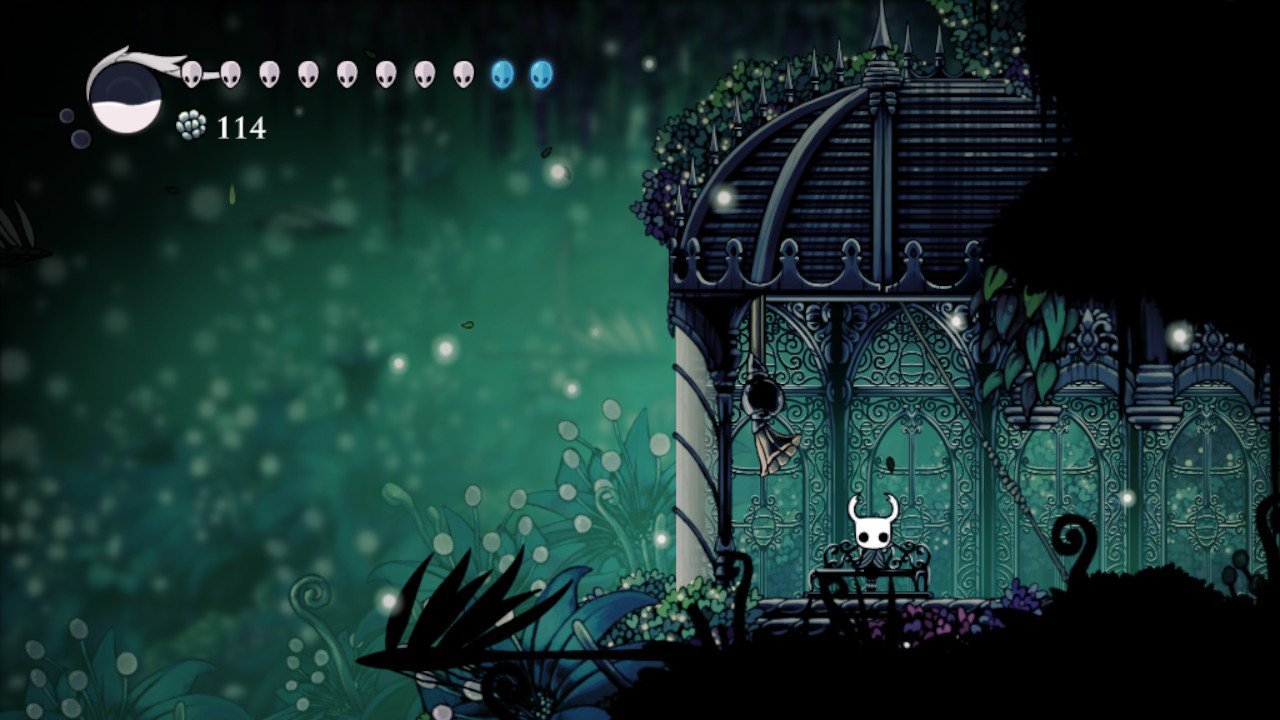

To focus on one example, let’s unpack the term “Metroidvania” for a minute: gamers generally understand what critics mean when they call something a Metroidvania (namely, a non-linear platformer where the player gains abilities later that can be used in areas found earlier in the game), but what happens when you dig a little deeper? Surely Super Castlevania IV should fit that mold, except it’s a completely linear game with clear level progression. Hollow Knight fits that description as well, yet its complex lore and more nuanced world architecture separate it so much from Castlevania and Metroid that the word doesn’t feel accurate. Metroidvania may sound like a helpful term, but only if you assume all non-linear platformers are all fairly similar (they are not), which basically means you must think Hollow Knight and Dead Cells are functionally the same (they are not).

This is obviously just one annoying example, but there are dozens of others that frustrate me all the same: rogue-like (and rogue-lite), JRPG, cRPG, open world, survival, 4X, stealth, etc. These are words that might describe certain mechanics and features of a game, but not really anything beyond that. It’s fine to use some of these terms as a starting point, but everyone need to do a better job of explaining why a game might stand out, not why it’s just like something else.

(Note: I know I focused on Metroidvanias here, but “open world” might be the most eternally frustrating term due to how often it’s used irresponsibly. Some people act as though Grand Theft Auto III was the first ever game to utilize an open world.)

Some Games are Better Off Being Short

I recently completed The Banner Saga 3, capping off one of my favorite franchises of the decade in explosive, heart-pounding fashion. Overall, the game might be the worst in the series overall, but has an excellent final three hours that rival the ending of any game I’ve played over the last few years. I also beat the entire game in under eight hours.

Gamers often debate the value of each title as it pertains to a game’s cost relative to how much they paid for it. This premise is fundamentally flawed, as most wouldn’t feel like they should pay less for a two hour movie than one that lasts three hours, nor does anyone feel like an 800-page novel has more inherent artistic value than a 300-page novel. Part of this is the strange consumer-corporation relationship in the gaming world, where players often feel that game publishers “owe” them more than film studios or book publishers. Another part is that video games typically demand more time from players, with games like Skyrim and Breath of the Wild standing as 100+ hour experiences. Meanwhile, some gamers eschew purchasing shorter, more focused titles like Wolfenstein II: The New Colossus at full price since, in theory, they only provide a fraction of the “value” of a longer game.

To all this, I say “Phooey!” (Yeah, I said it.)

I understand why some people might feel cheated if they paid $60 for a game they can complete in under a week, but most longer games that provide more “value” often just provide more fluff. Does adding more hours automatically make the experience better? Sure, you can sink hundreds of hours into, say, Skyrim, but how many of those hours were actually meaningful? Meanwhile, the ten hours I logged in Wolfenstein II were chock-full of action, emotional swings, and some of my favorite gaming moments of 2017. Would the game have felt better if they added 15 more hours of fetch quests or a million more collectibles?

Games don’t necessarily have to be long in order to be good. Some games respectfully earn the right to demand dozens of hours of gameplay (e.g. Breath of the Wild, The Witcher 3, Fallout 3), but most single player games don’t have more than 20-25 hours of truly good content. Why add more for no reason?

Your hard-earned money is certainly valuable, but so is your time, the only resource you can never get back. Think about that whenever debating your next game purchase.

LIGHTNING ROUND!!!!!

-A quick message for gamers who harass reviewers that examine and thoughtfully critique the political and social implications of video games: YOU CAN’T DEMAND PEOPLE TAKE THIS PASTIME SERIOUSLY AND SIMULTANEOUSLY RAIL ON CRITICS WHO DO EXACTLY THAT. You can’t have it both ways, people. (Also, don’t care for the sociopolitical leanings of several writers at Waypoint and Kotaku? GO SOMEWHERE ELSE FOR YOUR SHITTY “IS IT GOOD?” GAME REVIEWS.)

-Staying on the subject of video game reviews: as much as we have fun here at TPB with Metacritic reviews, I just wish sometimes that people wouldn’t take the numbers themselves at face value. There’s virtually no reasonable way to compare Shadow of the Tomb Raider to NBA 2K19, so whatever scores each one gets should be inconsequential to one’s purchasing decisions. Just READ the damn reviews, people.

-Pretty much every game in existence has a photo mode now, but I still feel like the feature was always meant for No Man’s Sky. Love it or hate it, the game pretty much always looks good.

-I love the new direction 2K Sports is taking with the new MyPlayer mode of NBA 2K19 (based on what I’ve played from the Prelude demo). Instead of playing a few college games and then getting drafted by an NBA team, the player you create gets passed on at the draft and has to work his way through playing in China and the G-League (essentially the NBA’s minor league) before making it to the Association. It’s a welcome new direction for the franchise, and one that might warrant a purchase.

-As I was watching the New York Giants’ inaugural game of the 2018 NFL season, I found myself in an unusual malaise. I was noticeably lethargic, my breath smelled awful, and I just overall felt like a piece of garbage. It then occurred to me that the only sustenance I’d consumed over the prior two hours was beer, chips, cocktail peanuts, and a burger with tons of ketchup. My team ended up losing in a particularly dumb and avoidable manner, leaving me simultaneously angry and hopeless. Welcome back, football!

Sam has been playing video games since his earliest years and has been writing about them since 2016. He’s a big fan of Nintendo games and complaining about The Last of Us Part II. You either agree wholeheartedly with his opinions or despise them. There is no in between.

A lifelong New Yorker, Sam views gaming as far more than a silly little pastime, and hopes though critical analysis and in-depth reviews to better understand the medium's artistic merit.

Twitter: @sam_martinelli.